W.D. Wetherell’s Most Vital Critique

There’s some good news on the SMU Press front—as you might recall, one of the reasons I featured four authors who had published short story collections at SMU last week was that the university was threatening to close down its publishing program, and I wanted to show you what a tremendous resource we’d be losing if that came to pass. Well, it’s still being shuttered, but according to the Chronicle of Higher Education, the university has decided to create a task force to decide whether it ought to resume publishing books and, if so, how to go about doing that. It’s not a happy ending—not by a long shot—but it leaves the door open a little longer.

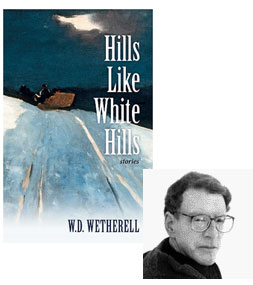

In the meantime, I have a few more SMU authors I wanted to share with you, starting with W.D. Wetherell and Hills Like White Hills. These aren’t always easy stories to read; in “The Master’s Hand,” for example, a recent widow finally lashes back at the years of emotional and physical abuse she suffered at her husband’s hands by taking it out on his dog. They are, however, powerful stories—and, in this essay, Wetherell reveals a youthful encounter with Daphne Du Maurier that set him on a long (and not always clear) path to a certain type of heightened literary realism.

Fate, the future, is fully capable of tapping a thirteen-year old’s shoulder, poking him or her in the ribs, pointing where to look, but somehow you wouldn’t expect this to happen in an eighth-grade English class in the last boring period of the day.

Mr. Goodwin, to his credit, tried hard to make our forty minutes with him bearable. He was an unconventional teacher—tweedy looking, reed thin, not afraid to voice his left-leaning opinions. Artsy, too. He took literature seriously, made sure we knew the names of contemporary writers like J. D. Salinger and Shirley Jackson, not just Washington Irving. His classroom was the hardest to find in the entire school, a real garret tucked away under the eaves; hidden there, he could teach his class any way he wanted.

Which involved, on the day fate struck, reading out loud to us Daphne du Maurier’s story “The Birds.” A few years later it would become famous via Hitchcock’s film, and du Maurier already had a big reputation as a best-selling Gothic novelist, especially for “Rebecca.”

24 May 2010 | selling shorts |

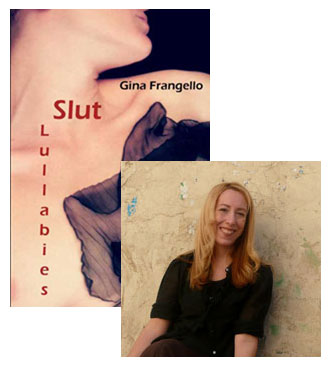

Gina Frangello Gives “The Hitchhiking Game” Thumbs Up

The characters in Gina Frangello‘s Slut Lullabies are living in extreme desperation: A woman watches her husband deteriorate from mental illness and wonders when their money will run out; a teenage girl comes up with a desperate plan to save her stepmother from her father’s abuse; a grad student already addicted to painkillers is on the verge of making a big mistake with one of her classmates. Gina’s in New York this weekend—appearing at ZieherSmith Gallery Saturday night and Word Brooklyn late Sunday afternoon—and to celebrate, I invited her to zero in a source of inspiration—which sounds very much like her own stories: painful to read at times but difficult to look away from once you’ve started.

Nobody writes sex like Milan Kundera. If he has a counterpart in American literature, it is probably Mary Gaitskill, though of course Gaitskill is of a different generation; by the time her debut collection Bad Behavior came out, Kundera had written some half-dozen books, some of which were first published in Czechoslovakia when she was a small child (and before I was even born). If one investigates Kundera’s American contemporaries, including those “pioneers” of erotic literary fiction such as Philip Roth and John Updike, the Americans can come across almost as adolescent boys titillated by their own naughtiness. It would take decades for American writers to truly explore eroticism, the power dynamics of gender/sexuality, and writing sex as a window to characterization with the nuance, complexity and sophistication Kundera had mastered before the American sexual revolution even began.

And since it is hard to toss a… well, in honor of Kundera, let’s say a bowler hat… without it landing on sex in one of his stories, to pick one that most exemplifies his prowess in this arena could seem difficult. However, the one story that knocked me on my ass when I first read it at the age of 20, and that I find myself teaching in Creative Writing classes again and again over the years is “The Hitchhiking Game” from Laughable Loves.

I love it for its purity, in a way. Most of Kundera’s work, while always carrying a powerful undercurrent of eroticism, concerns other matters on a “plot” level: heavy-hitting topics from the Prague Spring or the Communist repression of humor to riffs on classical music or Goethe. In “The Hitchhiking Game,” by contrast, the story is deceptively simple. A man in his late 20s and his girlfriend (referred to only as “the young man” and “the girl,” à la Hemingway) have a scant two-week holiday from their dreary Czech jobs and, on their first day of a trip, fall almost accidentally into a role-playing game where the girl pretends to be a seductive hitchhiker the young man has picked up. Jealousy—first hers that her slightly-older lover has in fact been in this sort of casual pick-up situation with many women before her; then his at seeing his shy and innocent girlfriend, whom he has on a pedestal, shedding her inhibitions and revealing a primal, anonymous sexuality—begins to flare as the game escalates in intensity.

21 May 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.