Read This: Full Fathom Five

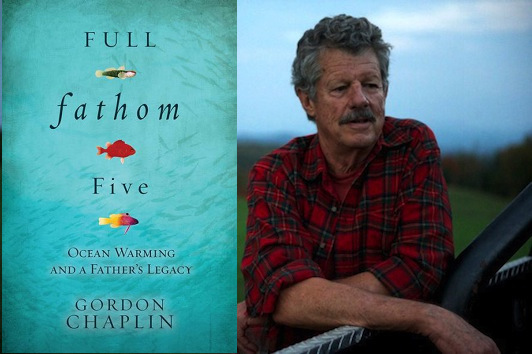

I recently met Gordon Chaplin to talk about his memoir Full Fathom Five, with an eye towards an episode of the Life Stories podcast. As sometimes (though fortunately not very often) happens, the sound on our recorded conversation wasn’t quite where I’d like it to be for public consumption, so that plan fell through—but I do hope that you’ll have a look at Chaplin’s story of picking up the legacy of his marine zoologist father, who co-authored the definitive Fishes of the Bahamas and Adjacent Tropical Waters. As a young boy, Chaplin actually helped his father with some of the research; fifty years later, he was invited to return to the Bahamas (although there was a period when, having been busted for possession, he was banned from the country) to see how aquatic life in the region had changed.

Full Fathom Five isn’t Chaplin’s first memoir; in Dark Wind (1999), he writes about attempting to sail across the Pacific with his first wife and losing her during a typhoon. They were holding on to each other through the storm, when she slipped out of his grasp and into the water; he’s still haunted by the choice not to keep plunging under the waves to try to find her, even though he knows rationally that he almost certainly would have died as well if he had. “Every time I go in the water, I feel close to Susan,” he told me, and that’s one of the reasons he took the title for this book from a passage in The Tempest that was recited at her funeral. That led us to a discussion of the allure of the dropoff, the point in the underwater topography at which the bottom suddenly plunges, like the face of a cliff. “I think that pull is stronger for me than it is for most divers, because I have these—I won’t call them ghosts,” he said, “but I do have a feeling that if I went down there, I might find the people I’ve lost.”

Chaplin also revealed how writing Full Fathom Five led to discoveries and realizations about his parents’ relationship that he probably wouldn’t have made otherwise. “I read all of my father’s diaries, I read his field notes, I read all of my mother’s diaries,” he recalled. “I read every single account I could find of my family, none of which I’d read before.” The biggest revelation may have been about his father’s transformation from a poor but adventurous young man who married into money and was recast as a rich woman’s consort. But he was sensitive to being branded as a gold digger, and refused to settle for that life. “Instead, he developed himself into a world-class scientist,” Chaplin explained, “and I hadn’t appreciated how that happened. I still don’t quite understand how it happened, but I can see now that it did. Before, I hadn’t respected that change [in his life] nearly as much as I do now.”

22 November 2013 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.