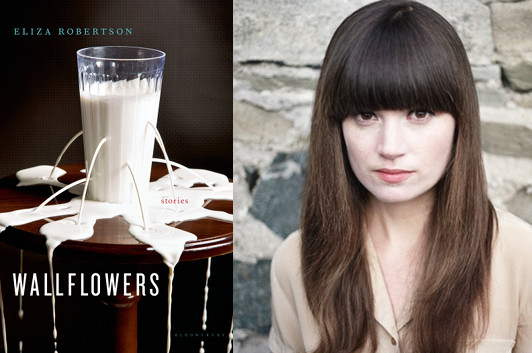

Eliza Robertson: A Voice Beyond Words

photo: via Bloomsbury

As I’m reading through Eliza Robertson’s debut collection, Wallflowers, the stories that stand out in my memory are often those where the characters find themselves grappling with profound emotional losses, like the young narrator of “Ship’s Log,” whose attempts to dig a hole to China from his grandparents’ yard in Ontario barely overly his grief and fear at his grandfather’s death, or the narrator of “My Sister Sang,” listening to the black boxes from crashed airplanes, or Natalie, the protagonist of “Where have you fallen, have you fallen?” whose story is told in reverse chronological order.

These stories, and others in the collection, show Robertson’s formal playfulness to strong effect. In this essay, she discusses how Jonathan Safran Foer pushes language even further—beyond the written word, even—to arrive at the right way of hitting his story’s emotional register.

My PhD subject is prose rhythm. I’ll spare readers the gory details, but rhythm has led me to think about voice—how we use that word so often we have forgotten it’s a metaphor. “Voice of a generation.” “New voice.” “A voice piece.” (Which often translates to: the characters talk funny.) From here, if you will follow me down the wormhole, I started to think about how the term “voice” is premised on utterance. Don’t get me wrong: I talk about voice in fiction too. I will continue to talk about voice. But I wanted another word that included silence, whitespace and punctuation. Enter rhythm. Enter also “A Primer for the Punctuation of Heart Disease” by Jonathan Safran Foer.

The title summarizes the story very well. It is a primer for the silences and emphases (read: punctuation) organic to the narrator’s family communication on love, the holocaust, and yes, heart disease. The sentiment emoted by these symbols is so much more urgent—even vital—than what could be relayed by words. That is: the symbols undercut, footnote and italicize what is spoken.

For example, in the following passage, the silence mark, â–¡, represents an absence of language, and â– , the “willed silence mark,” represents an intentional silence— often employed in response to questions you don’t want to answer. As seen here:

The “insistent question mark” denotes one family member’s refusal to yield to a willed silence, as in this conversation with my mother.

“Are you dating at all?”

“â–¡”

“But you’re seeing people, I’m sure. Right?”

“â–¡”

“I don’t get it. Are you ashamed of the girl? Are you ashamed of me?”

“â– ”

“??”

12 October 2014 | selling shorts |

Helen Marshall’s Two Short Story Mentors

photo: via ChiZine

Gifts for the One Who Comes After, the second collection by Canadian author Helen Marshall, is full of dark, unsettling stories. Not horror, precisely, although they’re certainly unworldly, in a way that enables certain moments to take up residence inside your head long after you’ve set the book aside. Heck, “All My Love, A Fishhook isn’t even a particularly supernatural story, or at least you can read it that way, and it’s still disturbing…

As I was reading, I was reminded of some of the episodes from the original Twilight Zone, ones like “It’s a Good Life” or “Nothing in the Dark,” though with greater subtlety. (Look, I love “It’s a Good Life” as much as anyone, but subtle it ain’t.) In this guest post, Marshall tells us about two writers who’ve helped shape her voice—one of whom I’ve already read with great pleasure, which inclines me to track the other down at the first opportunity.

There are stories that, the first time you read them, are so gorgeous, so powerful, and so magical that they remind you that fiction exists for the sole purpose of learning what you can get away with. There are two such experiences that have been etched into my mind. The first was when I picked up Robert Shearman’s collection Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical. The cover is sweetly unassuming: three miniature animal-headed girls in tartan skirts stand clustered on one side while a lone figure, dressed identically, but with a sleekly insectoid face of a fly slumps on the other side. It doesn’t prepare you. Not at all. Inside are a host of darkly comic stories that weave together the surreal and the achingly human. Reading these stories is like hugging a teddy bear only to discover someone has stuffed it full of razorblades. It might feel good at first, but you don’t realize until you’re bleeding out how deeply you’ve been cut.

One of my favourite among the stories is “Pang”—about a middle-aged man who lives in a universe where lovers literally hand each other their hearts in a Tupperware container. Facing the dissolution of his marriage, our hero desperately searches the house for his lover’s heart only to discover he has carelessly misplaced it while she has taken excellent care of his. As we follow his quest to substitute a pig’s heart from the local butcher shop, we come to understand his growing coldness and the possible reasons for the breakdown of their relationship. It’s a beautiful example of a story which blasts past the absurdism to find something touching and real.

Another story which picks up similar themes is “One Last Song,” which follows the trajectory of a young boy’s career as he manages to write one of the world’s greatest love songs—only to find in his later years that he can never quite live up to the early hype. These are stories that make you hurt in the best possible way, and they showed me that there’s a power in charming your audience that can be made devastating in the right hands.

11 October 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.