At Home, at Anfield: Red or Dead

I first started seriously watching soccer with the 2010 World Cup, and when Premier League football started up later that summer, I began watching those games on the weekends. I kept an eye out for players that I’d seen competing in the Cup, but I didn’t form any particular club loyalties until early 2011, when Kenny Dalglish was appointed manager at Liverpool. I’m a sucker for sports history, you see, so even though I had no direct experience of Dalglish’s earlier career playing for and managing Liverpool from the late 1970s to the early ‘90s, the story of his return to Anfield (the team’s home stadium) resonated with me.

(As a rough analogy in American sports terms, imagine Phil Jackson wound up back with the Chicago Bulls—or with the New York Knicks, even.)

So I’d made a mental note about Red or Dead, David Peace’s novel about an even earlier period in Liverpool’s history, when I first heard about it earlier this year. Then I saw a finished copy at the Melville House display booth at BookExpo America, and with another World Cup coming, I moved it a bit higher up my reading list. I’m glad I did, though it’s easily the most challenging book about sports, fiction or nonfiction, that I’ve ever read.

Red or Dead is the story of Bill Shankly’s tenure as manager of Liverpool Football Club from 1959 to 1974, the stuff of legends on a par with Vince Lombardi’s time with Green Bay or Red Auerbach’s career with the Boston Celtics. Possibly even more legendary; I admit that I’m coming to the novel as an outsider, with an understanding of British sports culture that is more intellectual than intuitive, so at some level I have to estimate the emotional resonances.

That said, it’s clear how intently Peace feels those resonances, clear in every sentence he writes. Instead of telling Bill Shankly’s story in conventionally straightforward, almost journalistically observational prose, Peace adopts cadences and rhythms that generate an almost mythic aura, as he traces what feels like every single step of Shankly’s time at Liverpool. For example:

“On Saturday 3 March, 1962, Liverpool Football Club travelled to Fellows Park, Walsall. But Bert Slater did not travel to Fellows Park, Walsall. Bill Shankly had dropped Bert Slater. Bert Slater had played ninety-six consecutive games for Liverpool Football Club. But Bert Slater would never play another game for Liverpool Football Club. On Saturday 3 March, 1962, Jim Furnell travelled to Fellows Park, Walsall. It was Jim Furnell’s first match for Liverpool Football Club. Jim Furnell conceded one goal on his debut. And Liverpool Football Club drew one-all with Walsall Football Club.â€

And that’s actually one of the more sparsely detailed accounts. There’s fifteen years’ worth of these match highlights (including the number of fans attending each game), peppered with locker room speeches, post-game conversations with opposing managers, and other behind the scenes anecdotes—not to mention a stirring invocation of the unofficial theme of Liverpool supporters, “You’ll Never Walk Alone.†Fifteen years following Bill Shankly and Liverpool Football Club “away from home, away from Anfield†and “at home, at Anfield,†match after match. I recognize that for some readers, that’s going to be a tough sell.

(more…)

19 June 2014 | read this |

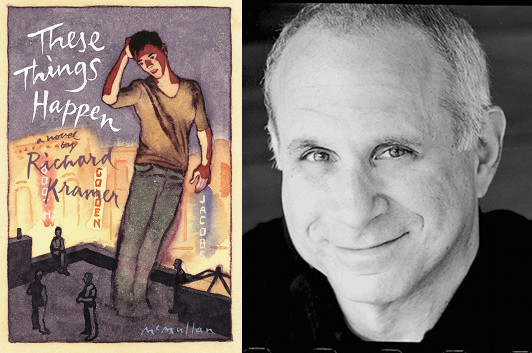

Richard Kramer & The Threads of These Things Happen

photo: Dick Avery

Richard Kramer, a writer/producer for television shows like thirtysomething and My So-Called Life, describes his debut novel, These Things Happen, as “a story about a modern family, set among Manhattan’s liberal elite.” It turns out, however, that some of its characters have deep roots in his experiences on the opposite end of the country, including the things he learned when he realized he’d been taking a key figure in his day-to-day life for granted and decided to do something about it…

The birth of the book goes back twenty-five years, maybe even more. When we were doing thirtysomething, it was so exhilarating and exhausting I wouldn’t drive home at the end of the day, but I’d go instead to an Italian restaurant a few blocks from my house. I did this four nights a week, often alone so I could work on scenes for the next day. The place became a habit, and I went there even after the show’s five years came to an end; they knew me.

The person who knew me best was the man who was combination captain/maitre d’/manager. He was around forty, dressed in a blazer and striped tie, always smiling and with some nice thing to say. I would call from the set and say I was coming in, and he’d say “Great, Richard. Do you want the patio tonight, or your usual table?” When I’d get there he’d show me to my seat and immediately send out some delicious plate with a few free somethings. Looking back, I calculate I had at least a thousand meals there, which is a lot of carbonara. And—here’s how These Things Happen comes in—I realized when the restaurant announced it was closing that I didn’t even know this man’s name. Maybe I knew it once, but what did it matter? He was there to be a prince of the pleasant, dedicated to making my life a little bit nicer. He didn’t need an identity beyond that.

Seeing this shocked me. Here I thought I was such a nice guy! But I wondered: How many other people do I render invisible because it’s too much trouble to endow them with a biography? And how many people do that to me? Why do we, unconsciously, but still with some selective design, limit our imaginations about those around us?

15 June 2014 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.