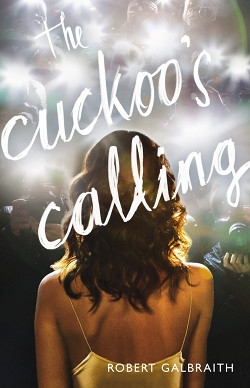

How Do We Judge Books Written Under Pseudonyms?

I have a confession to make: I had the opportunity to read an advance copy of The Cuckoo’s Calling, when it was still simply a debut novel by Robert Galbraith, and I chose not to.

I have a confession to make: I had the opportunity to read an advance copy of The Cuckoo’s Calling, when it was still simply a debut novel by Robert Galbraith, and I chose not to.

Although I have done some writing about mysteries and thrillers, they aren’t my primary area of focus, so I tend to be very selective about the ones I do read. And nothing about the catalog description of The Cuckoo’s Calling persuaded me this was a book I had to pick up. It sounded, by that account, rather generic: A down-on-his-luck private investigator lands a case that places him among the rich and powerful like a bull in a china shop and so forth. I read more books per year than the average person, and I still didn’t have time, or feel like making time, for one of those stories.

I had almost completely forgotten about the novel when news reports revealed that The Cuckoo’s Calling was, in fact, the work of J.K. Rowling, published under a pseudonym. I spend my days observing the publishing industry, so that gave me greater reason to find the book’s existence worth noticing.

The idea, as I understand it, was that Rowling had hoped to see how this novel might be viewed in and of itself, without reference to her previous literary output. Up until the moment of revelation, the answer appeared to be that the book was not viewed very much at all. It had gotten some notice in the advance trade publications, which aim at a degree of comprehensiveness in their attention to new releases, but the pockets of the mainstream media that address books hadn’t paid much, if any, attention to it, and comparatively few copies had sold. In and of itself, the market performance of The Cuckoo’s Calling did not herald great things for Robert Galbraith’s career.

After Rowling was forced into the spotlight, however, the novel’s sales skyrocketed. That raised several questions, one of them being: Had a good novel gotten lost in the shuffle because nobody recognized the name on the cover?

I feel confident in telling you: No, that’s not what happened.

I picked up the advance copy of The Cuckoo’s Calling and began to read without consideration to the author, focused solely on the story. (This was somewhat easier for me in that it had been years since Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, and I’d never read The Casual Vacancy, so I had no expectations for Rowling’s post-Potter prose.) And, with the caveat that I only made it about one-third of the way through, I would not by any means call it a well-written book.

As I said to someone at the time, it’s a good idea for a novel trapped in a bad novel. One might be able to discern the outlines of an intriguing story, but I found the prose stiff, the personalities unconvincing, and eventually I figured I had better things to do with my life than dig through Rowling’s prose to find some glimmer of entertainment.

I believe I would have reached exactly the same conclusion if, by some set of circumstances, I had been persuaded to read it strictly as a Robert Galbraith novel. I’d have given a debut writer a shot, found him lacking, and moved on.

You can tell a reasonably interesting story about The Cuckoo’s Calling as a pivotal moment in the J.K. Rowling oeuvre, of course. On one level, it’s the single most interesting aspect of the book’s existence. But, if we’d never found out about Rowling, you could have told an equally interesting story about Robert Galbraith’s work in relationship to the tradition of the private investigator in crime fiction–well, perhaps not equally interesting, because the book doesn’t seem strong enough to bear that weight, but a sufficiently interesting one, perhaps. (And it would appear that’s the story Rowling herself had some hope might have been told… if more people had noticed the book.)

“How do we judge books written under pseudonyms?” is, ultimately, a very easy question to answer. We judge them the same way we judge any other books, by the perceived quality of their prose — if we bother to read them in the first place.

in response to “How Do We Judge Books Written Under Pseudonyms?”

13 November 2013 | better bookends |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.