Jem: The Science Fiction Novel the Literary Establishment Embraced

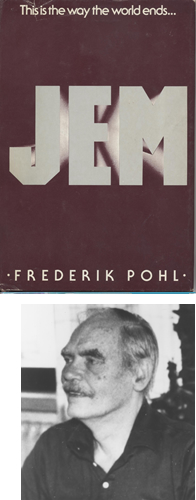

The National Book Foundation is celebrating the 60th anniversary of the National Book Awards by looking back at every one of its fiction winners, and the first contribution I’m making to the series is an appreciation of Frederick Pohl’s Jem, the first and only winner of an American Book Award (1980 was a strange year for the Foundation) for hardcover science fiction.

The National Book Foundation is celebrating the 60th anniversary of the National Book Awards by looking back at every one of its fiction winners, and the first contribution I’m making to the series is an appreciation of Frederick Pohl’s Jem, the first and only winner of an American Book Award (1980 was a strange year for the Foundation) for hardcover science fiction.

It’s only a few paragraphs, but I explain why the American Book Award for science fiction didn’t go along with the Hugo and Nebula commendations, and how certain aspects of Pohl’s novel find resonance with other authors from Charles McCarry and Ted Mooney to Jonathan Lethem and Junot Diaz. Unfortunately, it’s really hard to find Jem in the U.S., but if you put in the effort I’m pretty sure you won’t be disappointed.

13 August 2009 | read this |

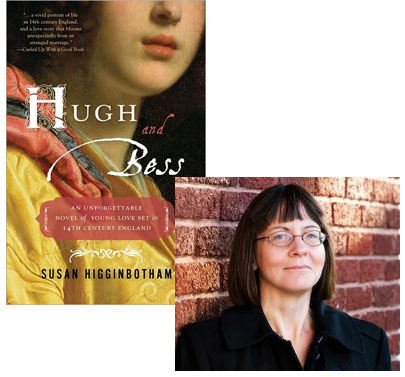

Susan Higginbotham: Discovering a Story in Edward II’s Court

I’m a sucker for historical fiction, so when I heard that Susan Higginbotham was making the rounds on the book-lovin’ Internet, introducing readers to her second novel, Hugh and Bess, my curiosity was piqued—not least of all because, based on what I’d gleaned from my preliminary readings, she’d dialed back the “epic” approach of her first novel, taking up a secondary character from that book and looking at him through a more intimate perspective. What, I wondered, led Higginbotham to that story? She was happy to explain.

When I first encountered Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II in graduate school, my professor told us, “Every English schoolboy knows how Edward II died.” Not being English or a schoolboy, I hadn’t heard of this king before; in fact, I would have been hard pressed to name any English kings before the Henrys in Shakespeare’s history plays. I most certainly couldn’t sort them out by Roman numeral. I read the play, and like my classmates duly shuddered when poor Edward meets his dreadful (and probably apocryphal) end. Then I forgot about him.

Over fifteen years, several moves, and two children later, I was surfing the Internet one night and came across an online version of the Marlowe play. I began reading a scene here and a scene there, and soon I simply gave in and re-read the whole play from start to finish. For some inexplicable reason, what I had found merely an interesting story back in the 1980’s had become a fascinating one to me now. I don’t know why, but I like to think it was simply because I was smarter in the 2000’s than I was in the 1980’s. Maybe it was because I no longer had those 1980’s shoulder pads wearing me down.

In any case, I am one of those people who feel compelled to read everything I can on a subject in which I become interested. (There’s probably something in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders about this; I’m better off not checking.) My quest for reading about all things Edward II soon took me to the local university library, and that’s where I discovered the tragic Despenser family, the most famous of whom were the father-and-son favorites of Edward II. From the thirteenth-century Hugh le Despenser, who fell in battle at Evesham beside Simon de Montfort, to the fifteenth-century Richard le Despenser, who died at age 18, each Despenser heir had died violently, young, or both.

My interest in the Despenser family had coincided with my newfound interest in fiction writing. As I began looking for information about the family, I discovered Eleanor de Clare, wife to Hugh le Despenser the younger and niece to Edward II. Her story, which took her on several revolutions of Fortune’s Wheel, begged to be told, and it turned into my first published novel, The Traitor’s Wife. (Along the way, I finally got all of my King Henrys and King Edwards straight. I still have trouble with the Georges.)

8 August 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.