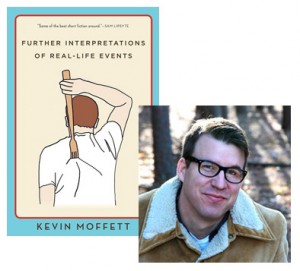

Kevin Moffett’s Hottest Short Stories

In the title story of Kevin Moffett‘s second short story collection, Further Interpretations of Real-Life Events, a struggling writer discovers that his father has also started writing short stories—and getting them published, which, since they share the same name, creates all sorts of awkwardness and anxiety for our narrator. It’s a rare but realistic enough dilemma, but through Moffett’s prose it comes across with an almost dreamlike quality. You’ll notice that same quality in “In the Pines,” in which a woman who’s recently gone into a retirement home is periodically visited by a Civil War soldier; it took most of the story, and a double-check of the book’s descriptive copy, before I was convinced he was a reenactor and not a ghost out of time (although the story would work equally well if he was). In this guest essay, Moffett doesn’t confine himself to a single short story that has inspired or influenced his writing, but the common thread through the ones he cites—”a long-earned strangeness, a much fuller, more interesting world than the I was inhabiting”—is something I think you might find in his own stories, once you give them a try.

The first short story I read was “To Build a Fire.” The first one I loved, that I read through and felt happily perplexed by and soon reread, was Barry Hannah’s “Return to Return.” At first, I liked the louder, voice-driven ones best, the seemingly formless howls: Grace Paley’s “The Long-Distance Runner,” Padgett Powell’s “Dump,” Leonard Michaels’s “In the Fifties,” Hannah’s “Ride, Fly, Penetrate, Loiter.”

I wanted to be grabbed by the arm and led places I’d never been and told startling things. (“I suck a dry dug daily. There’s grease from nothing, just torpor, in my fingernails.”) And if I was having a particularly delusional day, I might even be able to imagine my own stories in communication with, or riffing on, or subtly homagifying, the abovementioned ones, instead of baldly imitating them. (I was baldly imitating them.)

I also loved the ones whose circuitry was so buried, whose effects were so intuitive and hardwired to their form, the ones that rumbled with subterranean detonations whose ordnance I could only barely discern: William Trevor’s “The Day We Got Drunk on Cake,” Isak Dinesen’s “The Deluge at Norderney,” Chekhov’s “Gusev.”

I didn’t really categorize, not aloud anyway, but if I had it would’ve broken down along the lines of: these are hot and these are cold. Hot were the stories where I felt the bewildering intimacy of someone else’s mind, their perception and voice. The ones that gave access to a long-earned strangeness, a much fuller, more interesting world than the I was inhabiting: almost everything by Donald Barthelme and Isaac Babel, Susan Sontag’s “Unguided Tour,” Tomasso Landolfi’s “TK.”

Halfway through some of them, I knew I was going to have to find and read every word the writer wrote: Joy Williams’ “The Blue Men,” Denis Johnson’s “Work,” Flannery O’Connor’s “A Late Encounter With the Enemy,” Victor Pelevin’s “Sleep,” Jane Bowles’ “Two Serious Ladies,” and nearly all the writers mentioned above.

There was the one I read in Barry Hannah’s fiction workshop, which he quoted aloud from, shaking his head and saying, “I couldn’t make a sentence like that if you gave me a thousand years,” and what a surprise to see someone you’re in awe of in awe of someone else: Denis Johnson’s “Car Crash While Hitchhiking.”

And the ones I read the first time I visited San Francisco, buying the book in the morning and sitting in Golden Gate Park the entire day, neglecting all the other things I’d planned to do that day: David Foster Wallace’s Girl With Curious Hair.

And the one I read last night that reminded me of that day in San Francisco, over twelve years ago now, and made me go look to see if the book was still dog-eared on page 204 where I stopped reading that day—it was not: DFW’s “Good Old Neon.”

There was the one I read to my son and cried: Han’s Christian Andersen’s “The Fir Tree.”

And the one I read to a roomful of beginning creative writing students a few days later, because I was positive that I wouldn’t cry on the second reading of a story, especially to a roomful of beginning creative writing students—and cried: ibid.

I should also mention the ones that a friend had given me a copy of but I waited almost three years to read it because I was afraid the writer was mapping out the same territory I wanted to, but with surveyor’s rope and high-powered diagnostic equipment, instead of my knotted twine and junk-store binoculars: George Saunders’s Civilwarland in Bad Decline.

And the newer ones, which surprised and wrecked and thrilled me as much as any of the ones mentioned above, even though I’ve read probably sixty-eight thousand million published stories and student stories: Chris Adrian’s “The Changeling,” Lauren Groff’s “Delicate Edible Birds,” Chris Bachelder’s “Eighth Wonder.”

And the ones I pretended to read and never did. And the ones I resisted at first but gave in to. And the ones I loved but my students hated, and vice-versa. And the ones I forgot I’d read and then reread and remembered. And also Flannery O’Connor’s Collected.

26 March 2012 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.