Victoria Patterson on Busch’s “Ralph the Duck”

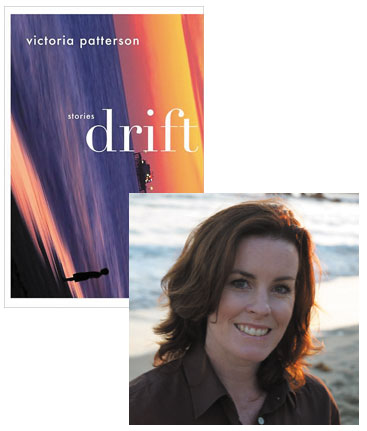

When I started working for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt a few weeks ago, I reaffirmed my commitment to introducing you to books from other publishers; I didn’t want (and I’m sure you don’t want) Beatrice to become simply an extension of my day job. That said, every now and then there’s going to be an HMH title that I can’t help but write about, and today it’s Drift, one of three short story collections nominated for this year’s Story Prize. (And as long as we’re in full disclosure mode, I was a judge for that prize a few years back.) Patterson’s stories show us Newport Beach from the perspective of characters who live in its margins, people we might otherwise miss, blinded by the glare of Southern California’s coastal mystique. She’s already made some appearances in the literary blog world, including a guest essay at The Millions an an interview at The Elegant Variation, and in this essay she tells us about learning everything she could about one story’s author—having just missed the opportunity to tell him how much that story had meant to her.

In February 2006, I read Frederick Busch’s “Ralph the Duck” for the first time. “Ralph the Duck” is told through the first person voice of Jack, a 42-year old security guard at a private Northeastern college, taking advantage of the free classes offered to employees there, married to Fanny, an emergency room nurse, both of them mourning the death of their infant daughter. Tender and full of loss, moving through the murky region of despair, and imbued with a sense of high stakes, here was a story that played it straight, laid back the skin and cut to the bone. Later, I read that Antonya Nelson called it “a short story masterpiece.”

“I woke up at 5:25 because the dog was vomiting.” So begins Jack’s narration. The dog, we learn, “loved what made him sick.” Jack swears he can hear his wife blink because of “the damp slash of lash after I have made her weep.” Their marriage is suffering—faltering—from grief. They go to the movies and Jack “fell asleep, and I’m afraid I snored.” Jack’s voice is sad and funny, wise and knowing, aware of his shortcomings. When he sets out to save a local teenaged girl, he conflates it with the loss of his own child (“She better not die this time”).

I appreciated the story’s seeming simplicity, and the way that Busch went to the core, not straying from emotional subject matter, as a lesser writer might, in fear of being considered overly sentimental or unsophisticated. Even the title poked fun at academic posturing, and declared itself as heartfelt, taken from an essay that Jack writes on Persuasion and Rhetoric for a professor who wears ironed dungarees and tells Jack, “You are not an unintelligent writer.” Written with Jack’s dead daughter fully in his mind, “Ralph the Duck” gets a D, but the essay and title provide an undercurrent of dignity and nobility to the story, to the characters, and a mysterious childlike pulsing of sadness and meaning.

I became somewhat fanatical about “Ralph the Duck”—about Frederick Busch—enough so that my husband encouraged me to write him a fan letter. He was a professor at Colgate University, and while trying to find his contact information, I discovered that he had died three days before. It really hit me, and I ended up mourning him, reading everything of his—everything about him—that I could find. I thought of writing his family, letting them know. It seemed to me that the obituaries weren’t doing him justice, that his writing wasn’t being properly recognized, even though he had said, “I’d like to be remembered as a really honest, minor writer of the 20th century.” And of his work: “I write about characters I want to matter more than my own theories and more than my own delights. The great problem is to face the fullest implications of one’s insights and fears—and to sustain the energy to make a usable shape from them. No: the great problem is to sit and write something worthy of the people on the page, and the good reader.”

I worried that ultimately my truest appreciation was in the reading, and how could I express that to his family? I had become so absorbed by his work, I didn’t know how to be properly demonstrative regarding it: too respectful to importune with my personal feelings. How to express that what he wrote was so valuable to a silent reader?

20 January 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.