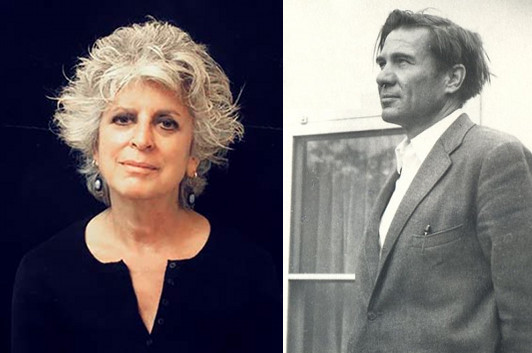

Michele Zackheim: The Sing-Song Passion of Galway Kinnell

photos: Charles Ramsburg (Zackheim); Nancy Carrick Holbert (Kinnell)

It’s National Poetry Month, and the novelist Michele Zackheim (most recently the author of Last Train to Paris examines her love of Galway Kinnell’s “Under the Maud Moon” (first published in 1971’s The Book of Nightmares, a few years after the photo above was taken). Anita Felicelli is also a fan, calling it “the last poem I loved.” As we’ll see, for Zackheim, it’s a personally significant poem on multiple levels…

In 2003, during one of the worst blizzards in New York City history, I met the poet Galway Kinnell at the stage door at Lincoln Center. It was my job to meet the poets invited to participate in “Poems Not Fit for the White House,” an evening of poetry organized by Not in Our Name, a movement against the war in Iraq. The event was created because Laura Bush had invited the poet Sam Hamill to attend a poetry symposium on Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, and Langston Hughes at the White House. Rather than enter enemy territory, he put out a call for antiwar poems to be sent to Laura Bush in his place. Thousands of poems arrived; the White House was furious and pointedly cancelled his invitation, although Hamill had already said no. Thus the poets’ movement against the war was created—and I met Galway Kinnell.

He was 76 at the time, three years older than I am now. I was so impressed that he had trekked into the city from the snowbound wilds of Vermont. (Now, of course, I would look upon it as a minor accomplishment, because I would do the same.)

After I had introduced myself and showed him to where he would be sitting, we talked. “What poem have you chosen to read?” I asked.

“The one about my son Fergus, my second child, and getting him milk in the middle of the night.”

I remember taking hold of his tweedy arm. “Oh, please change your mind and read ‘Under the Maud Moon’!”

“My dear,” he said. “If I had known, I would have brought it with me. So sorry. Why is it that poem that you like?”

And I froze, unable to articulate my feelings. I stumbled and faltered and was saved by the bell. It was Kinnell’s turn to read.

Every January, when I begin the poetry section of the year’s curriculum, I stand behind my desk and begin to read “Under the Maud Moon.”

On the path

by this wet site

of old fires—And my eyes tear up. But I never fumble, never stumble—and I read all six pages of this lovely poem. I’ve often asked myself, why this poem? Why not one of the hundreds of others that I love too?

It is the sing-song passion of a father who has understood the power of the birth of his daughter that sends me, along with Kinnell, toward both my dreams and my trepidations. It is this man who is not afraid to sound soft, and pliable, and fearful for his beloved daughter. It is this human being who is celebrating life with the power and glory of words.

And she who is born

. . .

the mist still clinging about

her face, puts

her hand into her father’s mouth, to take hold of

his song.It is a lesson for all us women who assume that most men don’t care—certainly not enough to write such a poem. But I think we are wrong. I hope so. Kinnell becomes a wandering singer of dreams, and of nightmares. He takes our imaginations and leads us to the end of the poem, with sodden wood in one hand and the “celestial cheesiness,” as he puts it, of the newborn Maud in the other.

6 April 2014 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.