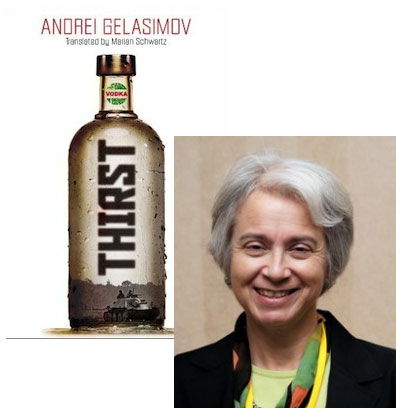

Marian Schwartz on Getting the Voices Right

Andrei Gelasimov’s Thirst is a short but powerful novel about Kostya, a Russian soldier who, burned beyond recognition in Chechnya, now spends most of his days drinking alone in his apartment, sometimes venturing next door when his neighbor wants to scare her young son into doing what he’s told. Gelasimov’s narrative bounces around in time, from the present day to Kostya’s wartime experiences to his childhood memories, each juxtaposition bringing us closer to understanding him as a character. Marian Schwartz does an excellent job of easing English-language readers through the time shifts and, as she explains in this guest essay, a large part of that lies in giving her translation of Thirst an overall consistency while recognizing the specific demands of each scene.

Gelasimov makes it look so easy. One moment you’ve sat down to Thirst, and the next you look up and time has passed and apparently you’ve swallowed the book whole. Thoughts about what it means to be maimed and images of a refrigerator full of vodka, flashbacks to an exploding APC, and little Nikita’s Superman toy are swirling in your head—and you’re smiling.

That was my experience when I first read Thirst in Russian, and that is precisely the experience I endeavored to capture for my reader. Critical to this was accurately conveying Gelasimov’s subtle depiction of Kostya’s ongoing adaptation to life as a man with no face—a freak—while telling a classic army-buddies-take-a-road-trip story through telling use of the spoken word—the conversations—and the unspoken word—thoughts.

Gelasimov sequences through sections about Kostya’s present—his personal trials, his search with his friends for their missing buddy, his interactions with both his neighbor Olga and her son Nikita and with his estranged father and his new family—and his past, not just the immediate past of his injury in Chechnya but his childhood and the story of his parents’ estrangement and divorce. Space breaks signal each shift, but so do the changes in vocabulary and register. A conversation between Kostya and his friends sounds very different from his conversation with his father, as well it should.

Kostya’s memories of his youth and his mother and father quarreling become impressionistic, and so does the language. He recalls a day at the beach when his father’s wandering eye spurs his mother’s jealousy:

Because those young women were there. And my father was playing with them.

The ball sails over our heads. Smack! A ringing blow. My eyes follow its flight. I hear them laughing. Once more—smack! Again I look up. The ball is turning into the sun, and I have tears streaming from my eyes. I can’t see a thing. Smack! Next to me someone screams, ‘Get out of the water! Come here this instant! What is that you have?’ Smack! ‘Throw that filth out this minute! You’re going to get it!’ Smack! ‘Catch it, catch it!’ Smack! And then two times quickly—smack! smack! But the sound is a little different and very close. ‘Did you get that?’ And in reply a child’s cry. ‘Don’t cry or you’ll get it again.’ Smack! . . .

The paragraph continues with that dual use of “smack”—for the ball and for the child—as we picture the swirl of the beach crowd, to cinematographic effect.

The register one least expects for the story of a traumatized vet is the child’s, but there are two separate lines with children, and one of them frames the entire story: Nikita, the little boy next door who won’t obey his mama and go to sleep so she asks Kostya essentially to frighten the boy into obeying her simply by showing up. When we first witness the scene, Kostya is firm with the little boy, if not stern, and the boy is terrified into going to bed. At the end, Kostya is still firm but not threatening, and Nikita obeys him willingly. They have a touching interchange after Nikita gets into bed:

One eye peeped out from under the blanket. Then the other. Dark as two plums.

‘I know.’

‘What do you know?’

‘I know I know.’

‘And what is it you know you know?’

‘That you’re not scary. You just have that face.’

‘Right, now off to sleep with you! Or else I’ll call . . . I’ll call your mama.’

He giggled again and hid under the blanket.

I love the adult-child banter, with its characteristic repetitions. I can just hear Nikita saying, “I know I know.”

Finally, a word on obscenities and expletives, which I always enjoy translating because to do it right, you have to know not the lexical meaning of the words used but who says them, when, and in what circumstances. Then, of course, you have to find the American obscenity or expletive that meets those same criteria. In Russian, blin means “pancake.” As I learned in translating this book, it is also a euphemism for bliad’—”whore,” or as some now say, “ho.” Being a euphemism, blin is relatively mild, used as an expletive when in English we might say “damn.” Blin appears often in the original text, and so does “damn” in the translation. So whenever you see “damn” in Thirst, you can think, Oh, pancake.

19 December 2011 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.