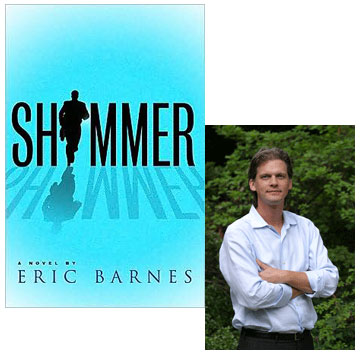

Eric Barnes Excels: The Spreadsheet That Launched a Novel

Robbie Case, the narrator of Shimmer, has a dilemma that, in this economic climate, should grab readers once he tips his hand at the end of the first chapter—he’s the CEO of a technology company worth billions upon billions of dollars, except there’s one small problem: the technology it manufactures doesn’t work, and Robbie knows that, one day, the elaborate house of cards he’s built to disguise that fact is going to collapse. In this essay, Eric Barnes explains how a real-life incident from his own corporate background led him down this narrative path…

It must have been 1998 when Bob, the owner and CEO, turned to me in a meeting at that big metal conference table in the corner office on the 2nd floor. “Eric,” he said slowly, staring at me, “do you think you can put together a spreadsheet?”

Bob was and is one of those deeply charismatic entrepreneurs, the kind of people who look at you and ask you to do something you can’t possibly do and to whom you inevitably find yourself saying, “Yes. Of course I can.”

Having put together many hundreds of spreadsheets since that day in 1998, Bob’s request does not now seem particularly grand. But, at the time, it was a big—even ridiculous—request, made when we were trying to raise money from investors to keep Bob’s company afloat.

First of all, our accounting software had essentially broken down. There was no simple way to find meaningful numbers about the company sales or expenses, let alone put them in a spreadsheet for potential investors.

The second problem was more serious: Even if there were numbers to pull from a functional accounting system, I had no understanding of finance. And no ability to create a spreadsheet. I was an arts major in charge of the production of city guides, business directories and Web sites. But Bob turned to me because the various financial people who’d already tried to put together a spreadsheet had all failed. I was good with computers, Bob figured. I knew how the company worked. The lack of financial understanding would just have to be overcome.

And then there was the third problem: The company was broke. I hadn’t known this until just a few months or weeks before that meeting in the conference room, even though I’d been at the company for many years. As part of the team pursuing investors, however, I’d been invited into the upper reaches of executive management. And a key step in the ritual of admission to the inner circle was the revelation of the fact that the company was, in effect, bankrupt.

So there I was, an arts major with no understanding of finance asked to put together a document that would at once honestly reflect our dire financial condition while simultaneously projecting a deeply promising future for both the company and, most importantly, the investors whose money we wanted.

And so I locked myself in my office for three weeks or more.

At the end of that period, I emerged with a document—a spreadsheet—some 500 pages long. I’d built a model of the company from the smallest expense to the largest. Every sheet of paper printed, every mile driven, every employee paid. I’d done the same with sales, identifying and delineating each item and service we sold, calculating the discounts, payment plans, and adjustments for uncollected bills.

All of it flowed into an ever-growing series of spreadsheets, each spreadsheet totaled, each total linked to another sheet in the series, all of it traced through the arcane formulas of Excel, where 2+2 equals =SUMIF(D$4:AI$4,$AJ$4,D12:AI12) and where the warning message “Error – Circular Reference” can ruin your whole day.

But I found that I liked building the spreadsheets. I liked the ability to break down the very complicated steps into simple formulas. No step in our production process was too small to skip. Everything we did at the company could be translated into a formula. The slightest change in the cost of paper clips would, in my model, effect our cash flow projection on a rolling, monthly basis.

There was a godly, omniscient aspect to all this. I walked into meetings with investors and could answer any question they had, could run numbers on any scenario they offered.

By night, back then, I was also writing. I’d been writing for years, having taken a day job only to pay the bills while writing fiction. The spreadsheets I created, the presentations we made to investors, the quandary of pitching the promise of a bankrupt company to strangers, all this started to spin in my mind. And I started to think about a company, and an office, and a person in charge of a life he’s created. Until one day at home at my computer I found the opening line. I’d started having dreams where I can fly.

20 July 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.