It’s Always Darkest Before It Turns Pitch Black

My wife’s book club had read Herman Koch’s The Dinner when it came out in 2013, so when she saw me headed into the living room with her copy of it a while back, she predicted that I’d read through it in a single sitting—and she wasn’t that far off. (About halfway through, I had to get a glass of water.) For those of you not familiar with the novel, it’s essentially a monologue by Paul Lohman, a retired Dutch schoolteacher who, as the story begins, is out with his wife, on their way to a trendy restaurant where they’ll meet Paul’s older brother, Serge, and his wife, to discuss a situation that affects not only their respective children but Serge’s political aspirations.

Now, Paul is an extremely cagey narrator, and the story unfolds in a series of micro-revelations, so—after a few chapters—I went back to my wife, and I asked her, “This video, it’s going to turn out to be [redacted], right?†Oh, no, she assured me, it’s much worse than that. Much, much worse, it would turn out.

And, sure, some of the power of The Dinner lies in the shocking incident at the heart of the story, but only some. The greater strength of the novel is in Paul’s personality and the way it shifts from the time he and his wife leave for the restaurant to the time he returns home. In the beginning, we’re drawn in by his narration; he may be a bit closed off emotionally, but he’s smart and engaging, perhaps especially in his annoyances at the little pretensions of those around him. We may be able to identify with those frustrations, and consequently find ourselves warming up to him, taking his side against Serge’s before the evening has really begun.

It’s safe to say you’ll come to feel very differently about Paul by the end. As a narrator, Paul reminded me a great deal of Lou Ford, the protagonist of Jim Thompson’s noir classic The Killer Inside Me. I was reading The Dinner in preparation for an interview with Herman Koch, part of the “Word for Word†series at Bryant Park in midtown Manhattan, so when we met before the event, I brought this up. (I didn’t want to spring it on him in front of an audience and then find out maybe he wasn’t familiar with Thompson, after all.) As it turned out, he hadn’t read that novel, but (after The Dinner was written), he had looked up another of Thompson’s books, Pop. 1280, and he could see where people would find the common ground.

(more…)

11 June 2014 | read this |

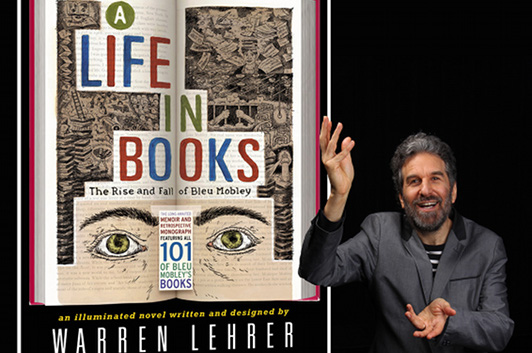

Warren Lehrer & the Bleu Mobley Oeuvre

photo and illustrations via Warren Lehrer

Warren Lehrer’s guest essay stems directly from a question I posed to him when I invited him to write about A Life in Books, a question that tackles the way it addresses the life of a fictional writer not just through that writer’s words, but his book jackets. “What drew you to telling a story through a mosaic of imaginary books?” I wanted to know. This was Lehrer’s response.

(By the way, all the artwork you’ll see below—and much more besides—is also part of a traveling exhibition that has often included a performance/lecture by Lehrer. Something to keep an eye out for…)

My previous five books were all non-fiction: four portrait books about eccentric Americans who each straddle the wobbly line between brilliance and madness, and Crossing the BLVD: Strangers, Neighbors, Aliens in a New America, written with Judith Sloan, which documents 79 new immigrants and refugees from all over the world who live in Queens.

After representing all these real people and their stories, I felt a need to work on something that gave me more room for invention, and allowed me to get at the interior world of characters. I started looking at all these book ideas I had scratched into notebooks, and drawers full of short stories and interior narratives I had written. And somehow, this peculiar, well-meaning if ethically challenged writer character emerged—Bleu Mobley—who was presently in prison looking back on his life and career.

Instead of just writing his story, I decided to combine his reluctant memoir with a retrospective monograph of all 101 of his books including their cover designs and ‘first edition’ catalogue copy. But the covers and catalogue descriptions didn’t satisfy my curiosity about my protagonist’s creative output, so I began writing book excerpts (that read like short stories). The excerpts started cluing me into aspects of Mobley’s life (people, scenarios, motivations) that I hadn’t anticipated. Some book titles that I thought came early or late in his career turned out to be middle period works, and vice versa. My Bleu Mobley life events/bibliographic timeline chart kept changing. As the puzzle of Bleu Mobley’s life revealed itself to me piece by piece, the relationship between an artist’s life and his or her work emerged as a major theme.

In the memoir part of A Life In Books, Mobley claims to have never written about himself, yet we discover him and the people he loves sleucing through all his books, however obliquely.

9 June 2014 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.