Kate Furnivall: What’s in a Name?

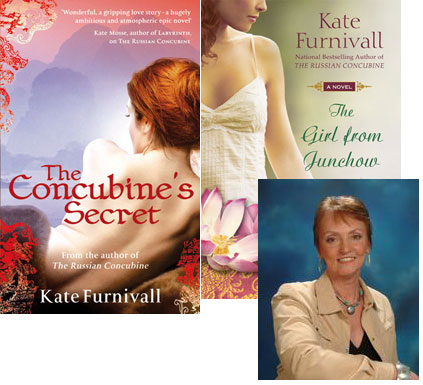

Nearly a year ago, I published a guest essay from Kate Furnivall about addressing her uncovered Russian ancestry through fiction. This summer, she returns to the world of The Russian Concubine with a new novel called The Girl from Junchow… except in the United Kingdom, where it’s known as The Concubine’s Secret. As the possibility of a new guest essay emerged, I found myself wondering about those two titles—so I asked if she’d be willing to explain how they came about.

Titles are magic keys. They open the door to a book. They are designed to give a sense of what lies between the covers but in such an intriguing way that they tempt the reader to pick the book off the shelf in the bookstore.

Question: What makes a good title? Answer: One that sells books.

This is the holy grail of both novelists and publishers. Ideally, any writer will tell you, it is preferable to have settled on a title before even starting to put pen to paper because it means you have worked out exactly what lies at the heart of your book, what your focus is as its author. It means that every day when you open up the file on your computer, it is there in front of you in large letters—the title of the book. Reminding you what it is about.

Wouldn’t it be nice to live in such an ideal world? But sadly we don’t. So titles do not always slot into the brain as conveniently as authors would wish. Think about the titles that have attracted acclaim. There are some great ones out there—For Whom The Bell Tolls and Gone With The Wind. And more recently of course the supremely simple The Da Vinci Code. I’d really like to know how convoluted was the process by which those titles were chosen.

An author can spend months trying to drum up the right title. I know. I’ve done it. As the days and months tick by while you’re writing the book, endless wakeful hours in bed are spent with your mind churning, trying out every different combination of words. Whether you’re mowing the lawn, cleaning your teeth or feeding the cat, your mind keeps tugging at the knotty problem. It can end up driving you mad. And that’s when—if you’ve any sense—you rope in your publisher and agent to help.

Then the lists begin. We email each other a bunch of title suggestions every few days. We scour the manuscript for ideas and phrases. We plague colleagues, friends and family, trying out titles on them. We’re getting desperate. Losing our sense of what suits the story and what doesn’t. We make long lists. We make short lists. But before we know it, the deadline for publicity has barged its way into the discussions and the marketing experts step in. Presented with a final list at a ‘titles meeting,’ they choose with a fine eye for the market.

Even when an author submits a manuscript with what he or she thinks is the perfect ready-made title, too often we choose from a position too close to our beloved brainchild. A publisher will often suggest very gently that it isn’t ‘quite right.’ The trouble is, I see their point of view. Yes, now they’ve pointed it out I see my title is perhaps too obscure, too tame, too long, too short, too misleading or just not leading anywhere.

Take my latest novel, for example. I was convinced I was on to a winner. The Russian Daughter was typed proudly in bold script on the front page of the manuscript when I submitted it. It says it all, I thought. That it takes place in Russia. The struggle of a daughter to find her father. Simple and to the point.

Nope. Both my US publisher, Berkley, and my UK publisher, Sphere, dismissed it—politely—as unusable. Too many ‘daughter’ books on the shelves already. So the dreaded lists began.

This is where an unforeseen problem arises: two different publishers in the English language, with two different preferences for the choice of title. Very quickly Berkley in the US settled on The Girl from Junchow. I liked it very much. It ties in neatly with my earlier book, The Russian Concubine, which took place in Junchow. Delighted, I passed it on to Sphere in the UK. The answer came back—very politely—No. They had decided to go with The Concubine’s Secret. Another excellent title, again with a strong echo of The Russian Concubine.

So here I am with two brilliant but different titles for the same book. It wouldn’t be a problem at all if it weren’t for the Internet. Both titles are available online, with no mention of the fact that they are the same book. So be warned!

But—I whisper this quietly—it’s looking good so far for the book I’m writing at the moment. My suggested title is producing contented murmurs from both sides of the Atlantic. So maybe I’m at last getting the hang of this title business, finding the magic key.

30 June 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.