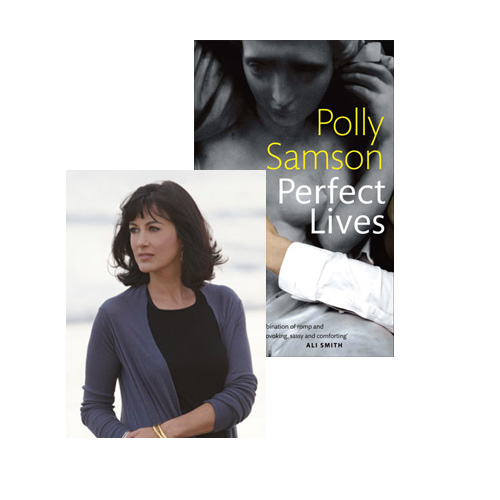

Polly Samson: Haunted by “The Apple Tree”

Polly Samson links the stories in Perfect Lives, her second collection, by overlapping characters in the same community—the family featured in one story will be the last clients of the piano tuner in the next story; his first client will be a friend to the unnamed woman whose first-person account of her marriage and family life is revisited several times. (This narrator also has an intense love of photography, drawing upon Samson’s personal passions). Some of her characters are just millimeters away from a breakdown, others are already behaving quite erratically, but a few have managed to carve out moments of comfort and passion; they all, however, tend to be at best tangentially aware of the dramas being played out around them. Samson has written the introduction to a collection of some of Daphne du Maurier’s earliest work, The Doll and Other Stories, so it makes sense that she would invoke du Maurier for this “Selling Shorts” essay—and the nervous energy in so many of her characters makes the choice even more apt.

As a child in London, I suffered so badly from nightmares that my mother took me to the doctor. I remember clearly the doctor in half moon glasses solemnly writing out a prescription for warm milk at bedtime, and yet I remember very little about the nightmares themselves: just a feeling of darkness, and trying to run, of gnarled roots and branches closing in around my head.

I stopped having bad dreams when we moved to Cornwall when I was eight. My suddenly peaceful sleep was odd, considering that we now lived in an old granite vicarage said to be haunted by a murderess and which was situated beside an ancient graveyard from which our terrier would bring the occasional femur. It wasn’t far from Fowey, where Corwall’s greatest novelist—Daphne du Maurier—lived and work, and this was real du Maurier country: open moors, windswept, sparsely populated… As I headed into my teens, I found I shared du Maurier’s passion for this wild landscape over which my own imagination had been freed to roam. I lost myself in her novels and slept peacefully at night.

I don’t know why I didn’t read her short stories until much later. I don’t think I ever came across them at the time; perhaps they weren’t even in print. I remember being surprised that two films that had truly terrified me—each causing a resurgence of nightmares—Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds and Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now were, in fact, based on du Maurier short stories.

As terrifying as I found the movies, I found that The Birds and Don’t Look Now wound the tension even tighter on the page than on the screen; du Maurier can do atmosphere and menace like no one else, and her short stories make my pulse race faster than her novels. In the smaller space, she hasn’t had to think too much about pace or form, so the stories seem more instinctive. In the more concentrated form, she is able to tap into fears that are so deeply subconscious you don’t even know that they are yours.

20 May 2011 | selling shorts |

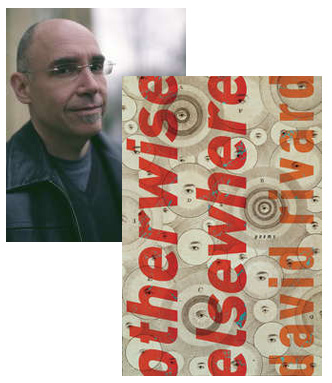

David Rivard, “How Else to Say It”

And the guilt that must be got rid of

all one’s life

how does my neighbor feel about that?

these appearing but feckless days

vain or proud

with riverine lavender & lupine in hand

a true lion of Judah is what

he is

while waiting for a light snow cover

and insulin

there’s slush on his G-Unit sneakers

muffin crumbs on his scarf

an aging incendiary

cosmopolitan but unfussy

back from an early morning Mass

and Holy Communion.How else to say it

except that it’s not such a bad way to make a living

bringing home

some sign as unshakeable as ashes

on this particular Ash Wednesday’s forehead

the quiet clear reminder of a smudged thumbprint

above his eyes

but in those eyes

a shine like the feeling inexplicable

to anyone lacking the sweet understanding

of a dog in boyhood

that to pee against the mossed bark of Juniper pine

is to be real in your soul.

Otherwise Elsewhere is the fifth collection of poems by David Rivard. You can read “Forehead” and “Lives” at Rivard’s website; the Academy of American Poets has “Plural Happiness.” The collection also includes “Townie Gossip (Since You Asked)” (AGNI Online)” and, of course, “Otherwise Elsewhere” (although the version published in American Poetry Review is markedly different than the one in the book). And the literary website Numéro Cinq posted four more poems.

“What I’ve always been interested in is moods—my own and the world’s,” Rivard said in a 2006 interview, “and, often, that is about as close to subject matter as I can get now. And anyway, our emotional lives are so complicated, rich, and full of illusions and blind spots. So the purpose of writing a poem in some ways is to be surprised by discovering this thing that you didn’t know about yourself or the world. In that case, the stories you tell yourself are the least interesting thing about you. And almost always untrue. Or not true enough.”

19 May 2011 | poetry |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.