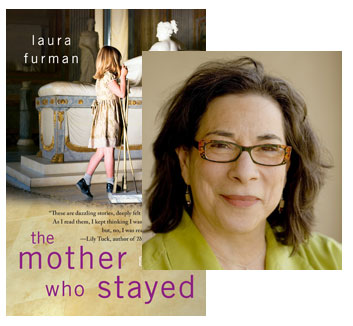

Laura Furman Savors “A Dill Pickle”

Laura Furman first came to my attention six years ago, some time after she’d become the series editor for the O. Henry Prize collections, and I asked her to discuss how she chose the short stories each year. Her eye for what makes a story work is refined by her own practice; in her latest collection, The Mother Who Stayed, Furman creates a “concerto” of nine stories, arranged in three sets of three—each trio has a single core, but they don’t form simple narratives. Events in one story become a distant history probed by a character in the following story, while the unexpected new revelations of that story color our understanding of the relationships depicted in the third. Furman presents these tales with no commentary beyond the simple fact of juxtaposition; it’s up to you, the reader, to make the connections… something to think about as you consider what Furman sees (and admires) in the work of Katherine Mansfield (1888-1923).

(P.S.: Furman’s book tour kicks off tomorrow in her home town of Austin; New Yorkers can meet her next Monday at the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble.)

AND then, after six years, she saw him again. He was seated at one of those little bamboo tables decorated with a Japanese vase of paper daffodils. There was a tall plate of fruit in front of him, and very carefully, in a way she recognized immediately as his “special” way, he was peeling an orange.

I flinch when a story opens with “And.” It seems an easy, even a lazy way to set the reader in the story; that little word implies that not only are we there in the present of the story but that we have been there all along. “And” is a continuation, not a beginning.

The use of the word startles me each time I re-read Katherine Mansfield’s “A Dill Pickle.” Mansfield’s opening is a little mannered, a little young but it works, and I go on reading the story as if it were new to me.

31 January 2011 | selling shorts |

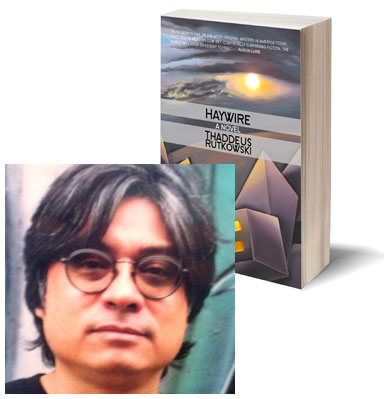

Thaddeus Rutkowski & Brautigan’s Planks of Sugar

Haywire is a series of vignettes narrated by an unnamed figure who, like Thaddeus Rutkowski, is the son of a Polish-American father and a Chinese mother—as you’ll see below, Rutkowski doesn’t hide the autobiographical elements; the protagonist’s first name, though not fully revealed, is even revealed to begin with “T.” But Haywire isn’t a straightforward account of a life, even in fictional form: It presents incidents without explanation or overt retrospective analysis; it skips over large swathes of time; almost nobody in the entire text has a name. And yet the story is still full of resonances and subtle through-lines; in this essay, Rutkowski tells us a bit about another author whose own “flash stories” influenced his style.

In high school, I really enjoyed reading Richard Brautigan’s books. It wasn’t just the content (the hippie lifestyle, the artist/fisherman’s vision) that drew me in, but the way that the author created “novels” out of brief, seemingly unrelated chapters. Some of these chapters contained fewer than 100 words, yet they were complete in themselves. What held them together was a sensibility, an outlook that stayed the same throughout the books.

Re-reading a couple of Brautigan’s books recently, I found the same sense of newness and whimsicality I’d encountered as a teenager. Reading from one “chapter” to the next, I didn’t know what to expect, yet each new passage added to what came before. In the prose book In Watermelon Sugar, for example, the buildings are made of planks of sugar. These planks are pressed at a sort of sawmill, and they come in different colors and varieties (e.g., “soundless sugar”). The planks serve their purpose: They bring a sweetness to the main community, iDeath, and, of course, they hold the buildings up. By repeating the metaphor, Brautigan links disparate scenes in the book.

When I began to write creative pieces myself, I didn’t know how to categorize them. Should I call them fiction or poetry? Those were the two main choices, though my pieces also had a strong autobiographical side. I didn’t consider labels like flash fiction, prose poetry, or mixed genre. (Those headings hadn’t been promoted yet.)

So I saw my pieces as short stories. They contained sentences and paragraphs, as well as characters and dialogue. But I kept everything brief. Much of my work concerns my childhood family, so instead of naming people, I used the words “mother,” “father,” “brother” and “sister.” My narrator was always the first person “I.”

30 January 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.