Read This: Oishinbo

Over the New Year’s weekend, I plunged into four volumes of Viz’s translations of the Tetsu Kariya/Akira Hanasaki manga Oishinbo—which, rather than run through the 27-years-and-counting storyline, picks out individual chapters and arranges them thematically, with volumes devoted to subjects like Japanese cuisine, fish, sake, and pub food. The effect is somewhat disconcerting, because you’re frequently skipping over huge gaps in the characters’ relationships and struggling to fill in the pieces; imagine watching Happy Days for the first time out of sequence so that sometimes it’s about Richie and his pals, then it’s about Joanie and Chachi, and sometimes Arnold runs the diner and sometimes Al does, and Ted McGinley wanders in and out of view…

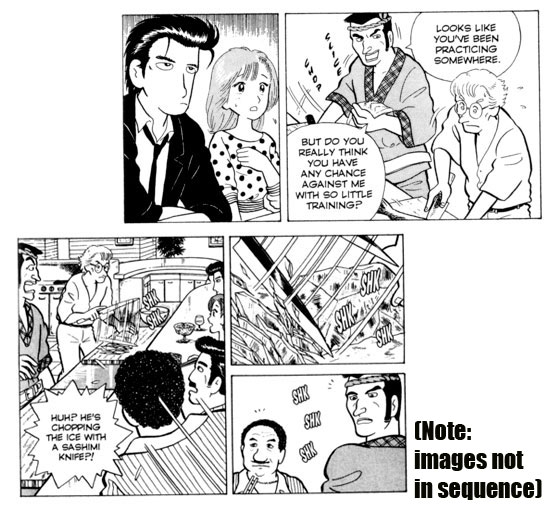

Still, this arrangement gets at the real heart of the popularity of Oishinbo, which is its obsession with Japanese food as a matter of honor and national cultural identity. Seriously: Kariya and Hanasaki once spent three chapters on a debate over the propriety of serving raw salmon, and six on every single thing that was wrong with Japan’s sake industry—imagine if Steve Ditko took all the passionate intensity of Mr. A and poured it into a comic book about cooking, and you’ve got a rough idea of what to expect. Speaking of intensity, the one core element of the narrative that does come through in the retelling is the feud between Yamaoka, the protagonist (he’s the one who looks vaguely bored up above), and his father, Kaibara.

9 January 2010 | read this |

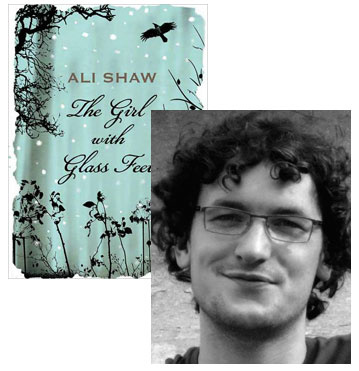

Ali Shaw and the Real-Life Glass Delusion

My airplane reading this week has been Ali Shaw’s debut novel, The Girl With Glass Feet, which is a contemporary fantasy written with such elegance that the literary crowd is already setting it aside for the “magic realism” camp. All kidding aside, it’s a wonderful story that ought to be embraced by fans of, let’s say, Charles de Lint and Aimee Bender alike, already up for Britain’s Costa Award (formerly the Whitbread) in the first novel category and sure to get plenty more recognition now that it’s finally out here in the States. In this essay, Shaw reveals how there’s actually a historical parallel to the curious condition of the woman at the center of his tale—but he never knew about it until after he’d finished writing.

Of all the bizarre notions and ideas that befuddled the heads of the medieval kings and queens of Europe, among the strangest must be the French king Charles VI’s conviction that his body was made from glass. This delusion saw the monarch dressing up in padded clothing, terrified to move for fear of smashing a limb, and it would be easy to dismiss as the unchecked imagination of a pampered royal were it not for the fact that Charles’s case was by no means unique. He was but the most high-profile sufferer of what would be retrospectively termed the glass delusion, a mental illness that could strike people down regardless of rank or social standing.

I came across the delusion not long after the UK publication of my novel about a girl who is turning, slowly but surely, into glass. Having spent a few years writing the book, trying all that time to imagine as vividly as possible what it might feel like for her, it was peculiar to discover that the victims of the glass delusion had been through something similar (in their minds at least) some five hundred years before. There are, of course, some obvious differences. Ida, the character in my book, really is turning into glass, whereas the sufferers of the glass delusion only thought that they were. And from what we can tell about those with the delusion, they didn’t think that their flesh and bones were transforming into glass but that their bodies had mysteriously transformed into fragile vessels: glass pitchers, beakers and flasks. These ‘glass men’ were diagnosed as melancholy, which back then was a far more severe assessment than that word would imply today. As melancholics, they were lumped together with those suffering from other fantastical delusions. Robert Burton listed some of them in 1621:

“Another thinks he is a nightingale, and therefore sings all the night long; another he is all glass, a pitcher, and will therefore let nobody come near him … one among the rest of a baker in Ferrara, that thought he was composed of butter, and durst not sit in the sun or come near the fire for fear of being melted.” (The Anatomy of Melancholy)

6 January 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.