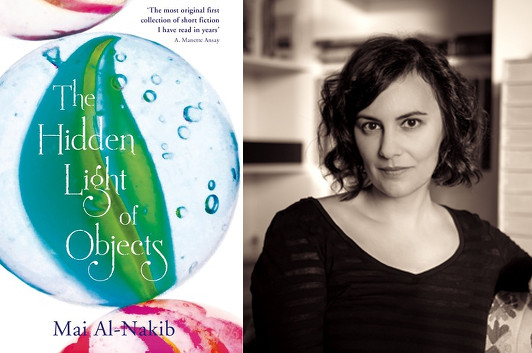

Mai Al-Nakib Looks at Men in the Sun

photo: Omar Nakib

One of the persistent themes in Mai Al-Nakib’s short story collection, The Hidden Light of Objects, is the way that we use stories to shape our own lives and identities, a common thread across decades and borders. Though her stories are not fantasies, there’s a slight trace of the surreal to them, especially early on, as if naturalism were given the tiniest of nudges. In this guest essay, Al-Nakib tells us about another Middle Eastern writer whose visionary prose has helped shape her own.

Ghassan Kanafani was an artist before he was a writer. This shows in his writing, which privileges vision above all the other senses.

I came to Kanafani late. I was a graduate student when I first read Men in the Sun. The sparseness of his language struck me, but I didn’t really notice the visual aspect of his style. Perhaps it’s because I was busy reading for content, overwhelmed by the political weight of his words. I remember the heat of a strange guilt rising up my neck as I learned that the three Palestinian men, who would die together in an overheated water tank, were desperate to be smuggled across the desert into Kuwait. Kuwait—that’s where I’m from. It turned my mouth sour to read those famous last lines of the story, “Why didn’t you knock on the sides of the tank? Why didn’t you bang the sides of the tank? Why? Why? Why?” The first time I read Men in the Sun—a short novella or, as I prefer to think of it, a long short story—I was busy feeling the anguish Kanafani no doubt wanted his readers to feel, anguish over a lost cause, over wasted, wretched lives, over betrayal and corruption and injustice. In the depths of that anguish, however, I overlooked what I now see as Kanafani’s characteristic visual aesthetic.

Let me give you an example. In a scene in the second chapter, one of the three men who will die in the sun, Assad, is negotiating with a smuggler who folds yellow papers as he “look[s] up at him from under his heavy eyelids.” Those yellow papers seem innocuous and we pass over them quickly, reading on to learn whether Assad will fall into the trap of this lizard-eyed man. But the narrative slips from the present scene into Assad’s recent experience with another cheating smuggler, who had tricked him into trekking across the desert into Baghdad on foot, when he had initially promised to take him there by lorry. The yellow papers transform into “yellow slopes” of desert:

“He crossed hard patches of brown rocks like splinters, climbed low hills with flattened tops of soft yellow earth like flour. […] The horizon was a collection of straight, orange lines, but he had taken a firm decision to go forward, doggedly. Even when the earth turned into shining sheets of yellow paper he did not slow down.”

But the yellow does not stop with this recollection of the recent past. Assad is thrust forward into the present when “[s]uddenly the yellow sheets began to fly about, and he stooped to gather them up.” A fan has scattered the heavy-lidded smuggler’s yellow papers, slices of the desert Assad must inevitably stoop to navigate, despite the dangers of which he is well aware.

Kanafani uses color here to slip present into past and back again. He uses it to scramble our sense of time. Elsewhere in Men in the Sun, he uses similar visual cues to bleed characters together, so that names—Assad, Abu Qais, Marwan—are no longer sufficient markers of identity. In their struggle to escape occupation, to carve out better lives for themselves and their families, to get to the promised land of Kuwait, and, finally, even in death—they are one. In addition to the yellow desert, the image of an indifferent, black road recurs throughout the story, as does that of the sun, “a broad dome of white flame over the desert.” These striking, recurring pictures shape the story, help produce its layered, overlapping structure. Through that intricately woven form, the anguish of the content is intensified. I don’t think I could see this when I first read Kanafani, all those years ago.

I came to Kanafani’s short stories rather late, as I’ve said. I came to his visual verbal aesthetic even later. Kanafani the artist writer has taught me how effective it can be to tangle up the senses, to confound our expectations about language. The best ekphrastic writing does this, reminds us that writing was image first. In my own writing, the visual resonance of language is central. When I read Kanafani now, I understand why.

9 February 2015 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.