Why Do We Even Do Criticism, Anyway?

In September of 2013, The New York Times Book Review launched a new column called Bookends. They’ve got a pool of eight columnists, and every week, they set up a different pair to answer “pressing and provocative questions about the world of books” like “Are We Too Concerned That Characters Be Likable?” or “What’s Behind the Notion that Nonfiction Is More ‘Relevant’ Than Fiction?” The answers in the first two months have struck me, with few exceptions, as fairly shallow—much like the questions themselves, concocted so as not to disrupt the digestion of the reader’s Sunday brunch.

The installment asking “How Do We Judge Books Written Under Pseudonyms?” particularly bugged me, in part because it’s a question with a fairly obvious answer: “The same way you judge any other book—on its merits.” Francine Prose basically ignores the question, offering a glib list of writers who published some work under pseudonyms, and some speculation as to why they might want to—eminently ignorable filler, from start to finish. It’s when Daniel Mendelsohn weighs in that things start to get a bit more interesting… but, I think, a lot more wrongheaded.

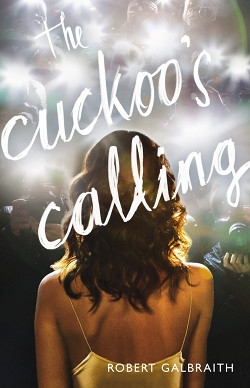

At first glance, Mendelsohn might seem to be tackling a more compelling variation of the question: “How ought we to consider novels written under pseudonyms?” Unfortunately, he also seems to regard the pseudonym—at least in the case of J.K. Rowling, who used the pen name “Robert Galbraith” to publish the novel The Cuckoo’s Calling—as a cheat. (He actually says “trick.”) Rowling took up the Galbraith name because she wanted the novel to be appraised without respect to her reputation; “but although the desire to be judged on one’s merits alone can strike us as noble,” Mendelsohn counters, he’s not sure “criticism untainted by knowledge of who the author is and what she has already done is desirable in the first place—or, indeed, valid.”

That’s right: Mendelsohn just raised the possibility that if you aren’t familiar with an author and her work, you won’t have anything valid to say about an individual book.

Of course, one might more usefully frame the issue by asking, “To whom should criticism be desirable and valid?” By talking abstractedly about the role of the critic, the essay doesn’t seem to waste much time escalating its response from “to Daniel Mendelsohn” to “to any right-thinking reader,” and that’s where I have to get off the bus. Now, I agree with Mendelsohn that connecting an individual work to the author’s oeuvre gives critics an opportunity to tell a very interesting story about that work—but that isn’t the only interesting story a critic can tell about the work, and to suggest, even in passing, that it’s the only valid way to tell a story about that work feels rather ridiculous. (In fairness, even Mendelsohn backpedaled from that implication when we had a polite exchange on Twitter the day after his essay ran.)

Specifically, I would consider the notion The Cuckoo’s Calling cannot be sufficiently appreciated without knowing about the role of J.K. Rowling as its true author, or that no criticism of The Cuckoo’s Calling that fails to reference Rowling’s authorship can be considered “desirable,” absurd.

14 November 2013 | uncategorized |

How Do We Judge Books Written Under Pseudonyms?

I have a confession to make: I had the opportunity to read an advance copy of The Cuckoo’s Calling, when it was still simply a debut novel by Robert Galbraith, and I chose not to.

I have a confession to make: I had the opportunity to read an advance copy of The Cuckoo’s Calling, when it was still simply a debut novel by Robert Galbraith, and I chose not to.

Although I have done some writing about mysteries and thrillers, they aren’t my primary area of focus, so I tend to be very selective about the ones I do read. And nothing about the catalog description of The Cuckoo’s Calling persuaded me this was a book I had to pick up. It sounded, by that account, rather generic: A down-on-his-luck private investigator lands a case that places him among the rich and powerful like a bull in a china shop and so forth. I read more books per year than the average person, and I still didn’t have time, or feel like making time, for one of those stories.

I had almost completely forgotten about the novel when news reports revealed that The Cuckoo’s Calling was, in fact, the work of J.K. Rowling, published under a pseudonym. I spend my days observing the publishing industry, so that gave me greater reason to find the book’s existence worth noticing.

The idea, as I understand it, was that Rowling had hoped to see how this novel might be viewed in and of itself, without reference to her previous literary output. Up until the moment of revelation, the answer appeared to be that the book was not viewed very much at all. It had gotten some notice in the advance trade publications, which aim at a degree of comprehensiveness in their attention to new releases, but the pockets of the mainstream media that address books hadn’t paid much, if any, attention to it, and comparatively few copies had sold. In and of itself, the market performance of The Cuckoo’s Calling did not herald great things for Robert Galbraith’s career.

After Rowling was forced into the spotlight, however, the novel’s sales skyrocketed. That raised several questions, one of them being: Had a good novel gotten lost in the shuffle because nobody recognized the name on the cover?

I feel confident in telling you: No, that’s not what happened.

13 November 2013 | better bookends |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.