Stephen Dunn, “In the Open Field”

That man in the field staring at the sky

without the excuse of a dog

or rifle—there must be a reason

why I’ve put him there.

Only moments ago, he didn’t exist.

He might be claiming this field

as his own, centering himself in it

until confident he belongs. Or

he could be dangerous, one of those

men who doesn’t know

why he talks to God.

I thought of making him a flamingo

standing alone on one pink leg,

a symbol of discordancy

between object and environment.

But I’ve grown so weary of inventions

that startle but don’t satisfy.

I think he must have come to grieve

a good friend’s death, and just wants

to stand there, numbly, quite sure

the sky he’s looking at is vacant.

But I see that he may be smiling—

his friend’s death was years ago—

and he might be out there to savor

the solitary elation of having discovered

what had eluded him until now.

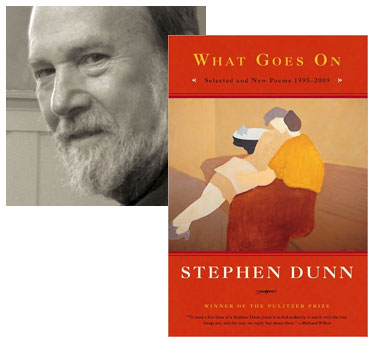

Two years ago, I featured “Madrugada” from Stephen Dunn‘s Everything Else in the World and mentioned that The New Yorker had published a new poem, “History,” that was not in that collection. You’ll find it in What Goes On: Selected and New Poems 1995-2009, along with “Talk to God” (the Poets Out Loud website), “And So” (How a Poem Happens, with commentary from Dunn on the creative process!), and “Zero Hour” (from the collection Different Hours, republished on Beliefnet).

It does not include “If a Clown” (also published in The New Yorker), which is a shame, because that’s a great poem. And maybe it’s a great illustration of a point Dunn made in an interview with Guernica back in 2004: “It seems to me that no matter how perverse or private you might think your attitudes are about anything, if you speak them well there’ll always be a few others nodding,” he said. “My best experiences with literature as a reader have been when something that I thought was freaky about myself, or something odd or private that I hadn’t told anybody, got articulated or enacted in a poem or story or a novel. It simply brings us into the human fold. Literature at its best is communal in that way.”

30 June 2010 | poetry |

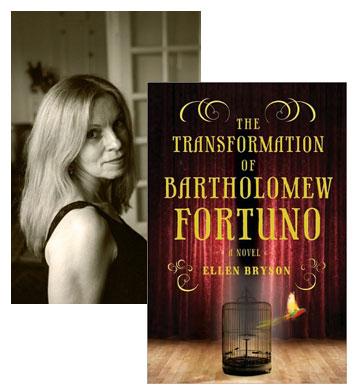

Ellen Bryson’s Dream of Bearded Ladies

The Transformation of Bartholomew Fortunato is narrated by “the World’s Thinnest Man,” one of many “Curiosities” living and working in P.T. Barnum’s downtown Manhattan museum in the spring of 1865. Bartholomew has a very elevated sense of his calling, but his self-image has quite a few blind spots, which come into play when his own curiosity is aroused by the arrival of a bearded lady to the museum; his fascination with her coincides with Barnum’s own desire to keep tabs on his latest star attraction. Ellen Bryson says the idea for her debut novel came to her in a dream—followed by a bout of research that led her to photos of Barnum’s cast. But, she explains, the character that spoke to her in a dream was not the one whose voice would give the novel its shape…

The Transformation of Bartholomew Fortuno started with an image of six bearded sisters in a circus tent. I’d just finished Angela Carter’s amazing novel Nights at the Circus—there’s nothing better than a book about bawdy burlesque women—and drifted off to sleep. I woke up at 3:00 that morning to a vision of six fabulous sisters lined up in the shape of a half moon, their bearded faces lifted to the tent’s canvas ceiling. One after the other, they shouted out their names, a spotlight glimmering off their cheekbones and their luscious beards.

Today, I remember only two names: the first, Esmeralda, a spry young thing who still whispers to me for space on the page. The second was Iell. I can still see her calling out “Iell,” her beard a stunning, burnished red, her face the face of an angel. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. How could a woman with a beard be so beautiful? And so feminine? As the rest of the sisters dissolved into a sepia background, I couldn’t help but wonder if others would see her beauty or only see the beard? What would it have been like to be her? What was her story?

Iell will tell me, I thought. But, for the life of me, no matter how clearly I could see her, Iell would not speak.

28 June 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.