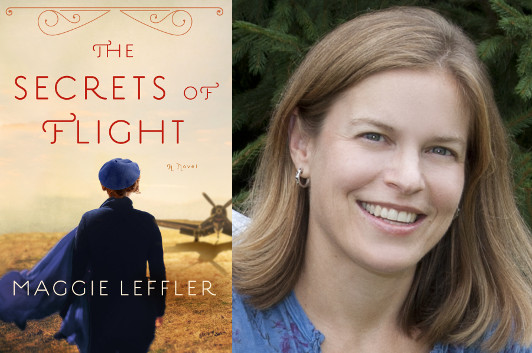

Maggie Leffler’s Long Path to Flight

photo: Hills Studio

I first got to know Maggie Leffler just over nine years ago, when her debut novel, The Diagnosis of Love, came out. Now I’m reading her third book, The Secrets of Flight, and I’m hooked by its interlocking stories about two young women trying to figure out who they want to be… and how to become it—but also, as you’ll see, what happens years later, after the choices you’ve made and the circumstances you can’t control. Now, one of the reasons it’s been so long since a follow-up to Leffler’s first two books is that she has a full-on career as a family physician, but as you’ll learn in this guest essay, it also took her longer than she’d anticipated to find the right shape for this particular narrative. She did, though, and that’s great news for us.

Madeleine L’Engle once wrote, “I think that all artists, regardless of degree of talent, are a painful, paradoxical combination of certainty and uncertainty, of arrogance and humility… and yet with a stubborn streak of faith in their own validity no matter what.” Over the last six years of writing my third novel, these words have never felt truer.

In 2009, after reading about President Obama honoring World War II’s forgotten “fly girls” with Congressional Gold medals, I set out to write a family saga from four points of view, including that of a Women Airforce Service pilot (WASP). After it was completed in 2012, my agent sent The Secrets of Flight out to a round of rejections. The manuscript was overstuffed with characters, and, to boot, one of them, Jane, was unlikable (poor Jane!). Two drafts later, after the novel went out again—sans Jane—to be met with more rejections, I was in despair, yet compelled to keep writing all the same. Sometimes it’s not conviction urging me onward, but the story itself that needs to come out before I’m consumed.

That same summer, I confessed to my husband a secret dream of mine since the age of fourteen: I wanted to make a film, but I was scared to learn how. What if my attempts were awful? He pushed me to take a class at Pittsburgh Filmmakers, which gave me a different perspective for the book—or at least a healthy break from it. With each passing year, it became easier to kill another darling.

Soon the novel belonged to the two main characters I’d conjured up in the very beginning: Mary, the former WWII pilot with a secret, and Elyse, the big-hearted teen who would save her. Another distinct point of view also emerged, that of the young pilot’s… except that I had no idea what it felt like to have flown planes during the war. Finding the answers led to a friendship with Florence Shutsy-Reynolds, a Women Airforce Service pilot who inspired me with her stories. Finally, in 2014, the novel was ready for another round.

8 May 2016 | guest authors |

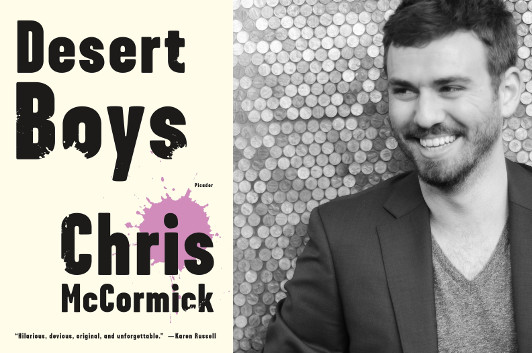

Chris McCormick & the Management of Grief

photo: Jenna Meacham

“The Antelope Valley is not the California most people imagine,” Chris McCormick writes. “This could be a good thing, but almost never is. The stories in McCormick’s debut collection, Desert Boys, are centered around Daley Kushner, a young man who grew up in Antelope Valley, left to go to school in Berkeley, and became a writer—much like McCormick himself. How much like, I wouldn’t know, but I can tell you that stories like “Mother, Godfather, Baby, Priest” and “You’re Always a Child When People Talk About Your Future” give a strong sense of what it must have been like to come of age as a gay, half-Armenian teenager in the desert north of Los Angeles in the years just after 9/11, and finding your way toward an adult identity as a twentysomething today.

I guess one reason for stories is the management of grief. The grief in question can be shared or private, but sometimes, fluttering between worlds, it can be both. Like a spirit, or—more interesting to me—like any regular person torn between an old home and a new home, or between belonging to a community and relying on an idea of selfhood, or between the raucousness of an inner life and the contrived but more palatable version we present to others. These conflicts, I think, are some of the prices we pay for freedom, and they only get more tangled and impossible to parse when grief, the fluttering kind, is involved.

Shaila Bhave, the narrator of Bharati Mukherjee’s “The Management of Grief,” has just lost her husband and sons to the terrorist bombing of Air India Flight 182. The plane—from Canada to Delhi through the UK—has exploded over Irish waters, killing the 329 people onboard, most of whom were Canadian-Indians visiting the country, and the family, they’d left behind.

Shaila—just one of hundreds in her community whose family has been ruptured by the attack—quickly garners a reputation as “a pillar,” somebody who has taken the tragedy “more calmly” than the others. But what others see as strength, Shaila understands to be a deep flaw: “This terrible calm will not go away.”

7 May 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.