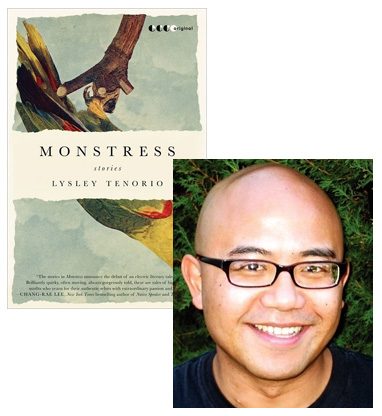

Lysley Tenorio On Dying & Character Development

The stories in Lysley Tenorio’s Monstress cover a wide range of Filipino and Filipino-American experiences, from a teen’s confused efforts to help his Imelda-fixated uncle exact revenge against the Beatles for a perceived offense during their 1960s visit to Manila to two elderly men who’ve spent their adult lives together in San Francisco’s International Hotel, from an actress in grade-Z monster movies who follows her husband on a desperate trip to Hollywood and discovers an unforeseen opportunity to a contemporary young man struggling to come to terms with the death of his transsexual younger sibling. There’s also a fantastic story, “Superassassin,” in which a teenage boy schemes to exact vicious revenge against his tormentors while caught up in his comic book-inspired fantasies. Tenorio comes by his portrayal of comics fandom honestly, as we’ll discover in this essay, and it’s also played an interesting role in shaping his literary vision.

I loved a girl once. For almost ten years. She was kind and selfless, a girl of unmatched courage, stronger than anyone I knew.

Then, when I was twelve years old, she died.

Her name was Kara. Kara Zor-el.

You might know her as Supergirl.

It was 1985. DC Comics had released Crisis On Infinite Earths, a 12-part series designed to streamline the overstuffed and overcomplicated DC Universe of multiple and parallel earths. In issue #7, Supergirl squares off against the Anti-Monitor, an all-powerful ruler of an Anti-Matter universe determined to destroy our own. It was a battle for the ages: just as the Anti-Monitor is about to kill her cousin, Superman, Supergirl swoops in, pummels the crap out of the Anti-Monitor, but on the verge of victory, she makes one fatal mistake: she looks away. With that, the Anti-Monitor unleashes his deadliest force-blast, killing her. But for the meantime, Supergirl has managed to disable his weapons, temporarily foiling his plans. “Thank heavens…” Supergirl says in her final breaths, “…the worlds have a chance to live…” Then, in Superman’s arms, she dies.

I finished reading it inside the comic book store, paid for it, then went with my sister to Pizza Hut. But I couldn’t eat. I felt numb. I felt dizzy. Across the table, my sister looked at me like I was an idiot, mourning a make-believe character, a girl of two dimensions. But I knew: This was grief. It had to be.

Lately, there has been a lot of dying in my classroom. In my freshmen fiction workshop, my students have been killing off their characters with cancer, brain tumors, car crashes, hit men, and comas from which they never awake. And they render these deaths with a gusto that’s admirable: they know the effect they want, and they go for broke, indulging every tear, breakdown, and bloodspurt. But for the most part, it doesn’t work. Reading these stories, we might find something recognizable or familiar (“Someone died at my high school too!”), but at most we understand these spectacular deaths, but we don’t feel them.

The problem isn’t necessarily the death itself; death is an intriguing and potent subject for fiction. The problem is the lack of life preceding it, the absence of that singular life force that every fictional character must possess in order to earn the right to die. We can only feel so much from the summarized life.

When I read these stories, I want to tell them about Supergirl. I was a living witness to the destruction of her home, Argo City (a sort of final city-remnant of Krypton, which exploded years before). I knew her as Linda Lee, the alias she assumed at the Midvale Orphanage, and that she had two pets: Comet the Superhorse and Streaky the Supercat. And when she wasn’t Supergirl, when she was simply Linda, she had the ambition and aimlessness of young adulthood—she was a high school counselor one day, an aspiring TV reporter the next, a soap opera actress soon after. I knew her powers and weaknesses, her losses and loves, her allies and nemeses, her victories and defeats. All that super-living, measured against a gloriously epic death scene. No wonder it worked. No wonder I mourned her.

6 February 2012 | selling shorts |

Life Stories #1: Heather Donahue

I mentioned, back in January, that I had big plans for 2012, and it’s time to unveil one of them: a new podcast series called Life Stories, in which I will be interviewing memoir writers about their lives and about the art of telling a story about those lives. The idea began with a chat on Twitter late in 2011, thanks to an invitation from Anna David, the author of Falling for Me, to moderate a conversation with about half a dozen different memoir writers. We all thought the Twitter chat went well, we hoped we could do it again, maybe make a regular thing of it… and, over December, I thought about some other things I would like to do with the concept, including an audio podcast. Anna was gracious enough to give her blessing, but I don’t think I would have recognized the opportunity it presents without her pointing me in this direction, and I’m truly grateful to her for that (and to all the authors who took part in that first chat, with whom I hope to talk again as part of this series eventually).

So: The first episode of Life Stories is a conversation between me and Heather Donahue about Growgirl: How My Life After the Blair Witch Project Went to Pot. In it, as the subtitle suggests, she writes about how, after deciding to recognize the end of her acting career, she moved to a small town in northern California and started growing medical marijuana. During the interview, I discovered not only that she’d been writing much of this story every day in her journal, long before she ever considered the possibility of Growgirl, but that writing was her first passion, even above acting:

“I came to acting from writing… I was reading and writing from the time I was really small. But I don’t really come from a family of readers, so acting sort of made more sense. It was a thing that my family could relate to more, so that’s what I got praised for more, and I think that’s why I ended up following that path. I think kids will generally go in the direction in which they’re praised, right? So for me Blair Witch was a blessing because it got me back to where I really wanted to be. This feels so much better to me. It feels great to have those long periods of solitude…”

(Donahue is currently teaching memoir writing at The Grotto; if you’re in the San Francisco area and serious about memoir writing, I’d suggest you look into her workshops.)

Listen to Life Stories #1: Heather Donahue (MP3 file); or download the file by right-clicking (Mac users, option-click).

PLUS: I mentioned up above that this podcast is one of the ways I wanted to work with the Life Stories concept. Here’s another: I’m aiming to record select episodes in front of a live studio audience. We’ll be recording a “pilot” of the live show in Manhattan on Wednesday, February 22, at Wix Lounge (10 W. 18th Street), a great writers’ space just a few blocks from Union Square, and in addition to recording audio from the show, we may even have some video highlights thanks to friends at the multimedia production company Arcade Sunshine Media.

The February 21 taping will have two guest stars: Rachel Shukert, the author of Everything Is Going to Be Great, and Reverend Jen, the author of Elf Girl. Join us at Wix Lounge at 7:00 p.m. that evening; RSVP on Facebook if you can, so we can estimate how many chairs we need to set out.

In the meantime, keep a look out for new Life Stories episodes here, and coming very soon to iTunes!

2 February 2012 | life stories |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.