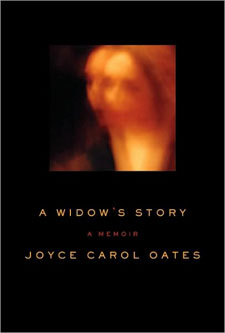

Read This: A Widow’s Story

Although I’m probably best known to Shelf Awareness readers for my science fiction and fantasy reviews, that’s not all I do. Yesterday, I reviewed A Widow’s Story, Joyce Carol Oates’ memoir about the despair and grief she went through during her husband’s fatal illness and the months immediately following his death. It’s a powerful and surprising read—for all the creative activity of her public life, Oates in private comes across as a very passive and fragile woman—and though I wouldn’t exactly call it inspirational, I do believe “we should appreciate not only how Oates has pulled herself back from the brink of despair but also how she has been able to articulate a despair that all of us are in time likely to feel, to reassure us that this raw pain is both normal and survivable.”

I also did a Q&A with Daniel Halpern, who edited A Widow’s Story for Ecco, and among other topics we discussed the experience of working with a writer of Oates’ caliber:

“She writes very carefully. People feel that because she writes so much, she doesn’t revise, that this all shoots out of her and she can write book after book, and that’s absolutely not true. Having worked on her books for a long time, I can tell you she doesn’t make very many mistakes… It’s a joy to edit somebody who writes a finished book, and the kind of work that I would do as an editor is pretty superficial.”

This book was more complicated because given the nature of the book, and because she had never written a book like this, she was nervous about it. She did something she had never done before, which was to show me parts of the book before it was finished, and she showed other people parts of the book. That’s very unlike her; usually, you get the book when it’s done, and mostly it is done. This was a whole different process for her. She was writing it as she was living it, and it was a very intense experience for her.

Some of the other coverage of A Widow’s Story I’ve seen in recent days has harped on the fact that Oates remarried roughly a year after the time she writes about in this memoir, which she doesn’t address at all, and whether or not the reviewer (or readers) ought to feel cheated by that omission. I don’t see it: That’s just not the story Oates wanted to tell. Memoir isn’t a promise to the reader, it’s a trick—an illusion of transparency, if you will. OK, maybe that’s not quite fair: The memoirist can be transparent, about the things she chooses to be transparent about. But that choice is always bounded by creative decisions, and even if we’re assuming a memoirist who is being fundamentally honest and not deliberately distorting, those creative decisions refine away the “raw data” that doesn’t fit the chosen narrative. And so it is here: Oates isn’t writing a story about “getting better,” she’s writing a story about the immediacy of struggling through the worst kind of emotional pain. Instead of griping about the memoir we didn’t get, let’s stick with the one we did.

16 February 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.