Glen David Gold: Fame, Fame, Fame, Fame

Before we get started, Glen David Gold has embraced Futility, and he wants you to know all about it:

“My great-aunt Ingrid was Charlie Chaplin’s neighbor,” Glen David Gold explained to me as we met for iced tea last month before a bookstore appearance for Sunnyside, his first novel since the bestselling Carter Beats the Devil. (Yep, it’s been eight years!) “Family legend has it she wrote his autobiography—well, he did read his drafts to his neighbors and then take their suggestions.”

Sunnyside is, among other things, the story of how Charlie Chaplin weathered the blows to his public image during the First World War, and taking on Chaplin is a natural follow-up to writing about a character inspired by Harry Houdini, as Carter was. “Houdini was the first ‘most famous person in the world’ in the modern sense of the term,” Gold said. “He was famous because of his act, and Chaplin was his successor—but I knew there was a difference in the quality of their fame. I just wasn’t sure what it was at first…. A lot of his biographies are well-written, but they get to a certain point and they just throw their hands up.” He eventually realized why; it was a point in Chaplin’s life at which his fame had simply spiraled beyond his ability to shape it. “I grew up in Los Angeles,” Gold continued, “so I’ve seen fame happen to people. I’ve seen how gravity realigns around them when they enter the room. So what would it be like to be the first person that had happened to?”

Gold’s exploration of the relationship between the audience and the artist—between the spectacle and the spectator—led some early reviewers of Sunnyside to complain that the novel was too complicated, or required readers to connect too many dots themselves. Gold has taken the complaints in stride. “Some people complained Carter was too fun,” he observed. Citing Dos Passos as an example, he described a storytelling strategy that makes room for historical digressions: “You move off to the side and have faith that the forward momentum comes with the reader’s engagement in the world you’ve created.”

Another source of inspiration comes from John D. MacDonald, whose Travis McGee novels helped Gold realize the importance of giving readers a solid footing in early scenes so they’ll trust you when you begin to knock them off center as the story progresses. And when I mentioned that what I’d read of the novel so far reminded me of Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo in its playful treatment of history, Gold’s eyes lit up; he studied under Reed in his graduate creative writing program. “Ishmael was very playful,” he recalled. “but I also admire his ability to both critique and empathize simultaneously. He did not speak with contempt, even of the most contemptible characters… Writing was obviously to him one of the resaons to get out of bed.”

It doesn’t take much to see how fully Gold has inherited the attitude. I love Sunnyside, and I can’t wait to get back into the rest of it.

8 July 2009 | interviews |

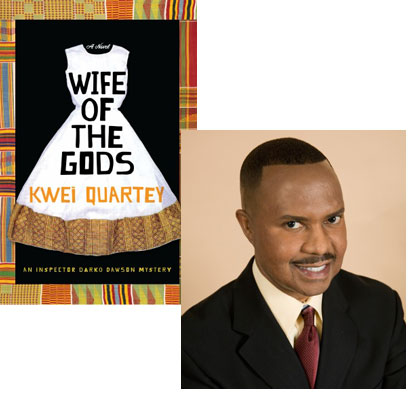

Kwei Quartey Re-Embraces the Ghana of His Youth

Wife of the Gods introduces a new contender in the international police procedural genre—Kwei Quartey. The novel is set in the West African nation of Ghana, shifting between the capital city and smaller villages several hours’ drive away, and incorporates local superstitions and controversial cultural traditions into the investigation of the death of a young medical student volunteering to teach the villagers about AIDS awareness. Quartey was born in Ghana but, because his mother was an American citizen, he had dual citizenship—a fact that came in handy when he became a “person of interest” to the military government after being caught putting up anti-government posters. He came back to the U.S., and eventually went into medical school; today he practices in the Los Angeles area, but he’s never abandoned his love of writing. I was curious to hear what it was like writing a mystery set in a land he hadn’t seen in many years, and he was kind enough to send the following essay by way of explanation.

I had been living in the United States many years when I began Wife of the Gods. Originally, I set the story in an imaginary West African land, but a literary agent wondered why I had not used Ghana for the setting. After all, I had once lived there. Ostensibly it was because I had been in the States for so long without returning to Ghana to visit that I wasn’t confident that I could portray the country accurately. On a deeper psychological level, though, I seemed more comfortable with a “Ghana-like” country than the real nation with which I had an emotional link. Was I, for some reason, skirting those emotions?

It then became a matter of re-embracing Ghana. When I finally did so, the writing became plainly more enriching. It was like taking a plunge in the pool and discovering that the water was just fine.

I’ve always had a scientific mind. As a boy growing up in Ghana, I was crisply confident that almost everything in life was of a biological, chemical, physical, psychological or medical nature. In my teens, I chose a science curriculum at school, the path that took me on to the study of medicine.

Outside the cocoon of my scientific convictions, there was an alternative world in Ghana. We sometimes heard about juju, which is a fetish or charm, or the magical powers attributed to such an object. At one point in Accra, Ghana’s capital, there was a lively rumor about a juju “going around” the city and making men impotent. Naturally, this was the stuff of nightmares for any believing human male. My amusement at this story of juju-induced impotence was tinged with disdain.

The comfortable bubble of my scientific world was similar to my family’s socioeconomic status. My brothers and I were the children of two lecturers at the University of Ghana, arguably an ivory tower where life was detached from the common man, woman and child. That was but one example of the inequalities we saw in Ghana. Of course, such contrasts also exist in developed countries, but in emerging nations the disparities, much starker, assault one’s sensibilities.

What does the novel’s title, Wife of the Gods, mean? How does a woman become a wife of the gods? In essence, how does one connect the physical, tangible world with a realm in which gods dwell? For some in Ghana, the answer would be that there is no need to join the two, as they already coexist. Case in point: In the novel, a young woman is murdered and protagonist Detective Darko Dawson soon discovers that some people believe the death is the work of a curse from the gods.

7 July 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.