That’s Really Scary, Boys and Girls

It’s been a few years since The Stewardess Is Flying the Plane came out, but I still get asked to talk about ’70s Hollywood every once in a while. Recently, I did an e-mail interview with Brian Solomon, the editor of The Vault of Horror, where we talked about how the changes to the business and the culture of American movies affected the horror genre. During our back-and-forth, I reaffirmed the awesomeness of The Exorcist (not that William Friedkin needs my help, but hey) and put in a good word for one of my favorite films in any genre from the decade, Larry Cohen’s God Told Me To.

It’s been a few years since The Stewardess Is Flying the Plane came out, but I still get asked to talk about ’70s Hollywood every once in a while. Recently, I did an e-mail interview with Brian Solomon, the editor of The Vault of Horror, where we talked about how the changes to the business and the culture of American movies affected the horror genre. During our back-and-forth, I reaffirmed the awesomeness of The Exorcist (not that William Friedkin needs my help, but hey) and put in a good word for one of my favorite films in any genre from the decade, Larry Cohen’s God Told Me To.

I also noted in passing that one of the biggest signs of the impact of 1970s horror films is the extent to which, it seems, every last one of them is getting remade, and in the days since I sent along my responses, I’ve been thinking of two films that fall into that category that I could have mentioned but didn’t. George Romero’s The Crazies is another one of my all-category favorites from the decade, a perfect time-capsule of the prevailing mood of the period that society was just barely holding it together and everything could degenerate into chaos without warning; a new version of that film is coming out next month. Then there’s Race with the Devil, the one where Warren Oates, Peter Fonda, Loretta Swit, and Lara Parker get chased around the South by devil worshippers—it’s unclear in the film whether they actually have any magical powers, although I suspect they don’t; as I said in Stewardess, though, it’s scary enough just to be chased across the South by guys wearing hoods. Apparently there’s a remake in the works and projected to come out some time next year. I’m not sure there’s a pressing need—the original was satisfactory in and of itself—but honestly I’ve felt that way about most of these remakes.

21 January 2010 | interviews |

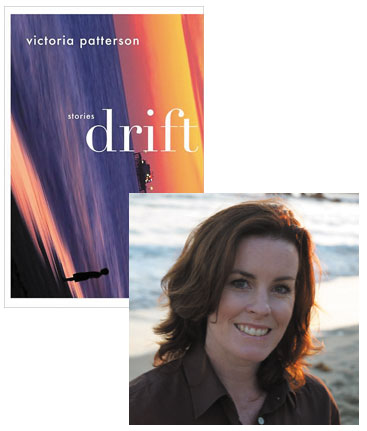

Victoria Patterson on Busch’s “Ralph the Duck”

When I started working for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt a few weeks ago, I reaffirmed my commitment to introducing you to books from other publishers; I didn’t want (and I’m sure you don’t want) Beatrice to become simply an extension of my day job. That said, every now and then there’s going to be an HMH title that I can’t help but write about, and today it’s Drift, one of three short story collections nominated for this year’s Story Prize. (And as long as we’re in full disclosure mode, I was a judge for that prize a few years back.) Patterson’s stories show us Newport Beach from the perspective of characters who live in its margins, people we might otherwise miss, blinded by the glare of Southern California’s coastal mystique. She’s already made some appearances in the literary blog world, including a guest essay at The Millions an an interview at The Elegant Variation, and in this essay she tells us about learning everything she could about one story’s author—having just missed the opportunity to tell him how much that story had meant to her.

In February 2006, I read Frederick Busch’s “Ralph the Duck” for the first time. “Ralph the Duck” is told through the first person voice of Jack, a 42-year old security guard at a private Northeastern college, taking advantage of the free classes offered to employees there, married to Fanny, an emergency room nurse, both of them mourning the death of their infant daughter. Tender and full of loss, moving through the murky region of despair, and imbued with a sense of high stakes, here was a story that played it straight, laid back the skin and cut to the bone. Later, I read that Antonya Nelson called it “a short story masterpiece.”

“I woke up at 5:25 because the dog was vomiting.” So begins Jack’s narration. The dog, we learn, “loved what made him sick.” Jack swears he can hear his wife blink because of “the damp slash of lash after I have made her weep.” Their marriage is suffering—faltering—from grief. They go to the movies and Jack “fell asleep, and I’m afraid I snored.” Jack’s voice is sad and funny, wise and knowing, aware of his shortcomings. When he sets out to save a local teenaged girl, he conflates it with the loss of his own child (“She better not die this time”).

20 January 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.