Author2Author: Michael Nava & Christopher Bram

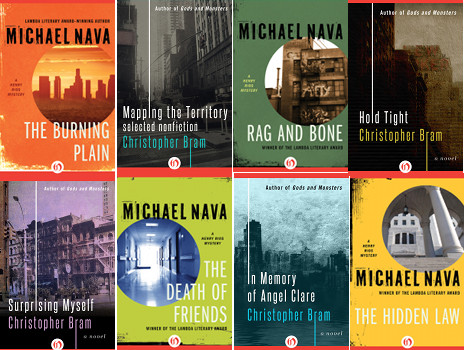

The folks at Open Road approached me recently and told me about how they were re-releasing the work of two great writers, Michael Nava and Christopher Bram, in ebook editions, and that the pair happened to be friends who might likely come up with an excellent exchange for an Author2Author feature. Well, I was familiar with some of Bram’s work as both a novelist and literary historian—in 2012, I reviewed Eminent Outlaws, his survey of 20th-century gay American literature—so while the two of them were formulating their questions and answers, I got hold of Nava’s first novel, The Little Death, and Bram’s debut, Surprising Myself, and started to bring myself up to speed. Of course, I couldn’t read everything that quickly… but I’m certainly looking forward to getting there over time.

Michael Nava: So, Chris, our first novels were both published in 1986 and here we are, like characters out of that Elton John song, “Talking Old Soldiers.” You know the one I mean? “I remember oh it’s years ago I’d say / I’d stand at that bar with my friends who’ve passed away / And drink three times the beer that I can drink today.” Or maybe like the movie queen in Sondheim’s Follies, belting out, “I’m still here!”

Christopher Bram: You’re right. It’s amazing we’re both still writing two and a half decades later. Maybe because we have so much to say? Neither of us has run out of things we need to talk about.

You write mysteries, but your Henry Rios novels are about so much more than solved crimes. Henry is a defense attorney and each novel he narrates functions as a mystery, with all the virtues of the genre. They are tightly constructed, cleanly written, full of smart details and expert dialogue. They are completely involving. But taken together, the seven novels form something much bigger, a large-scale moral portrait of one man’s life over fifteen years. We see Henry with his family, his boyfriends, his professional colleagues. We witness him dealing with AIDS, corrupt politicians, alcohol, and grief. He is that rarest of literary accomplishments: a plausible good man. I believe he is one of the great characters in recent American literature.

When you wrote your first Henry Rios novel, The Little Death, did you think it was only a one-shot work or were you already thinking of someone you’d live with for a long time? Did you plan Henry’s growth or just let it happen? Were you surprised at where he went?

Michael Nava: I didn’t set out to become a mystery writer or to write a series. I was just trying to teach myself how to write fiction. I started writing self-consciously when I was twelve, but until I was in my mid-twenties, I studied and wrote only poetry (I was going to be the W. H. Auden of our generation.) When I started law school, the poetry muse decamped but the obsession to write remained. I thought I’d try my hand at a novel, something easy to begin with, a mystery. I puttered at it, off and on, for several years while I was working as a prosecutor in Los Angeles. An older writer read it and told me it was publishable, so I sent it around, got reams of rejections before Sasha Alyson’s little gay publishing press picked it up. It was successful and Sasha asked me if I had another Rios story in me. It turned out I had six. I caught the wave of outsider mysteries going on in the 1980s and ’90s when writers like Sara Paretsky and Walter Mosley were redefining and invigorating the genre by casting as their protagonists characters who, in traditional noir, were victims or villains. Queer, Latino defense lawyer Rios was one of the new breed, like Paretsky’s feminist PI, V. I. Warshawski, and Mosley’s African-American PI, Easy Rawlins.

Michael Nava: I didn’t set out to become a mystery writer or to write a series. I was just trying to teach myself how to write fiction. I started writing self-consciously when I was twelve, but until I was in my mid-twenties, I studied and wrote only poetry (I was going to be the W. H. Auden of our generation.) When I started law school, the poetry muse decamped but the obsession to write remained. I thought I’d try my hand at a novel, something easy to begin with, a mystery. I puttered at it, off and on, for several years while I was working as a prosecutor in Los Angeles. An older writer read it and told me it was publishable, so I sent it around, got reams of rejections before Sasha Alyson’s little gay publishing press picked it up. It was successful and Sasha asked me if I had another Rios story in me. It turned out I had six. I caught the wave of outsider mysteries going on in the 1980s and ’90s when writers like Sara Paretsky and Walter Mosley were redefining and invigorating the genre by casting as their protagonists characters who, in traditional noir, were victims or villains. Queer, Latino defense lawyer Rios was one of the new breed, like Paretsky’s feminist PI, V. I. Warshawski, and Mosley’s African-American PI, Easy Rawlins.

Your nine novels have enormous range. You followed up the semi-autobiographical coming-of-age story in Surprising Myself with Hold Tight, which explores gay life in World War II–era New York, followed by novels about the impact of AIDS on a group of gay friends (In Memory of Angel Clare); a fascinating novel about a closeted American diplomat in the Philippines during the Vietnam War (Almost History); and your stunning book about the great movie director James Whale (Gods and Monsters), which was followed by novels set in Clintonian Washington, Victorian America, a bucolic Virginia college on the eve of the Iraqi war, and the contemporary New York theater world. Auden said of Yeats, “Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.” I wonder what are the through-lines that unite your seemingly disparate works, the themes and obsessions, the things that “hurt you” into your art?

Christopher Bram: I love the Auden line. Like you, I, too, read lots of poetry—although I never wanted to be a poet. But to tell the truth, I’ve had a relatively easy life and don’t think I’ve been “hurt” into poetry. Maybe I’ve been confused or irritated into it—trying to understand cruelty and stupidity. I’ve certainly been tickled into it—by love and happiness.

I often fear I suffer a storytelling equivalent of attention deficit disorder, always needing to try something new. I envy you finding a character who gave you a solid place to stand, a post from which you could explore a very wide world. But there are through-lines in my work. For one thing, all my books include gay characters. I include plenty of straight characters as well, as you do, too. But the gay presence stands out for us both, simply because we’re telling stories nobody else is telling.

But other themes keep reappearing in my books. One is work. Which might sound like a silly thing to mention, but I’m fascinated by the different jobs people have and how these jobs affect their lives. There’s a children’s book by the illustrator Richard Scarry, What Do People Do All Day? It’s a good question for adults, too. Freud said that the only realms where people can find happiness are love and work—he deliberately left out religion. Well, novelists are always writing about love, and I do, too, but I try to include as much work as I can. So there are military people in Surprising Myself and Hold Tight (I grew up in a navy town). There are government workers, journalists, and teachers in Almost History and Gossip. And there’s a movie director in Gods and Monsters. Everything but novelists. I have no desire to write a novel about a novelist.

You write about lawyering and you do it beautifully. For all our badmouthing of lawyers, it’s a very human, dramatic activity. You include good lawyers and assholes, smart judges and hack judges. It’s a rich world that you know firsthand and can make accessible to readers. And, in addition to the law, you write about two very different communities: the gay community and the Latino community. You are clearly loyal to both. How does that affect your writing? Are you afraid of hurting feelings or betraying principles? How much truth are you willing to tell your readers? Has it ever backfired on you?

Michael Nava: Yes, your novels are quite good on work, the nuts and bolts of it—I’m thinking of the theater world you so richly depict in Lives of the Circus Animals, which I just finished reading. I love that, because so much fiction assigns a character a job, but you never see him or her working, and work is one of the things that define us. Our work gives us a sensibility, a community. I tried very hard to convey that through Rios and his work in the criminal justice system. My upcoming novel, The City of Palaces, features a doctor in late-19th-century Mexico. I spent years researching medical education and practice because his work is central to his character.

As far as writing for my two communities, I think, like you, I feel my main obligation is to portray those communities in all their complexity, as opposed to as cardboard stereotypes, whether positive or negative. So the Latino detective in The Burning Plain is a corrupt asshole while the Latina politician who appears in a couple of the novels is smart, sharp tongued, ambitious but basically decent. Similarly, my gay characters range from good people to murderers. I’ve never heard anything negative from my readers, just the opposite—a number of my Latino friends loved the pompous, homophobic Chicano-studies academician in The Hidden Law and asked me who my model was. I demurred.

I just finished your two nonfiction works—your collection of essays, Mapping the Territory, which was delightful, and then I moved on to your last book, Eminent Outlaws, about some (cough) seminal gay American poets and novelists. What a pleasure! I say that gratefully. I believe strongly as a reader and a writer that entertaining the reader is a worthy objective of writing. What kind of obligation, if any, do you feel toward your readers?

Christopher Bram: I’m a huge reader myself and I love to be entertained. So yes, I, too, feel an obligation to entertain my readers. But entertainment can include many different things. Good pacing is important to me, as I know it is to you—there is no dead space in a Henry Rios book. And I like to surprise people. I think nothing can be more surprising than the truth. I love to present good people behaving badly, and bad people behaving well. I want to surprise the reader with the idea that this person could be you.

Okay, not all readers like to be surprised. I sometimes fear that the general gay reader just wants a story that’ll give him an erection and a good cry. What’s the T. S. Eliot line? “Humankind cannot bear very much reality.” But there are smart, demanding readers out there, people who want more, and I try to give it to them. I want to shake up preconceptions and stale beliefs. I want to change a few minds.

I wish I had more straight readers. Gay people regularly read straight writers, but straight people only rarely read gay writers. Okay, there are a few, but they’re exceptions. I don’t know why there aren’t more. We have terrific stories to tell—and they’re not only about sex. They’re about being different and trying to fit in and being misunderstood—stories that anyone can identify with.

Michael Nava: You make the point in a couple of your essays in Mapping the Territory that, in the conventional literary world, our experiences as gay men, and mine also as a Latino, are deemed special interest and parochial while the experiences of straight white guys are held up as universal. That’s not only demonstrably false, it doesn’t give readers enough credit for getting out of their comfort zones. Some of Rios’s most devoted readers are straight readers and I’m sure that’s true of your books, too. Now that we’re both digital, I hope more straight readers will find our work. There’s a lot in them that speaks to everyone’s experience of being human.

24 June 2013 | author2author |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.