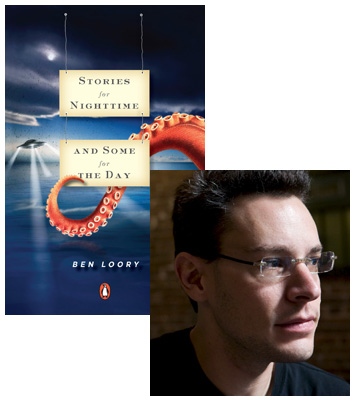

Ben Loory Keeps an “Appointment in Samarra”

I’ve been dipping into Stories for Nighttime and Some for the Day, the debut story collection from Ben Loory, whenever I get a chance these last few weeks. His short-short stories are the perfect length for reading on quick subway rides, and the dazzlingly weird details ensure that each one will stand out in your mind: The one where the duck falls in love with a rock, the one where a woman becomes infuriated by the popularity of a book filled with blank pages, the one about the man who self-published his poem, the one where the man refuses to move out of a graveyard even though the dead keep trying to drag him off to some unknown fate… and dozens more like them. For his guest essay, Loory’s chosen to write about a weird story that’s become even more well-known than the novel named after it—one that’s inspired him as a reader as much as it did as a writer.

I grew up in a house filled with books. My parents were both English teachers. They’d met in graduate school, in a seminar on Milton. We didn’t have a television. Over dinner, my dad would lecture us about Joyce; my mom would counter with Virginia Woolf. I remember learning all about T.S. Eliot and the objective correlative when I was seven years old.

Of course, I wasn’t interested in books like that. I was interested in books about space. Space, and ghosts, and monsters, unsolved mysteries… and then, when I was ten, I discovered Tolkien. From there it was off in fantasy for years; I went through everything I could get my hands on. And from there I verged on into horror, then into crime, and came out one day through detective fiction. At that point (this was when I was finished with college), I made the leap from Dashiell Hammett to Ernest Hemingway. I remember thinking it was an important moment. It felt like I was growing up.

I remember finding a list one day—it wasn’t too long after that. It was the Modern Library’s list of the 100 Best English-language Novels of the Twentieth Century.

I’m going to read all of these, I said.

And so that’s what I did. I read Faulkner, Conrad, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Nabokov, D.H. Lawrence. I read Jean Rhys, Henry James, Elizabeth Bowen; I read James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. Those books led to others that weren’t on the list; I read everything by every author I liked. After each book I’d call my parents and talk to them about it. Either one of them or the other; sometimes both.

This went on for a couple years. My parents and I talked a lot about style. And I found a lot of favorites as I went—I really liked Richard Hughes’ A High Wind in Jamaica. I really liked Tobacco Road and The Magnificent Ambersons. I really liked Catch-22. I really liked Ragtime and Under the Net. I really liked A Handful of Dust.

Then one day, something happened: I picked up John O’Hara’s novel Appointment in Samarra. It was one of the few books on the Modern Library list I still had never read. I remember opening it up, ready to start, and reading the opening epigraph. It’s a single paragraph—a retelling of an ancient tale, done by W. Somerset Maugham.

Here it is:

Appointment in Samarra

(Death Speaks:) There was a merchant in Baghdad who sent his servant to market to buy provisions and in a little while the servant came back, white and trembling, and said, Master, just now when I was in the marketplace I was jostled by a woman in the crowd and when I turned I saw it was Death that jostled me. She looked at me and made a threatening gesture, now, lend me your horse, and I will ride away from this city and avoid my fate. I will go to Samarra and there Death will not find me. The merchant lent him his horse, and the servant mounted it, and he dug his spurs in its flanks and as fast as the horse could gallop he went. Then the merchant went down to the marketplace and he saw me standing in the crowd and he came to me and said, Why did you make a threatening gesture to my servant when you saw him this morning? That was not a threatening gesture, I said, it was only a start of surprise. I was astonished to see him in Baghdad, for I had an appointment with him tonight in Samarra.

I remember finishing that paragraph and feeling like someone had punched me in the stomach. I read the story again and again, and sat there, marveling at it.

For weeks afterward I didn’t read anything else. I didn’t really see the point. I just kept thinking about that story. It was so clear, so simple, so incredibly intense. I couldn’t understand how someone had written it. It didn’t seem like anything else. It didn’t have the trappings of the novels I’d been reading. It just seemed like the pure and simple truth.

After that day, something changed. I stopped reading off other people’s lists. I started reading horror again, and science fiction, crime, unsolved mysteries. I started reading a lot of short stories—short stories of every stripe. For some reason I had never read many before. I thought they made a lot of sense.

It wasn’t too long after that, that stories started coming to me. They were very short, and very clear, and often they were fantastical. I never questioned why they came; I just wrote them down. I told them as simply as I could. And then one day my book came out.

31 August 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.