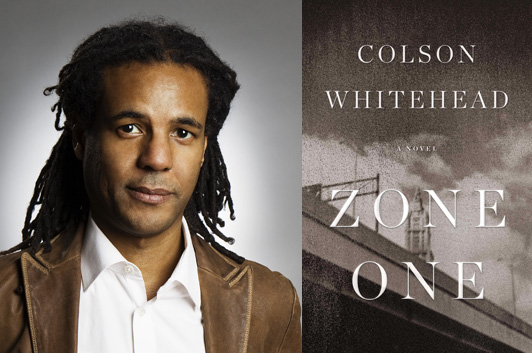

Read This: Zone One & the Literary/Genre Blur

Last month, one of my Character Approved book selections was Colson Whitehead’s Zone One, a novel about a foot soldier in the battle to reclaim lower Manhattan after the zombie apocalypse. It’s a great story, especially if you’re already a fan of Whitehead’s cool, detached voice, which fits this world—where everybody suffers from one form of “post apocalypse stress disorder” or another—perfectly. Like many classic zombie stories, Zone One has its share of satirical social commentary, including some unsettling echoes of Abu Ghraib, but at its core, this is a story of existential isolation… with some kick-ass action sequences.

Much of the critical reaction to Zone One centers around the “fact” that Whitehead is a “literary” author who’s decided to move into genre—which sort of ignores the weirdness of his first novel, The Intuitionist, but Whitehead himself doesn’t care about the distinctions between literary and genre fiction: “They don’t mean anything to me,” he says in an Atlantic interview. “They’re useful for bookstores, obviously. They’re useful for fans. You can figure out what’s coming out in the same style of other books you like. But as a writer they have no use for me in my day-to-day work experience.” Some critics, and critical institutions, care a lot, which is how you wind up with ridiculous, insipid statements like the lead sentence of Glen Duncan’s NYTBR review of Zone One: “A literary novelist writing a genre novel is like an intellectual dating a porn star.”

At first glance, one wonders why the New York Times would assign a “genre” novel to somebody who is so actively resentful of genre fiction and its fans—even as he makes big money from Knopf off werewolf stories—when they’ve already got a thoughtful critic of horror fiction in Terrence Rafferty. Maybe he just didn’t want to revisit zombies after surveying the topic back in August, or maybe the book review’s editors set out to deliberately provoke the sort of controversy that generates a lot of page views. Your guess is as good as mine. (Meanwhile, Charlie Jane Anders did a fine job of demolishing Duncan’s two-pronged cultural snobbery.)

Using Zone One as a prominent example, Joe Fassler wrote an article for The Atlantic about the increased presence of genre tropes in literary fiction, and I think that article gets at some salient points about how “today’s serious writers” are “yoking the fantasist scenarios and whiz-bang readability of popular novels with the stylistic and tonal complexity we expect to find in literature.” I’d suggest, though, that the “sea change,” to use Fassler’s description, isn’t in what “serious writers” are doing but in what “serious critics” are noticing and/or willing to discuss. We’ve always had writers who’ve combined “genre tropes” and “literary grace” in their fiction; some of them were published as science fiction or fantasy, some as mainstream literary fiction. (The principle holds true for other genres as well.) And this recent wave of high-profile novels with genre elements certainly hasn’t negated the persistence of realism as a literary device… More thoughts in this vein soon.

Leslie Brody & The Inspiration of Jessica Mitford

You know, we haven’t had a biographer drop by Beatrice in a while, so I’m delighted to share this essay from Leslie Brody about what led her to write Irrepressible: The Life and Times of Jessica Mitford and the inspiration she drew from her subject. I confess I haven’t had a chance to do more than glance at this title yet, for reasons that will become apparent over the next few days, but Mitford’s life sounds fascinating—I’m looking forward to eventually learning more.

I wanted to write a biography about someone who managed to hold on to the dreams of her youth. This elusive art was exactly what Jessica Mitford, as writer and provacateuse, triumphantly practiced all her long and adventurous life.

When I first read Mitford’s memoir Hons and Rebels, I was charmed by her rebellious and funny voice, and delighted to discover that she had left home at seventeen and set off to change the world on a utopian model. My escape at the same age was considerably less dramatic and I was fortunate to find a home in a counterculture that supported my initial wanderings and exercises in journalism.

In the early 1980s, I found work as a part-time librarian at the same San Francisco College of Mortuary Science that Mitford had eviscerated in The American Way of Death (grateful for a job that demanded no credentials). Four mornings a week, I would sit at a gigantic oak desk, inhaling formaldehyde and the must of unopened books, as I revised the plays I’d begun to write. I would filch announcements off the bulletin boards for weekend workshops in “head reconstruction,†and “grief counseling Bar-B-Ques,†and stash these away. Nobody would visit my library for weeks on end, except one young mortician-in-training who desultorily flipped through some books, then finally asked me out. He thought I might enjoy a tour of the building and I did. I saw the classrooms, laboratories, embalming rooms, and in the back yard what looked like twenty plastic gasoline cans full of blood. Once as I was snooping on my own, amid the back issues of “Mortuary Management†and “Casket and Sunnyside,†I found a file folder marked “Jessica Mitford.” I wish I could tell you there were explosive secret documents inside but it was empty. I always thought she’d get a kick out that, but I never met her—that is until I started to research this book.

8 November 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.