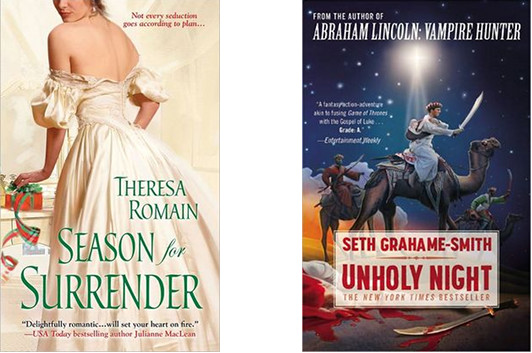

Read This: Unholy Night & Season for Surrender

As some longtime Beatrice readers may recall, once Thanksgiving’s over, I like to read Christmas stories. This year, after a recommendation by my friend Sarah, I decided I wanted to check out Theresa Romain’s Season for Surrender. I actually started with Romain’s first novel, Season for Temptation, which was put forward as a holiday-themed story—with the tag line “Mistletoe can lead to more than kissing…”—but it turns out that the Christmas element only takes up a few chapters in a story that spans months. That story, about a young aristocrat who arranges an engagement to a suitable lady only to realize that he’s attracted to her younger sister (and she to him, although of course he doesn’t know that for a good long while), has a lot to recommend it, although it’s a bit rough around the edges in a debut novel-ish sort of way. The second time around, Romain seems to feel a bit more confident, and it makes for a much more sustained pleasure.

Season for Surrender picks up just about where its predecessor left off: Louisa, the unsuccessful fiancée of the first novel, is looking for some excitement in her life and accepts an invitation to a ten-day holiday party at the estate of Alexander, Lord Xavier. She accidentally overhears a conversation between Xavier and her cousin and learns that she’s the subject of a wager between the two of them as to whether she can last ten days in the company of such a notorious rake. So she decides to turn the tables on them… Meanwhile, Xavier, who was portrayed as a bit of a dick in the first novel, is now shown to be a sensitive fellow, ill at ease with the role he has come to play in society, but unsure of how to reinvent himself—or whether anyone would take him seriously if he did.

The slow burn of Louisa and Alex’s relationship is handled quite well, and the firm boundaries of the holiday period and the country estate also work in the story’s favor. I liked that Romain didn’t lean as heavily on the “unconventional aunt” character as she did in Temptation; Lady Irving is a fun character, but a little of her can go a long way—and with two leads this strong, the supporting cast can be used less to supply “color” and more as interesting personalities in their own right (some, admittedly, more interesting than others). I would actually recommend starting with this novel, then circling back to its predecessor if you want to spend some more time in Romain’s world.

Unholy Night is a very different type of Christmas story, and one that I’ll admit didn’t fully hold my attention when it came out in hardcover a while back—mostly because I’d had little interest in Seth Grahame-Smith’s previous novel, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. When the trade paperback showed up in my mailbox in November, though, I decided to give it a whirl, and I’m glad I did.

The concept is straightforward: “the real story of the Three Wise Men.” It boils down even more simply to the story of Balthazar, a master thief known as “the Antioch Ghost.” He’s been captured by the Romans and delivered to King Herod, thrown into a cell with two other criminals, Gaspar and Melchior. After a daring escape, they ride out to Bethlehem, where they encounter a young couple and their newborn son who are also targets of Herod’s wrath…

This is the Nativity as action film, and there’s a few angles that come off as cartoonish; Herod’s decreptitude is like an ancient echo of Baron Harkonnen, for example, and I personally think Grahame-Smith relies a bit too much on ibises for POV narration in desert long shots. But I really loved how he gets across the terror when Balthazar witnesses the slaughter of the innocents. This isn’t just a blip in the story, a passing mention of something that happens between Jesus’s birth and the flight into Egypt—it’s a genuinely horrific act of tyranny, and the version laid out here makes the stakes powerfully real.

I also admire the ways Grahame-Smith grounds his characters. He takes Mary and Joseph’s religious faith seriously, and allows them to recognize and live with the burden of other people’s opinions about that faith. Balthazar in particular shows a contemptuous skepticism, but as he finds himself bound to the family for personal reasons, you’ll find his subtly changing outlook plausible. This turned out to be way more entertaining than I was prepared for it to be, going by the excerpt of AL: VH in the back of the book, it seems like Grahame-Smith has maybe made a major leap in his creative development? At any rate, I would commend Unholy Night to whoever is responsible for the next round of Hugo and Nebula nominations, as it’s one of the best fantasies I’ve read this year.

13 December 2012 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.