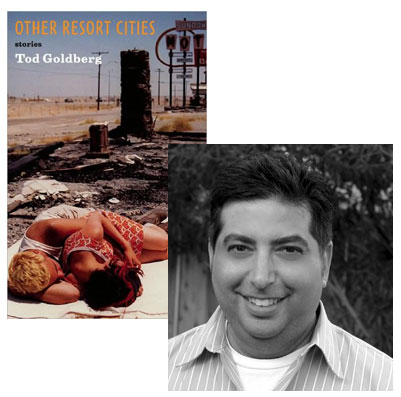

Tod Goldberg Revisits Rock Springs

Tod Goldberg is one of the finest literary mimics I know of; I swear, you read The End Game, one of his tie-in novels for the television series Burn Notice, and it’s like you’re hearing the lead character’s voice-over narration in your head. Mind you, I’m slightly biased: Tod’s a friend who’s shown up around these parts before, and I’ve spoken on panels he’s moderated. Despite the fact that I’m blatantly in the tank for Tod, though, you can trust me when I tell you his new short story collection, Other Resort Cities, is fantastic—you know what, you don’t even have to trust me, just go to Five Chapters and read “Rainmaker,” which is the last story in the collection, and you’ll see what I’m talking about, and then you’ll want to read “Mitzvah” and “Wills” and “Living Room” (the last of which is one of the niftiest of its kind since “The Swimmer”). Meanwhile, Tod’s going to tell you about the short story that set him on the path of writing about desperate people who’ve got some surprising moves left in them.

I’m of the general opinion that once you’re open to exploring new things, inevitably something will come along that you believe has fundamentally altered your life. I think this is true if you’re a fry cook and someone gives you a great new cooking oil, or if you’re a baseball player and someone tells you about how great human growth hormone is, or if you’re an aspiring writer—like I was once, before I became a cynical, angst-filled professional writer—and someone you trust realizes you’re reading (and writing) the wrong kind of stuff and introduces you to a work that just might be of interest to you. Maybe it doesn’t even matter what that work is exactly, only that it’s a work that person thinks you’ll respond to on some emotional level. If you’re open to being changed by a particular experience, odds are you’re going to be changed in one way or the other.

In my case specifically, that story was Richard Ford’s “Rock Springs”. To be accurate, though, I suppose it was the whole collection Rock Springs that caused me to wake up as a writer, but because “Rock Springs” is the first story in the collection—and I’d argue the best story Ford has written—the story served as my entry drug into a new way of thinking about writing and storytelling. The book was given to me by my Cal State Northridge writing professor Jack Lopez with the admonition that I stop writing until I finished the book.

That part was easy as he gave it to me over Christmas break in 1992 and I was a 21 year-old living in a fraternity house, which meant I was unlikely to write anything apart from beer-piss Greek letters on alley walls. But at the moment in my life I was ready to be changed, irrespective of the frat boy thing, because I was frankly tired of being a fuck up, of writing crap that my drinking-age ego wouldn’t allow me to admit was crap, but which professors like Jack kept telling me I could improve on if I just cared a little. Just a little.

So one night, after the beer ran out, I found myself with nothing better to do than read a book my professor thought might, you know, change my life. Thirty minutes later, I realized I’d been doing it all wrong.

It being writing.

It being reading.

It being understanding what it meant to be a writer vs. a person who writes.

Here was Earl: a felon on the run to a better life in a stolen Mercedes. Alongside him: his girlfriend Edna, his daughter Cheryl, his dog Little Duke. And in front of him:

“It felt like a whole new beginning for us, bad memories left behind and a new horizon to build on. I got so worked up, I had a tattoo done my arm that said FAMOUS TIMES, and Edna bought a Bailey hat with an Indian feather band and a little turquoise-and-silver bracelet for Cheryl, and we made love on the seat of the car in the Quality Court parking lot just as the sun was burning up on the Snake River, and everything seemed then like the end of the rainbow.”

That’s a simple and declarative paragraph about hope at first glance, but it’s also the story’s great tell, because many things feel like new beginnings when truly they’re the start of something awful, something that in the end you’ll look back on with regret because you knew in the very moment it was happening that it was only a feeling and not the truth itself. New beginnings are like most things you can look back on in your life and then give title to: You only recognize them after they’ve already been completed.

Of course I didn’t recognize any of those thoughts at 21 because what does anyone recognize at 21? But I certainly felt a shift in my perspective as a reader. Richard Ford was writing about a bad guy—a crook—who’d chosen a life of wrong choices and yet I still empathized with him, still wanted him to get to a place where there were no outstanding warrants on him, wanted him to get away with the long coil of his petty mistakes, to find that rainbow. And of course I knew it would all come crashing down on him because of those damn words “felt” and “seemed”—not unlike how, in the first lines of The Sportwriter, Ford uses the word “seemed” to similar effect—and yet, there I was, spellbound by the journey.

I re-read “Rock Springs” at least twice that first night and I’ve re-read it dozens of times since, not only because I teach it with regularity, but because it always inspires me creatively and reminds me emotionally of that sense I got all those years ago that I was in the presence of a real storyteller, of a writer who understood the vagaries of human emotion in a way I probably never would, but would try to figure out for as long as it took.

In the years since I’ve had similar revelatory experiences with other stories—”Passion” by Alice Munro, “The Prophet From Jupiter” by Tony Earley, “Aftermath” by Mary Yukari Waters, to name three—and with authors like Daniel Woodrell, Richard Russo and Robertson Davies, but it’s “Rock Springs” that reminds me of where I wanted to go and what I wanted to be and how long, how very long, that road would be.

23 December 2009 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.