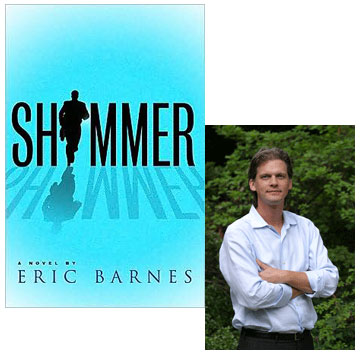

Eric Barnes Excels: The Spreadsheet That Launched a Novel

Robbie Case, the narrator of Shimmer, has a dilemma that, in this economic climate, should grab readers once he tips his hand at the end of the first chapter—he’s the CEO of a technology company worth billions upon billions of dollars, except there’s one small problem: the technology it manufactures doesn’t work, and Robbie knows that, one day, the elaborate house of cards he’s built to disguise that fact is going to collapse. In this essay, Eric Barnes explains how a real-life incident from his own corporate background led him down this narrative path…

It must have been 1998 when Bob, the owner and CEO, turned to me in a meeting at that big metal conference table in the corner office on the 2nd floor. “Eric,” he said slowly, staring at me, “do you think you can put together a spreadsheet?”

Bob was and is one of those deeply charismatic entrepreneurs, the kind of people who look at you and ask you to do something you can’t possibly do and to whom you inevitably find yourself saying, “Yes. Of course I can.”

Having put together many hundreds of spreadsheets since that day in 1998, Bob’s request does not now seem particularly grand. But, at the time, it was a big—even ridiculous—request, made when we were trying to raise money from investors to keep Bob’s company afloat.

First of all, our accounting software had essentially broken down. There was no simple way to find meaningful numbers about the company sales or expenses, let alone put them in a spreadsheet for potential investors.

The second problem was more serious: Even if there were numbers to pull from a functional accounting system, I had no understanding of finance. And no ability to create a spreadsheet. I was an arts major in charge of the production of city guides, business directories and Web sites. But Bob turned to me because the various financial people who’d already tried to put together a spreadsheet had all failed. I was good with computers, Bob figured. I knew how the company worked. The lack of financial understanding would just have to be overcome.

And then there was the third problem: The company was broke. I hadn’t known this until just a few months or weeks before that meeting in the conference room, even though I’d been at the company for many years. As part of the team pursuing investors, however, I’d been invited into the upper reaches of executive management. And a key step in the ritual of admission to the inner circle was the revelation of the fact that the company was, in effect, bankrupt.

20 July 2009 | guest authors |

J.C. Hallman, Lost In His Own Funhouse

J.C. Hallman uses a variety of metafictional starting points to set the stories in The Hospital for Bad Poets in motion. In the title story, for example, the critical treatment of an emerging poet is treated as if it were a medical diagnosis; “The History of Riddles” takes a couple preparing to entertain another couple in their home as an opportunity for philosophical reflection upon the ritualistic nature of games and social bonding. Then there’s “Double Entendre,” which is simultaneously an erotic story and a structural analysis of erotic stories—and in this essay, Hallman talks about the classic postmodern short story that inspired him to work within that particular framework.

If I think back through The Hospital for Bad Poets and compile a list of the authors and stories that I was more or less consciously emulating while I wrote, I pretty quickly wind up with the table of contents of an anthology I’d buy given the opportunity:

- “The Hunger Artist,” Franz Kafka

- “The Old Forest,” Peter Taylor

- “Dreams of a Robot Dancing Bee,” James Tate

- “The Swimmer” and “The Enormous Radio,” John Cheever

- “Star Food,” Ethan Canin

- “The Lottery,” Shirley Jackson

…and most important for this essay:

- “Lost in the Funhouse,” John Barth

Excavating one’s own literary heritage is both interesting and problematic. It’s interesting from a critical standpoint—assuming you find origins interesting—and it’s problematic for the same reason that civilizations in Italy are problematic: dig for bedrock and all you find beneath you are the folks who got there first, the ones that beat you to it. Plus, it’s not really supposed to work like that, is it? That is, at least when it comes to fiction, we expect a little imitation early in one’s career—the bush leagues, call it—but eventually you’re supposed to discover your “voice,” sail for terra incognita, volley forth like St. George to wherever there be dragons.

Except it’s never really been like that for me. And I’ve always been a bit jealous of poets in this regard.

19 July 2009 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.