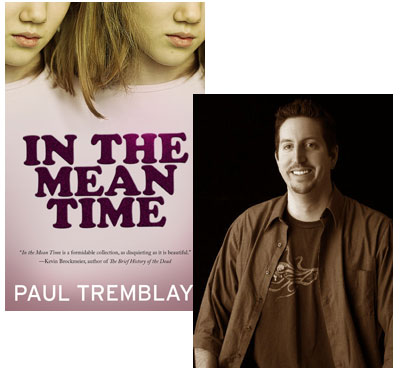

Paul Tremblay: “Man The Flying Saucers”

You’re going to want to read every short story in Paul Tremblay‘s collection, In the Mean Time, but here’s the thing: You can’t read them all at once. Heck, you can’t read more than one or two stories like “The Teacher,” or the really unsettling ones like “The Blog at the End of the World” and “It’s Against the Law to Feed the Ducks,” without your subconscious kicking back at you later that evening while you sleep. (Try “The Two-Headed Girl” on for size; it’s disturbing, but not quite as disturbing as some of the others—it even has its darkly funny bits.) I first met Paul when he read at the Center for Fiction in 2009, and I knew he had some awesomely weird stories in him, but I didn’t know then that they were anything like these. And it seems like we readers might not be able to appreciate his voice were it not for one story in one college class, as he explains here…

I hope this doesn’t sound trite, or like some sort of put on, but I’m not overstating when I say that Joyce Carol Oates’s “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?†changed my life.

I was 21 years old, a second semester senior, and taking my first college lit class. My excuse is that I was a mathematics major. Well, a double major: math and humanities (long and mostly boring story as to how that happened), but yeah, my humanities consisted of a hodge-podge of philosophy, history, and music courses, plus the one lit class. Of course, some of my best friends were English majors (including my future wife, Lisa), but the proud math undergrad that I was obnoxiously proclaimed that English majors/professors/hangers on just made it all up. The truth was I wasn’t confident in my own critical reading ability and I certainly wasn’t a reader of my own free will.

Oddly enough, math guy was totally mesmerized by Professor McLaughlin. It didn’t hurt that he was cool enough to be a fan of the Dead Boys, Mission of Burma, and Husker Du. He knew how to help connect me to the text through music. And, of course, he had us read “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?†It’s the story that made me fall in love with reading, and shortly thereafter, writing.

I’ll never forget my first, simple, visceral reaction to the story: I didn’t know there were stories/books out there like this.

I was initially struck by how the story’s structure was deceptively simple. The characters and plot were all built off of dichotomies.

Connie is fifteen years old and is as thin and pretty as her older sister isn’t. She goes out with her sister’s friends ostensibly to see movies and hang out at a mall plaza, only that’s not what they’re doing, what they’re up to. Connie spends her time talking to and hanging out with boys. Connie is a kid. But she’s not a kid. Connie is described as pale and smirking at home, but bright and pink on these nights out.

“She wore a pull-over jersey blouse that looked one way when she was at home and another way when she was away from home.â€

On one of these evenings, a black-haired boy stares her down, points at her and says, “Gonna get you, baby.â€

One Sunday morning, her family (big sis; her shrewish, overbearing mother; her balding, aloof, and harmless daddy) offers her a choice: go to a dumb old family barbeque, or stay home alone, dry her hair in the sun, and daydream. Connie chooses to stay home.

The boy from the parking lot, the one who pointed at her, shows up in her driveway in his gold-painted convertible and with an odd friend in tow. The boy’s name—along with a groovy numerical code (well, groovy to this math geek, anyway)—is painted on the car too. ARNOLD FRIEND. Arnold tells Connie that she’s cute, that he wants her to come for a ride with him. Connie is intrigued, but also doesn’t trust him. Arnold becomes increasingly threatening with his persistent request to come for a ride.

So, there I was, the second semester senior math major, and the story ran me over, and more magically, it cracked the critical code for me. Here was a story full of A or B choices. Or, to get all mathematical, let’s call it a story in binary code. In binary simple Os and 1s are used to encode practically infinite collections of data and any manner of complex symbols, letters, and instructions.

All those Os and 1s in Oates’s story represent, possibilities, choices made and not made, and their string of consequences; intended and unintended, or unforeseen.

I was sitting there, 8 A.M. in McLaughlin’s class full of mostly freshman, thinking: This guy Arnold Friend, is he an old friend or is he an old fiend? At first glance he’s her age, but no, maybe he’s older, much older. There are lines about his mouth and eyes. He’s taller than Connie, which she likes, but maybe he’s shorter. He walks and stumbles onto the porch as if his boots are stuffed. His friend in the car, maybe he’s older too. A “forty year old baby.†Connie is protected only by the thin screen door she stands behind. She’s not protected. She doesn’t lock the door. She resists Arnold’s ominous requests and threatens to call the police, but for most of the story, it’s an empty threat. Arnold talks of love and gentleness, and of his own threats. He promises he won’t go in her house as long as she doesn’t call the police. He promises he won’t hurt her family if she comes with him willingly. There’s choice and there’s not choice. There’s no violence on the page, but it’s there. It’s there.

This seemingly simple story expanded rapidly, exponentially before my eyes. All those Os and 1s. All those possibilities.

Rereading this story now

eighteencough cough years later, I’m a much more accomplished reader and, hopefully, a somewhat accomplished writer, and I appreciate the beauty and nuance of her prose, the expert pacing and characterization, the biblical and classical references, the symbols, the clever revealing of details and the hiding of others. But the story, that story man, it still crackles with a raw sense of true menace.“Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?†is alive with the menace of possibility, which is the power behind all the very best works of short fiction.

Gonna get you, baby…

30 December 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.