Read This: Rage & #YAsaves

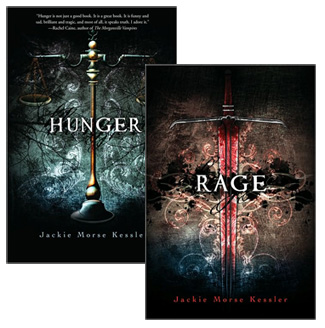

Under most circumstances, if a friend of mine had their novel as a featured book in an essay for a nationally prominent publication like the Wall Street Journal, I’d be ecstatic for them. Unfortunately, Meghan Cox Gurdon decided to use Jackie Morse Kessler’s Rage, about a 16-year-old girl who is recruited to become the personification of War, one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse, as an example of the “depravity” of contemporary YA fiction, suggesting that Jackie’s “gruesome but inventive take on a girl’s struggle with self-injury” is a type of novel that might actually do teenage girls who read it harm. “It is also possible—indeed, likely,” Gurdon claims, “that books focusing on pathologies help normalize them and, in the case of self-harm, may even spread their plausibility and likelihood to young people who might otherwise never have imagined such extreme measures.”

Under most circumstances, if a friend of mine had their novel as a featured book in an essay for a nationally prominent publication like the Wall Street Journal, I’d be ecstatic for them. Unfortunately, Meghan Cox Gurdon decided to use Jackie Morse Kessler’s Rage, about a 16-year-old girl who is recruited to become the personification of War, one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse, as an example of the “depravity” of contemporary YA fiction, suggesting that Jackie’s “gruesome but inventive take on a girl’s struggle with self-injury” is a type of novel that might actually do teenage girls who read it harm. “It is also possible—indeed, likely,” Gurdon claims, “that books focusing on pathologies help normalize them and, in the case of self-harm, may even spread their plausibility and likelihood to young people who might otherwise never have imagined such extreme measures.”

Plenty of people took on Gurdon’s larger argument—somebody should do something about all these wicked, wicked books, and if publishers won’t stop foisting them on us, parents should take steps to keep them out of teens’ hands—over the weekend. One point that was made over and over again on Twitter (under the #YAsaves hashtag) is that novels like Jackie’s, or Cheryl Rainfield’s Scars, or Lauren Myracle’s Shine—among others singled out by Gurdon—can let teens who are enduring horrific levels of adversity in their lives know that they are not alone, that hope is still an option. As Linda Holmes points out in her essay for NPR’s pop culture blog, “While the WSJ piece refers to the YA fiction view of the world as a funhouse mirror, I fear that what’s distorted is the vision of being a teenager that suggests kids don’t know pathologies like suicide or abuse unless they read about them in books… A lot of kids who don’t experience abusive dating relationships or self-harm or eating disorders? They already know somebody who does.”

I wonder what it means that Gurdon is horrified by the scenes that Jackie writes about a teenager who believes that cutting herself is the most effective way to retain control over her emotional life, but she doesn’t have anything to say about the scenes where that girl witnesses firsthand the effects of war on an unnamed desert nation. (Jackie also contrasts intimate and large-scale trauma in Hunger, the predecessor to Rage, in which an anorexic girl assumes the role of Famine.) Maybe it’s useful to think about how much suffering many of us are willing to shrug our shoulders at, whether in resigned acquiescence or apathy, as long as it’s not showing up on our own doorsteps. As long as we don’t have to see it too often on the TV, or read too much about it in the papers. But when we try to push those tragedies out of our line of sight, what other pain, closer to home, are we obscuring?

I couldn’t tell you for sure that’s what’s going on in this backlash against “dark” YA fiction; in all likelihood, there are lots of contributing factors, all tangled together in people’s minds. What I do know is that writers like Jackie are using fantasy to tell us about the pain and suffering they recognize in the world—and other authors, like Jay Asher (Thirteen Reasons Why) or Lizabeth Scott (Living Dead Girl) aren’t even couching it in fantasy. And while the fantasy sequences of Hunger and Rage are entertaining, when these novels focus directly on their protagonists’ traumas, they aren’t comfortable reading, not in the slightest. But what they describe is real, and even if it’s not something we are experiencing or witnessing in our own lives, we should be paying attention, and learning how to effectively support the people who are experiencing it when we do encounter them. Because, as Linda Holmes points out, it’s very likely that we will encounter them, and we may not always know exactly what to do, but we can try not to be completely ignorant. And for those readers who are in all too capable a position to judge these stories on their accuracy, they can (at their best) serve as a powerful lifeline.

7 June 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.