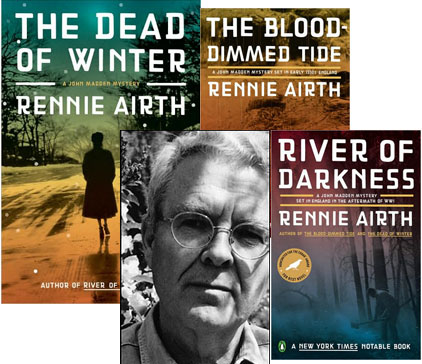

Rennie Airth: Murder Between the Wars

I recently read River of Darkness, a fantastic police procedural set in England, a few years after the First World War, pitting a serial killer against a Scotland Yard detective who is doubly haunted by his experiences in the trenches and the deaths of his loved ones in the influenza epidemic. It’s a carefully paced mystery that spends a great deal of time with its characters, drawing out 1920s British society through psychological detail. Rennie Airth has written two more novels about the detective, John Madden, each set a decade or so apart from the last. I’m looking forward to reading The Blood-Dimmed Tide and The Dead of Winter in turn, and I got to wondering how Airth came to develop this series.

The first impulse to embark on the Madden series came some years ago from an idle thought: How would the police have dealt with the problem posed by serial killers before they were recognized as such; before the very concept of forensic psychology had been developed? By chance, at about the same time, I was going through some old family albums and came across a scrapbook which my grandparents had kept in memory of their elder son who was killed in the First World War. Leafing through it I discovered something I hadn’t known before: The telegram they’d received advising them of his death had arrived in the same week as another telegram from the War Office informing them that their second son, my father, who like his brother was an officer in the British army, was missing. Fortunately he proved to have been captured, but I was struck by how appalling these twin blows must have seemed to them at the time.

From then on I began to read more about that terrible conflict and the deep scars it left on society. These two lines of thought came together and eventually led to the first of the Madden books, River of Darkness, in which the psychological damage inflicted on both protagonists, hunter and hunted, by their experiences in the trenches plays a major part in the story.

I decided early on, too, that I wouldn’t get trapped in a long series following the usual pattern of ‘another case for Inspector Madden.’ Rather, I wanted to place Madden and those around him, his family and colleagues at Scotland Yard, in the context of their time, and to see their lives develop quite apart from the mystery elements in each story. Hence the clear historical links which all three books have. The first, as I said, takes place in the shadow of the Great War; the second, The Blood-Dimmed Tide, against the rise of fascism in Germany and the looming threat of another war; while the third and most recent, The Dead of Winter, has the bombed-out ruins of London in the closing months of the Second World War as a backdrop.

To return to the question I started with—how the police might have hunted a serial killer in those days—I resolved early on to introduce a form of ‘profiling’ into my plots, while recognizing that this would have been resisted by diehard elements in the police force at the time, and for that purpose I created the character of a Viennese psychoanalyst, Dr. Franz Weiss, who appears in the first two books. A pupil of Freud’s, he is able to offer invaluable advice to the detectives investigating the series of murders, and being Jewish he also becomes a symbolic figure in the second of the stories as the Nazi party comes to power in Germany.

Getting the atmosphere right, avoiding anachronism, is always crucial in books set in historical, or semi-historical, eras, and I read a good deal about the periods I was dealing with. My research was superficial on the whole—what I was interested in was the flavour of the times, what people read, what they wore, what they ate, what they talked about—and for that purpose I was lucky enough to come across a book entitled The Long Week-End, jointly authored by Robert Graves and Alan Hodge, which provided a detailed picture of England between the wars. Almost more important was people’s behaviour, how they treated one another and how they spoke. I knew from the way my father behaved that it was a more formal, more polite time than our own and I tried to incorporate that into the books.

Mystery writers are often asked which they think is more important—plot or character—and I would unhesitatingly plump for the latter. Of course it’s necessary to have a good story: apart from anything else it prompts the reader to keep turning the pages. But there aren’t that many plots when you think about it—most of our tales are simply elaborations of a few basic themes, some found in the Bible, others handed down to us by the Greeks—while human nature is infinite in its variety. Accordingly I set out from the start to give my characters larger lives than the stories they happened to be caught up in and to watch them as the developed over a period of time which now spans two decades.

To sum up, I would say that the spur for all these stories grew from my fascination with the First World War and the society it left in its wake. It seems to me one of the great hinges of history and after it nothing was ever the same again.

21 July 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.