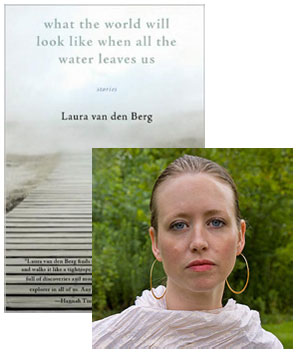

Laura van den Berg on Her First Love: “You’re Ugly, Too”

I first heard about Laura van den Berg two years ago, when she won the first Dzanc Prize for a project she had developed to teach creative writing in Massachusetts prisons. At the time, she was putting the final touches on the stories that form her debut collection, What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us, and, well, here we are. I’m loving these quirky stories and the women who are trying to make their way through a world that’s just like ours, only sometimes a fraction weirder, from the professional Bigfoot impersonator of “Where We Must Be” to the botanist looking for a rare flower on the shores of Loch Ness in “Inverness.” Van den Berg was kind enough to share her thoughts about one of her favorite stories in this short essay.

Perhaps it is because I’ve been reading the reviews of Lorrie Moore’s new novel, A Gate at the Stairs, or because I’ve been teaching her work in my classes this semester, but there are details from her brilliant short story “You’re Ugly, Too,” from the collection Like Life, that I just haven’t been able to get out of my head: that sad plastic baggie at the movie theater, Earl’s grotesque naked woman costume, the Illinois towns with names like “Oblong” and “Normal,” the earrings that stick out from the “sides of [Zoë’s] head like antennae.”

“You’re Ugly, Too has all the trademarks of a first-rate Lorrie Moore story—the dark wit, the well-observed characters, the arresting voice—but the reason this one remains my favorite of her oeuvre can, I think, be partially attributed to the way the story’s intense emotional power rises to the fore midway through the story like a jolt of electricity. For all its cleverness, the stakes for Zoë are deadly serious; her life, in respect to both her physical self and her psychic self, are at stake.

The scene I most love dissecting in my classes is the conversation between Zoë and Earl, a man she meets at her sister’s party in New York. The scene is phenomenal at rendering the tiny connections and disconnections, the coded bids for dominance, that can occur within a single conversation. And it is in this scene—which builds to a story Zoë tells about an acclaimed violinist who returns, disgraced, to her hometown and takes up with a local man who, after she commits the apparently unforgivable sin of not wanting to drink the night away with his buddies, informs her that “‘you may think you’re famous, but you’re not famous famous.’ Two famouses. ‘No one here’s ever heard of you,'” prompting the violinist to go home and shoot herself in the head—that the intensity of her rage surfaces. To tell this suicide story to Earl, a man who tries, at every turn, to keep the conversation on light and flirtatious ground, is the social equivalent of pulling a knife on him. This is the moment in which Zoë’s wit crumbles and her emotional wounds, her fury over all the injustices and humiliations, large and small, that life has thrown at her, burn brilliantly to the surface.

For me, this is the scene that makes the story, and I love it for a lot of reasons. It’s funny and volatile and it breaks my heart. This is a moment when Zoë drops the social niceties and sets herself, metaphorically speaking, on fire—a sad but also deeply compelling event to witness. It is also a human moment that I have always felt a pull toward, in my own work and in the work of others—that instant in which people on the edge decide to start burning it all down. But going beyond the story’s artistic merit, “You’re Ugly, Too” remains one of my favorite stories because it was the first work of fiction I really connected with.

Having not read much except the high school staples, I arrived at college, at the undergraduate fiction writing class I took on a whim, with no sense of what contemporary fiction looked like. “You’re Ugly, Too” was the first story we read for class and immediately I felt as though my world had been irrevocably tilted. Here in the pages of the impossibly thick anthology we had been required to purchase was an emotional reality, a way of seeing, that I recognized. Zoë and her troubles have lingered with me like a first love—perfect in its own strange way and completely unforgettable.

photo by Miriam Berkley

19 November 2009 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.