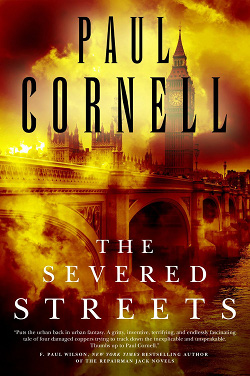

Read This: The Severed Streets

In 2010, China Miéville’s Kraken served up, among many other delightfully weird story elements, a division of the London police that specialized in crimes involving the supernatural world, and in the years since reading that book I’ve noticed a few other books that place the eldritch London police procedural front and center. (Note: I’m not counting Charlie Stross’s “Laundry Files” series, because that’s more about combining supernatural horror with a particularly British type of spy thriller.) I’ve been meaning, for example, to dive into Ben Aaronovitch’s Rivers of London and its sequels for a while now, and I’m doubling down on that intention, now that I’ve recently read the two books in the series that might be its most direct competition.

Paul Cornell’s London Falling introduced readers to the “Shadow Police,” four members of the Metropolitan Police force who, while confronting the prime suspect in the murder of a local crime boss, are inadvertently gifted with “the Sight,” enabling them to see the (generally sinister) magical undercurrents of the City. The experience terrifies them more than a little, but they also recognize that, now that they know there are dark forces at work in their city, their dedication to police work calls on them to do something about it—so they decide to hang on to their newfound abilities and let London’s supernatural underworld know that they’re prepared to lay down the law. And The Severed Streets picks up the story very soon after…

Paul Cornell’s London Falling introduced readers to the “Shadow Police,” four members of the Metropolitan Police force who, while confronting the prime suspect in the murder of a local crime boss, are inadvertently gifted with “the Sight,” enabling them to see the (generally sinister) magical undercurrents of the City. The experience terrifies them more than a little, but they also recognize that, now that they know there are dark forces at work in their city, their dedication to police work calls on them to do something about it—so they decide to hang on to their newfound abilities and let London’s supernatural underworld know that they’re prepared to lay down the law. And The Severed Streets picks up the story very soon after…

Now, it happens that the initial gimmick of The Severed Streets—a series of murders that may possibly have been committed by the ghost of Jack the Ripper—has already been the central premise of Maureen Johnson’s YA paranormal thriller The Name of the Star. But Cornell takes that plot kernel and cultivates a completely different story from it, not least of all because he’s coming at it from the perspective of a native Brit for whom gritty ’70s cop shows like The Sweeney are almost certainly a formative influence, one that’s jokingly acknowledged here and there. Cornell’s novel is very much plugged into the contemporary unrest over economic inequality, and it only takes a bit of prodding on his part to create a fictional London on the brink of civil chaos that (supernatural aspects aside) feels plausible. He’s also very effective at showing how his four main characters cope with the discoveries they’re making as they probe the contours of their new territory. There’s a lot of information for them to process, as well as personal crises to work through—and Cornell manages to keep all these balls in the air while moving forward with nearly consistently effective pacing.

Also, Neil Gaiman shows up for absolutely perfect reasons, managing to make even an extended expository dialogue entertaining… although, by the time he heads offstage, you may never be able to look him in the eye should you ever meet.

29 July 2014 | read this |

Mark Chiusano: A Year of “Moral Disorder”

ohoto: Charlotte Alter

Though the initial stories in Marine Park are focused on a boy and his brother growing up in the far end of Brooklyn, near the park that gives the collection its name, Mark Chiusano has plenty of other characters to introduce us to, like the couple whose romance rises and falls in the shadow of the Manhattan Project, or the chain of people linked by their sexual histories in 1970s New York City, or the old man who’s called upon to make one last smuggling run in the waters just off the outer boroughs. A few of these stories hint at the expansive time frames Chiusano talks about taking on in this essay—which discusses how to fit a great deal of time into a relatively small amount of prose.

For my day job I work at Vintage Books, where I’ve been working recently on a new project called Vintage Shorts, a program that pulls small sections from our old books for timely anniversaries or events in order to introduce readers to books they might have missed. Working on the project has had the side effect of introducing me to plenty of books I’ve missed. Two of them are Margaret Atwood’s story collection Moral Disorder and Geoffrey C. Ward’s biography of FDR, A First-Class Temperament. At the time I’d been trying to train myself in my own writing to lengthen out the time-frame in stories—many of the stories in Marine Park take place over days or hours, and I’d been experimenting with widening that scope. Reading A First-Class Temperament was an ideal way to increase my stamina, as it were.

Ward’s book is one of those fantastic, monumental, expansive and all-encompassing portraits of a historical figure—First-Class gets particularly close to Roosevelt as he struggles with polio, outlining the painstaking details of learning to “walk” again (he never would). Ward himself suffered from polio as a child and the attention to physical detail in his writing is palpable. In one of my favorite chapters from the book, Ward describes the two years in which Roosevelt goes from being a hermetic cripple to a political player once again, bookended on one side by his failed attempt to crutch himself into his old law office, and on the other by his journey down the aisle at the 1924 Democratic Convention to deliver the fabled Happy Warrior speech in support of Al Smith (“happy warrior,” a phrase from Wordsworth, wasn’t FDR’s idea, by the way: he thought it was far too poetic).

The chapter has the arc of a short story, with the repetition of attempts to walk at beginning and end, supported by a middle section in which FDR escapes on his houseboat Laroco for a spring cruise off the coast of Florida, a change of scenery that allows the reader to learn more about Roosevelt’s state of mind at the time (though Roosevelt hid it well from his houseboat guests, he sometimes couldn’t bring himself to leave his bed until noon) before the climactic events of the ending. Simple temporal section-openers like “At around eleven o’clock on Monday morning,” and “In February 1923, Franklin received from an old friend in England an elixir,” or “At around two-thirty in the afternoon of Monday, February 4, the Laroco anchored off St. Augustine,” are the bare-bones of nonfiction, but became useful in my fiction to help stories cover months and years.

28 July 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.