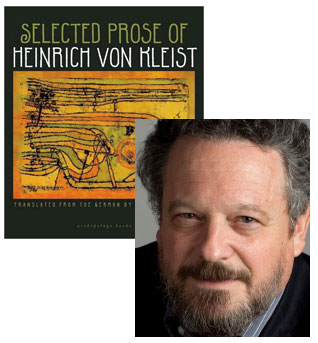

Peter Wortsman & the Box-Sentences of Heinrich von Kleist

I’m looking forward to Selected Prose of Heinrich von Kleist, one of the most recent titles from Archipelago Books, an independent press dedicated to international translation—and my eagerness is stoked even higher by this description by Kleist’s translator, Peter Wortsman, of the effort to render Kleist’s intricate prose style into just the right English.

Unlike the stalwart scribes that comprise the dominant strain of German letters, giants like Goethe, Mann and Brecht, one-man classics factories who spew wisdom in every breath and make library shelves buckle under the sheer weight of their words, Heinrich von Kleist belongs to a parallel literary strain, a trembling class of German writers whose ranks include playwrights Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz and Georg Büchner, enigmatic prose masters Franz Kafka and Robert Walser, and poet Paul Celan, to name a few. Their work—call it imperiled poetry, naked drama, or in Kleist’s case, self-destructing stories—puts its finger on the raw nerves of the real, sabotaging any pretense of certainty. Far from satisfying the reader’s need for assurance, Kleist’s stories still read today, 200 years after his death by suicide at the age of 34, like kamikaze attacks on the status quo.

Attempting to translate his prose is a rarefied, risky business akin to playing Russian roulette with a gold bullet, strolling over a half-frozen lake, or savoring blowfish sushi from which one is not altogether certain the chef has removed the deadly venom. The thrill of that lingering doubt naturally adds to the tingle, making every word all the more vital. Kleist played for keeps in everything he did, and every tempered sentence trembles with that sense of imminence transmuted from life into literature.

Having tackled other daunting stylistic challenges, including an English rendering of Robert Musil’s Posthumous Papers of a Living Author, now in its third edition (Eridanos, 1988; Penguin 20th-century Classics, 1993; Archipelago Books, 2006)—which, I am proud to note, was cited in the journal Modern Austrian Literature as “a kind of classic in itself”—I took on Kleist with mixed delight and trepidation. In the Musil translation, done more than 20 years ago, I had deemed it expedient to selectively subdivide his interminably long Teutonic sentences to appease an American predilection for syntactical simplicity. The result made Musil accessible to the contemporary English reader, while not, I hope, mutilating the essence. (Although a disgruntled Musil did appear to me in a dream, protesting what he called “schlamperte Arbeit,” a sloppy job.)

I have since come to the conviction that a sentence is a writer’s most intimate signature of self, that its structure follows the fault lines of the psyche that shaped it and should not, except in rare cases in which not to do so would obfuscate meaning, be tampered with in translation. This is particularly true of the Kleistian so-called “Schachtelsatz,” (box-sentence), a painstakingly constructed, airtight narrative nugget with a grain of truth at the core, around which he built his stories, layer upon layer, the way an oyster salivates pearls around a grain of sand. Disinclined to undue haste, the 19th German mindset took its sweet time in the telling, often getting tangled in subordinate clauses and occasionally losing its thread along the way, but Kleist always pulls it off with the surefootedness of a sleepwalker on an internalized tightrope.

Or to bend the metaphor, with his finger on the thread of Ariadne, Kleist took frequent strolls in a psychic labyrinth of his own confection, unafraid to meet, indeed courting the Minotaur within. He can no more be blamed for the convolutions of his narrative thread than can the Grimms’ Märchen hero Hans be blamed for strewing bread crumbs when he ran out of white pebbles. That was the only way out.

Let us briefly consider a single sentence close to the beginning of the novella “Michael Kohlhaas,” about a horse trader who, having been wronged by an arrogant Junker, resorts to violence to achieve justice:

“Er besaβ in einem Dorfe, das noch von ihm den Namen führt, einen Meierhof, auf welchen er sich durch sein Gewerbe ruhig ernährte; die Kinder, die ihm sein Weib schenkte, erzog er, in der Furcht Gottes, zur Arbeitsamkeit und Treue; nicht einer war unter seinen Nachbarn, der sich nicht seiner Wohltätigkeit, oder seiner Gerechtigkeit erfreut hätte; kurz, die Welt würde sein Andenken haben segnen müssen, wenn er in einer Tugend nicht ausgeschweift hätte.”

And here’s my English:

“In a village that still bears his name he owned a horse farm, on which he quietly earned a living in the practice of his trade; he raised the children his wife bore him in the fear of God, to be diligent and honest; there wasn’t a single one of his neighbors who did not benefit from his benevolence and fairness; in short, the world would have had to bless his memory had he not gone too far in one virtue.”

The narrative premise is all laid out here in a tight-knit web that the rest of the text will proceed to unravel. And though, in our 21st-century haste, we modern-day English speakers are no longer accustomed to taking in quite so much detail in a single gulp, it would have been unthinkable to chop it up, lest the sentence forfeit its oomph and wriggle in lame English like the segments of a severed earthworm feigning life.

My object throughout was not, I assure you, based on any nostalgia for longwindedness—I myself am a near fanatic of brevity—but rather, true to the spirit of the original, to ferry the reader to a parallel universe, and let him or her linger there a while. If I’ve succeeded in my task you might risk a spell of seasickness, but you won’t forget the journey.

3 February 2010 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.