Should Indies Compete with Amazon on Pricing?

There’s been a lot of hype recently about the Indiebound reader app, which was developed by the American Booksellers Association’s Indiebound program to encourage consumers to buy Google eBooks from their local independent bookstores rather than buying Kindle-formatted ebooks from Amazon. (Yes, I spelled “ebooks” two different ways; in the case of Google, it’s trademarked with a capital B.) One of the chief selling points of this campaign is the assertion that you can buy ebooks from indies for the same price as Amazon. Unfortunately, while this is true in principle, it is not universally true in practice.

As many of you know, the “Big Six” publishers—the New York-based conglomerates generally, for better or for worse, acknowledged as the “core” of the book publishing industry—price their ebooks according to what’s known as the “agency model.” This means, that rather than charging booksellers a wholesale price, after which the bookseller can charge consumers a retail price of its own choosing, these publishers have chosen to set a fixed price for their ebooks, and then authorize individual retailers to sell those ebooks at that price. The only way the price changes is if the publisher decides to change it, and no retailer has a competitive price advantage.

Any ebooks from those publishers, then, do cost the same when purchased through an independent bookstore as they would at Amazon, or Barnes & Noble, or the Google eBookstore. So Robert K. Massie’s Catherine the Great, published by Random House, is $14.99 wherever you go, including Powells.com, the indie bookstore with whom I’ve had a commission-based relationship for several years. But what about ebooks from publishers who don’t use the agency model? Let’s look at Stephen Greenblatt’s National Book Award-winning The Swerve, published by W.W. Norton, as one example. On the day I’m writing this post, the Amazon Kindle edition is $9.43, a price that the Google eBookstore matches. If you want to read this book on a Barnes & Noble Nook, though, it’s $14.01—which is still a significant savings from the $23.92 you’d pay to buy the ebook from Powell’s. And at least one independent bookstore is charging the sticker price of $26.95.

It’s also worth considering that some independent publishers have Kindle-compliant digital editions for sale through Amazon with no counterpart editions available at the Google eBookstore… and thus not available through independent bookstores working with Google.

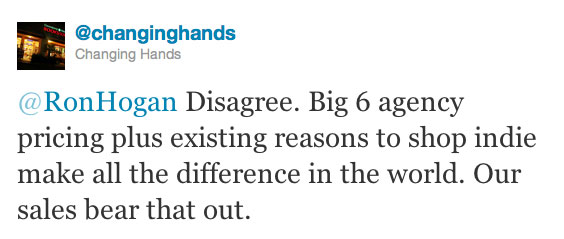

When I raised this issue on Twitter, I observed, “Announcing you charge the same price for an item as a national retailer isn’t impressive when said price is fixed by the manufacturer.” Other folks pointed out, and I recognize the truth in this, that it’s still worth mentioning when that national retailer has a prominent reputation for beating its competitors on price. Brandon Stout, who handles publicity and marketing for Changing Hands, an indie bookstore in Tempe, took further issue with my reasoning:

30 December 2011 | theory |

Read This: Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish

Longtime Beatrice readers might recall that I read a batch of Christmas-themed romances around this time last year; I meant to repeat the project this holiday season, but was only able to get to Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish by Grace Burrowes before the 25th.

Longtime Beatrice readers might recall that I read a batch of Christmas-themed romances around this time last year; I meant to repeat the project this holiday season, but was only able to get to Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish by Grace Burrowes before the 25th.

Although Lady Sophie’s Christmas Wish is the first in a sequence of novels spun off from Burrowes’ bestselling “Duke’s Obsession” trilogy (The Heir, The Soldier, and The Virtuoso), that doesn’t really come into play until you’re already well into the story. It begins at a London inn, where Vim (short for Wilhelm) Charpentier is trying to find a seat on a carriage to Kent in the middle of a snowstorm. He’s distracted by a squalling child, which is how he meets Sophie Windham, who was there to see the baby boy and his mother off on another carriage—except that the mother, a servant in Lady Sophie’s household, elects to pull a runner, leaving the child behind. Now it’s crucial here that Sophie doesn’t tell Vim that she’s a Lady, and the daughter of the Duke of Moreland, allowing him to think that she’s another servant in the mostly-empty household. (The Duke and Duchess have gone off to their country estate, where they are expecting Sophie, along with her brothers, who are the heroes of Burrowes’ previous romances.) This frees the couple up to spend several days (almost entirely) alone together with young Kit in a snowed-in house while Vim shows Sophie how to raise a baby—he’s had a lot of step-siblings—and they fall in love.

The story’s execution isn’t quite perfect: The scenes where Burrowes breaks away from Vim and Sophie to check in on the brothers who are on their way to collect her for the family reunion, or to note the anxiety of the Duke and Duchess and Vim’s aunt and uncle, are well-done, but they’re also distracting—though readers who are already Burrowes fans might welcome the opportunities to see how her heroes have been faring. On the other hand, you do need some sense of the brothers’ personalities for the back half of the book, as they react to discovering Vim and Sophie’s developing relationship, so it’s not as if you can cut those passages. The more significant problem, from my perspective, was that Vim’s backstory hinges on a slight suffered at the hands of Moreland so humiliating that it’s driven him to spend the last dozen years sailing the globe in order to be anywhere other than home—clearly a life-defining incident, and yet he fails to recognize that Windham is the Moreland family name. That part of the story just doesn’t seem plausible.

What does seem plausible, even under the contrived circumstances, is the slow burn of the attraction between Vim and Sophie. It gets a bit talky at times, in that “let’s lay the emotional subtext out on the table and dissect it” way, but there’s a core authenticity to the way the two interact, and then in the way that the hurt and confused Vim interacts with Sophie’s aggressive brothers. The dialogue swerves into anachronism occasionally (I’m pretty sure “shut up and listen” isn’t Regency-era speech), but no more so, at least to my ears, than is generally acceptable within the genre, and the motivations beneath the dialogue feel convincingly genuine. Vim in particular is a likeable hero, worldly but gentle if a bit pigheaded about clinging to the past, and his strengths as a character compensate for the weaknesses of Sophie as the sensible but lonely duke’s daughter who yearns to push the envelope of propriety to discover intimacy.

So, what about the Christmas aspect? In that regard, Lady Sophie fares slightly better than last year’s reading, in that the action is all confined to late December, and the immanence of Christmas is evident throughout. That said, it’s not so much a Christmas story that one wouldn’t be able to read it at any other time of the year, which is only proper considering that it fits into a larger sequence of Burrowes’ stories. And it definitely has me interested enough to pick up the copy of The Soldier that’s kicking around in my bookcase at some point…

28 December 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.