Marian Schwartz on Getting the Voices Right

Andrei Gelasimov’s Thirst is a short but powerful novel about Kostya, a Russian soldier who, burned beyond recognition in Chechnya, now spends most of his days drinking alone in his apartment, sometimes venturing next door when his neighbor wants to scare her young son into doing what he’s told. Gelasimov’s narrative bounces around in time, from the present day to Kostya’s wartime experiences to his childhood memories, each juxtaposition bringing us closer to understanding him as a character. Marian Schwartz does an excellent job of easing English-language readers through the time shifts and, as she explains in this guest essay, a large part of that lies in giving her translation of Thirst an overall consistency while recognizing the specific demands of each scene.

Gelasimov makes it look so easy. One moment you’ve sat down to Thirst, and the next you look up and time has passed and apparently you’ve swallowed the book whole. Thoughts about what it means to be maimed and images of a refrigerator full of vodka, flashbacks to an exploding APC, and little Nikita’s Superman toy are swirling in your head—and you’re smiling.

That was my experience when I first read Thirst in Russian, and that is precisely the experience I endeavored to capture for my reader. Critical to this was accurately conveying Gelasimov’s subtle depiction of Kostya’s ongoing adaptation to life as a man with no face—a freak—while telling a classic army-buddies-take-a-road-trip story through telling use of the spoken word—the conversations—and the unspoken word—thoughts.

Gelasimov sequences through sections about Kostya’s present—his personal trials, his search with his friends for their missing buddy, his interactions with both his neighbor Olga and her son Nikita and with his estranged father and his new family—and his past, not just the immediate past of his injury in Chechnya but his childhood and the story of his parents’ estrangement and divorce. Space breaks signal each shift, but so do the changes in vocabulary and register. A conversation between Kostya and his friends sounds very different from his conversation with his father, as well it should.

Kostya’s memories of his youth and his mother and father quarreling become impressionistic, and so does the language. He recalls a day at the beach when his father’s wandering eye spurs his mother’s jealousy:

Because those young women were there. And my father was playing with them.

The ball sails over our heads. Smack! A ringing blow. My eyes follow its flight. I hear them laughing. Once more—smack! Again I look up. The ball is turning into the sun, and I have tears streaming from my eyes. I can’t see a thing. Smack! Next to me someone screams, ‘Get out of the water! Come here this instant! What is that you have?’ Smack! ‘Throw that filth out this minute! You’re going to get it!’ Smack! ‘Catch it, catch it!’ Smack! And then two times quickly—smack! smack! But the sound is a little different and very close. ‘Did you get that?’ And in reply a child’s cry. ‘Don’t cry or you’ll get it again.’ Smack! . . .

The paragraph continues with that dual use of “smack”—for the ball and for the child—as we picture the swirl of the beach crowd, to cinematographic effect.

19 December 2011 | in translation |

I’m Making Notes in My Ebooks. Come See!

I recently began consulting with the developers of Subtext, an iPad app that enables readers to annotate Google Books—or any other ebooks formatted with Adobe DRM, such as Kobo—and then share those annotations with their friends who also have the app, or with the entire network. When Subtext launched last month, they had several books pre-annotated by the authors themselves, including Lev Grossman’s The Magician King and Frances Mayes’ Under the Tuscan Sun. David Ulin shares his thoughts on Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, and while George R.R. Martin himself was unavailable, editors of some of the leading Song of Ice and Fire fan sites provide expert commentary on A Game of Thrones. My role is to focus on introducing even more authors and publishers to Subtext and encourage them to get involved, not just as a way to enhance their ebooks but to make real connections with readers through the dialogues that these marginal notes can spark. As the PaidContent article on the app’s launch suggested, “Here’s how social reading might actually work.”

I recently began consulting with the developers of Subtext, an iPad app that enables readers to annotate Google Books—or any other ebooks formatted with Adobe DRM, such as Kobo—and then share those annotations with their friends who also have the app, or with the entire network. When Subtext launched last month, they had several books pre-annotated by the authors themselves, including Lev Grossman’s The Magician King and Frances Mayes’ Under the Tuscan Sun. David Ulin shares his thoughts on Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, and while George R.R. Martin himself was unavailable, editors of some of the leading Song of Ice and Fire fan sites provide expert commentary on A Game of Thrones. My role is to focus on introducing even more authors and publishers to Subtext and encourage them to get involved, not just as a way to enhance their ebooks but to make real connections with readers through the dialogues that these marginal notes can spark. As the PaidContent article on the app’s launch suggested, “Here’s how social reading might actually work.”

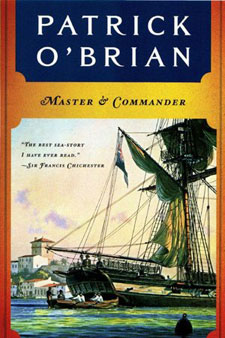

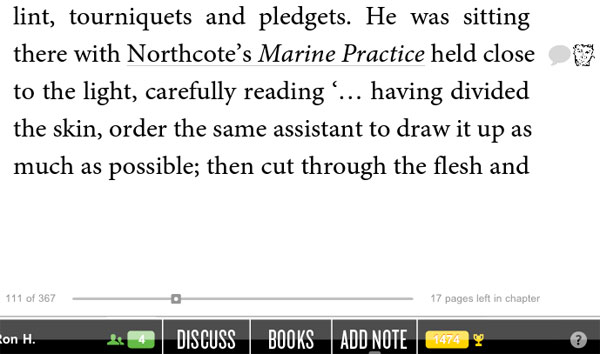

After taking the app out for a test spin with The Magician King—replying to some of Lev’s notes, and adding some of my own—I decided to take advantage of the recent release of Patrick O’Brian’s novels about Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin in their first electronic editions to embark on a huge annotating spree. So, starting with Master and Commander, I’m going to try to annotate one book a month until I’ve reread my way through the entire series. Here’s what it looks like in-device:

After taking the app out for a test spin with The Magician King—replying to some of Lev’s notes, and adding some of my own—I decided to take advantage of the recent release of Patrick O’Brian’s novels about Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin in their first electronic editions to embark on a huge annotating spree. So, starting with Master and Commander, I’m going to try to annotate one book a month until I’ve reread my way through the entire series. Here’s what it looks like in-device:

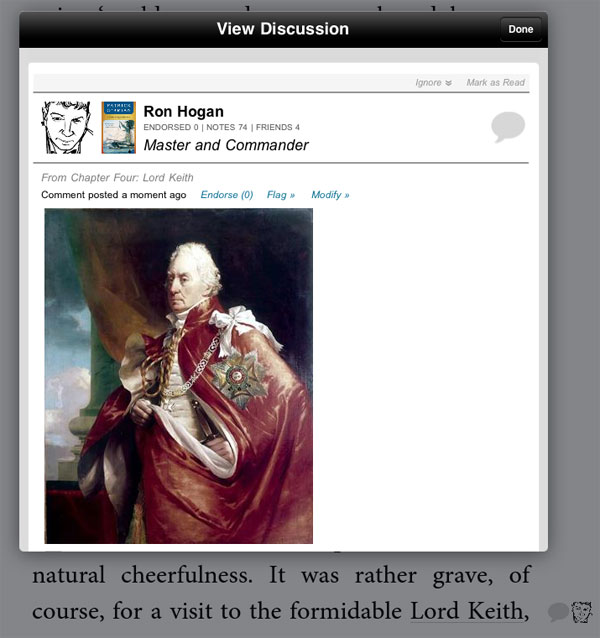

I’m not explaining every one of the sails on the great ships—there’s charts at the beginning of the book for that!—but every time I run across a historical reference I don’t quite get, I look it up, and I share what I find out. And when I come across a passage I particularly like, I talk a little bit about why. (And I do love O’Brian’s language so—an amazing blend of 19th-century voice with modernist innovations like stream of consciousness and cinematic jump cuts.) I’m also a big fan of the way that I can insert images or audio/video files into my annotations, so if an actual historical personage like Lord Keith makes an appearance, I can call up his Wikipedia portrait.

(W.W. Norton isn’t involved in this project in any way—it’s just something I’m doing because I love the books, and I want to show people Subtext’s fantastic potential.)

If you have an iPad, I encourage you to download the free Subtext app and start using it. Come hang out in the pages of Master and Commander; if you become my friend, you’ll find out whenever I start annotating another book. If you own that book, too, you can read my notes for free—and just as in most online bookstores, you get to read a sample before you commit to buying your own copy of the book. Oh, and if you’re an author or a publisher, and you think this is something you’d like to get involved with, get in touch with me, and I can put you in touch with the folks at Subtext to discuss ways to promote any books you begin annotating. And on that note, I’m hitting the books again…

16 December 2011 | uncategorized |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.