W.D. Wetherell’s Most Vital Critique

There’s some good news on the SMU Press front—as you might recall, one of the reasons I featured four authors who had published short story collections at SMU last week was that the university was threatening to close down its publishing program, and I wanted to show you what a tremendous resource we’d be losing if that came to pass. Well, it’s still being shuttered, but according to the Chronicle of Higher Education, the university has decided to create a task force to decide whether it ought to resume publishing books and, if so, how to go about doing that. It’s not a happy ending—not by a long shot—but it leaves the door open a little longer.

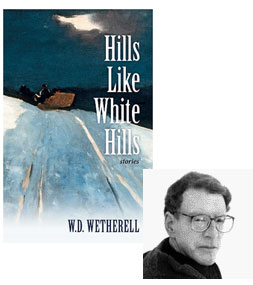

In the meantime, I have a few more SMU authors I wanted to share with you, starting with W.D. Wetherell and Hills Like White Hills. These aren’t always easy stories to read; in “The Master’s Hand,” for example, a recent widow finally lashes back at the years of emotional and physical abuse she suffered at her husband’s hands by taking it out on his dog. They are, however, powerful stories—and, in this essay, Wetherell reveals a youthful encounter with Daphne Du Maurier that set him on a long (and not always clear) path to a certain type of heightened literary realism.

Fate, the future, is fully capable of tapping a thirteen-year old’s shoulder, poking him or her in the ribs, pointing where to look, but somehow you wouldn’t expect this to happen in an eighth-grade English class in the last boring period of the day.

Mr. Goodwin, to his credit, tried hard to make our forty minutes with him bearable. He was an unconventional teacher—tweedy looking, reed thin, not afraid to voice his left-leaning opinions. Artsy, too. He took literature seriously, made sure we knew the names of contemporary writers like J. D. Salinger and Shirley Jackson, not just Washington Irving. His classroom was the hardest to find in the entire school, a real garret tucked away under the eaves; hidden there, he could teach his class any way he wanted.

Which involved, on the day fate struck, reading out loud to us Daphne du Maurier’s story “The Birds.” A few years later it would become famous via Hitchcock’s film, and du Maurier already had a big reputation as a best-selling Gothic novelist, especially for “Rebecca.”

Mr. Goodwin had an excellent reading voice—three sentences into the story, I was completely hooked. A young family living an isolated life in a remote part of Cornwall awake to find that the birds are acting very odd—the gulls swooping down as if to peck them, the robins beating their wings against the windows, the swallows darting down the chimney. Probing seems to be going on, testing, reconnaissance. During the day the birds become increasingly aggressive—windows are being smashed now, wounds inflicted, so the family has to barricade themselves inside. During a lull, the father goes for help to the next farm, and finds the farmer dead from bird wounds; gradually, with mounting horror, the family realizes that the birds are attacking not just their remote rural corner, but the rest of the country, the rest of the world.

It’s a wonderfully crafted story, absolutely convincing in its detail, and because it relies on imagination it is far more realistic and believable than Hitchcock’s movie with its clumsy, imagination-killing special effects. Du Maurier, through an instinct approaching genius, implicitly predicts the half-century of environmental doom we were in store for; mention is made of atomic bomb testing, but the actual reason for the birds’ rebellion is never explicitly addressed. Nature has savagely turned on us, it’s entirely our fault, and there’s nothing the story writer can do but perfectly delieate the working out of the horror that results.

It’s impossible to exaggerate the effect Mr. Goodwin’s reading had on me. I was already an avid reader, but mostly books about sports and war, and the fact that this story was “made up” and yet more believable, more vital than any non-fiction hit me very hard. For the first time I was aware that art was involved in the writing enterprise, that the author was working on me, creating with me, using my imagination just like she used her pen. I could hardly breathe by the time Mr. Goodwin finished. Some unconcious part of me decided that creating this kind of magic is what I someday wanted to do myself.

“The Birds,” with its realism pushed to the extreme by imagination, even pointed toward a certain storytelling strategy and approach, though it would be many years yet before I could begin struggling to work this out for myself. In the meantime, there was a baby step. Our assignment was to go home and write a story ourselves. A week later Mr. Goodwin, aka Mr. Fate, tapped me on the shoulder in a crowded hall.

“Wetherell? That story you wrote was wonderful. I’m giving you an A-plus cubed.”

No honor, no praise, no review, ever gratified me more.

24 May 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.