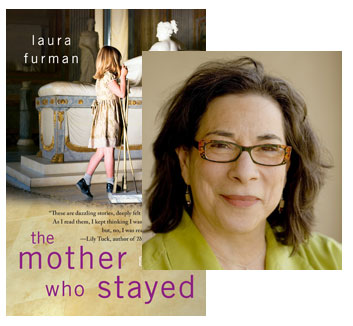

Laura Furman Savors “A Dill Pickle”

Laura Furman first came to my attention six years ago, some time after she’d become the series editor for the O. Henry Prize collections, and I asked her to discuss how she chose the short stories each year. Her eye for what makes a story work is refined by her own practice; in her latest collection, The Mother Who Stayed, Furman creates a “concerto” of nine stories, arranged in three sets of three—each trio has a single core, but they don’t form simple narratives. Events in one story become a distant history probed by a character in the following story, while the unexpected new revelations of that story color our understanding of the relationships depicted in the third. Furman presents these tales with no commentary beyond the simple fact of juxtaposition; it’s up to you, the reader, to make the connections… something to think about as you consider what Furman sees (and admires) in the work of Katherine Mansfield (1888-1923).

(P.S.: Furman’s book tour kicks off tomorrow in her home town of Austin; New Yorkers can meet her next Monday at the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble.)

AND then, after six years, she saw him again. He was seated at one of those little bamboo tables decorated with a Japanese vase of paper daffodils. There was a tall plate of fruit in front of him, and very carefully, in a way she recognized immediately as his “special” way, he was peeling an orange.

I flinch when a story opens with “And.” It seems an easy, even a lazy way to set the reader in the story; that little word implies that not only are we there in the present of the story but that we have been there all along. “And” is a continuation, not a beginning.

The use of the word startles me each time I re-read Katherine Mansfield’s “A Dill Pickle.” Mansfield’s opening is a little mannered, a little young but it works, and I go on reading the story as if it were new to me.

If Katherine Mansfield were alive today, she would probably be comfortable with a Facebook page, her own website and blog, and she might live in Brooklyn, alongside her contemporaries. She was a daring young woman, very pretty, thrilled to be gone from her native New Zealand, never very self-preserving or thoughtful. Her actions were dictated by her passions, and by her interest, almost a belief, in novelty and rebellion. Her experiences of abortion, gonorrhea, and tuberculosis make her seem contemporary also. In reading her biography—and there’s an excellent one, Claire Tomalin’s Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life—the sympathetic reader wishes that Mansfield had been born in the 1970s when so many of the circumstances that tripped her up and wasted her short life might not have been fatal, thanks to antibiotics and penicillin. Making poor choices in a husband and in lovers would still be an option.

“A Dill Pickle” takes place in a café and narrates the chance reunion of two lovers. She rejected him, he left and traveled to places she dreamed of. Meanwhile, she’s fallen on hard times, and as he tells of his adventures and of how she hurt him, she regrets losing him. Soon he demonstrates that he is the same selfish, mean, self-absorbed creature he used to be, and, without a word of farewell, she slips away from him and from the story.

The beauty of “A Dill Pickle” lies in the seamless turns of the heroine’s feelings and in the tennis game of their conversation and reflections.. The reader is expected to keep up. Perhaps that’s why Katherine Mansfield chose to begin her story with “And.” She is warning that you are to be included in the story and that, as in life, the action will not halt for explanations or excuses.

Mansfield was influenced by Chekhov’s short stories, which in her time were just being translated into English and published widely. I wonder if today’s writers know how much Katherine Mansfield has influenced them.

“A Dill Pickle” is a wonderful example of what the short story can do. It has the light and sketchy quality many of Mansfield’s short works do. This one also has all the weight of life, and gives its reader the characters’ past and present almost simultaneously. The story’s lightness and flow give it a permanent modernity. “A Dill Pickle” reminds me of how little needs to be said or explained for a story to be vivid. When I choose to explain or interject the authorial voice in my own fiction, I feel that I’m using a precious and rare resource—one that must be handled with caution.

Copyright © 2011 by Laura Furman

31 January 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.