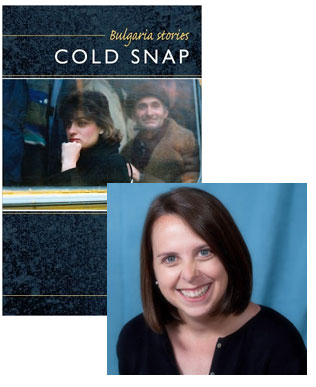

Cynthia Morrison Phoel and the Weight of the Past

I haven’t read Cold Snap yet, but after Tracy Winn’s endorsement yesterday, I’m really looking forward to it. I’m sure it will be great, because when it comes to short stories, I can count on SMU Press to deliver the goods—or rather, I could count on them, since it increasingly looks as if the university will follow through on its plans to shut down the press. So Cynthia Morrison Phoel may be one of the last authors they publish for a long while, and that’s a shame. In her essay, Cynthia pays tribute to Katherine Shonk, who has been seen at Beatrice before; somehow, I missed the news of Shonk’s debut novel, Happy Now?, coming out last month, so I’m going to have to track that down, too…

My forthcoming book, Cold Snap: Bulgaria Stories, takes an insider’s look at life in a small Bulgarian mountain town. I served in the Peace Corps in such a town; when I started to think about Bulgaria through my fiction, I found myself wanting to not just visit, but to re-enter people’s houses, minds, and hearts. To spend some time in their tippy stilettos or sturdy handmade loafers.

In her exquisite collection, The Red Passport, Katherine Shonk masters this insider’s stance, revealing post-Communist Russia with keen sensitivity. Re-reading these stories for the second or third time, one of the things that impressed me most was not the squeeze and chafe of her characters’ shoes so much as the persistent weight of the past on their stories.

This is as it should be. As Eastern European societies have struggled to come to terms with new realities, one way to make sense of the present is to see it in relation to the past. Shonk has the wisdom to know that this relationship is not uniform—that the relative value of past and present varies by character.

For some, the past is a consolation. In the devastating “My Mother’s Garden,” set near Chernobyl, Shonk writes, “The windows of the cottages are still framed with hand-carved woodwork, but the paint is bleached and flaking, and many of the panes are broken.” For an old woman who insists on living in her contaminated home, that hand-carved woodwork is beautiful—no matter the poison or peeling paint.

For others, the past obscures the present. In “The Wooden Village of Kizhi,” where truth about the past is kept hidden from Tanya, the story’s young protagonist, the past is painted over. “Each door was caked with yellow paint and topped with a rectangular window.” Tanya must peel back the layers of paint to arrive at the truth.

For still others, the past is everything. Or nothing at all. In the haunting “The Young People of Moscow,” the past comes to the foreground when an old poet, himself a relic of the past, beseeches some young cameramen to film his recital of one of his poems—a poem that praises a past life. Those short, glorious minutes in the glaring camera light took my breath away. But when the poem is finished, the young cameramen rush onward as though nothing has happened, “clapping each other on the back, the swirling fluff carrying them away, into the light.”

Over the last two weeks, as the literary world has rallied to keep SMU from shuttering its press, many have attested to the contribution the 73-year-old press has made to literature. In the here and now, I may be one of the 15 authors left stranded if the university has its way. But my book—which will be released in June—has yet to hit the stands. The overwhelming outpouring of support for the press’s future has everything to do with the wonderful books that have preceded mine—Tracy Winn’s Mrs. Somebody Somebody, Janet Peery’s Alligator Dance, and Adria Bernardi’s Openwork, to name a few.

For me, this past is a badge of honor.

20 May 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.