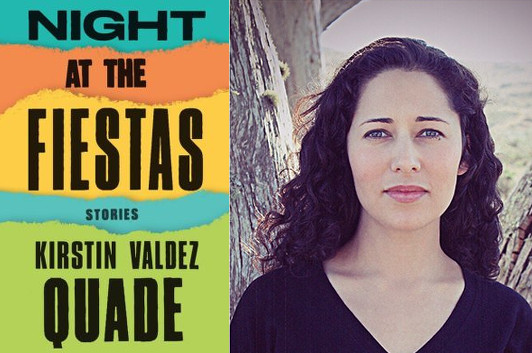

Kirstin Valdez Quade on “Parker’s Back”

photo: Maggie Shipstead

“One of the themes I find myself returning to again and again in my fiction is faith,” Kirstin Valdez Quade says at the beginning of this guest post; indeed, one of the first things you’ll notice as you read the stories in Night at the Fiestas is the strong presence of religion, and religious pageantry, in her characters’ lives. So it’s not unexpected that she might turn to Flannery O’Connor when asked about the short story writers who’ve been an influence or inspiration to her—but it’s a delightful surprise to see that she’s singled out one of my favorite O’Connor stories to discuss.

One of the themes I find myself returning to again and again in my fiction is faith. As a child, I spent a lot of time with my very devout grandmother and great-grandmother, and I went to mass regularly. Northern New Mexico Catholicism is full of petitions and processions, home altars and lit candles and plaster saints on the mantle. It’s also the Catholicism of agonized depictions of Christ, His wounds gaping and bloody.

The Catholicism in Flannery O’Connor’s fiction is similarly gory. She specializes in petty, flawed characters, characters who nonetheless are drawn to transcend themselves. When they’re lucky, these characters, however unpleasant and undeserving they might be, are granted grace—though usually when grace comes, it’s violent and at the last minute. My favorite O’Connor story is perhaps “Parker’s Back,” one of the two pieces she was working on when she died. I love the story for its occasionally cruel humor, but also for its depiction of a faith that is ugly, uncomfortable, and deeply necessary.

O.E. Parker is a flawed man. He lives wildly, selfishly, likes his drink and likes his women. Parker repeatedly runs away from what he most needs—to be truly seen, by himself and by God. He can’t even bear to admit to his full name (Obadiah Elihue! Who could bear it?).

Yet Parker longs to transform himself and transcend himself. He covers himself from head to toe in tattoos, always seeking “a single intricate design of brilliant color…an arabesque.” Still, every tattoo disappoints, and that unity of self eludes him. His anxiety only increases, until there is only one place left uncovered: his back.

Inevitably, “dissatisfaction began to grow so great in Parker that there was no containing it outside of a tattoo,” and he takes off once again for the city, in search of the tattoo that will unify him.

Flipping through the pages of the tattoo artist’s designs, he comes upon an image that stops him in his tracks: “the haloed head of a flat stern Byzantine Christ will all-demanding eyes.” Theologian Paul Tillich writes about the “fascinating and shaking character of the holy,” the way that man is both drawn to the infinity of God and also repelled and terrified by God’s enormity. In this moment, Parker understands this concept viscerally; he is horrified by the image, yet he needs it tattooed on his back.

I’m interested in the contradictions in O’Connor’s depiction of Parker’s faith. He’s not a good person, yet he’s granted grace. In O’Connor’s fiction it’s never the pious or the do-gooders or the self-satisfied who find self-knowledge or grace or closeness to God. Certainly Parker’s humorless wife, with her uncompromising Protestant joylessness, isn’t granted anything at all, except a husband who’s a total liability. What sets Parker apart is his longing for transformation. And longing—with all its messiness and indignity—is the lifeblood of fiction.

15 February 2015 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.