Min Jin Lee: Discovering America’s Communities in Fiction

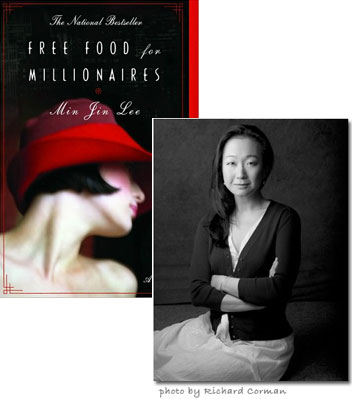

As part of the Beatrice tribute to Asian Heritage Month (see the end of this post for full details), Min Jin Lee was kind enough to let me reprint this essay, which appears in the paperback edition of her debut novel, Free Food for Millionaires.

My parents, sisters, and I immigrated to Queens, New York, in March of 1976. My family was sponsored by my uncle John, a computer programmer at IBM. I was seven years old—two years older than my main character, Casey. Also, like her, I grew up in Elmhurst in a blue-collar neighborhood. We lived in a series of shabby rented apartments for the first five years, and then my parents bought a small three-family house in Maspeth and rented out the other two floors while we lived on the second floor. I learned how to speak English and to read and write in the public schools of Elmhurst and Maspeth, Queens. My sisters and I were latchkey kids. Our summers were spent working in our parents’ wholesale jewelry store and hanging out at the Elmhurst Public Library.

I could not have articulated it in this way then, but my childhood was continually informed by immigration, class, race, and gender. This book features first-and second-generation immigrant characters, and therefore, I believe that it satisfies the definition of an American story because unlike any other country in this world, America has this generative quality due to its immigration policies and early colonial history. With the exception of Native Americans and descendants of slaves, in the United States everyone’s biography is ultimately connected to an immigrant’s journey.

I was a history major in college, and my senior essay was about the colonization of the eighteenth-century American mind. Quite a mouthful. My argument then was that original American colonists from England and the generations that followed felt profoundly inferior intellectually and culturally to Europeans and those back home in their motherland. That idea has affected how I see my own challenges in America as an immigrant. I am not legally colonized—far from it—but an immigrant is like an early colonist (a word currently out of favor), that is, a person who has come from somewhere else, who learns to adapt to her new land with all its attendant complexities with an overall wish to acquire new “territory.”

It is an interesting position to consider since I am venturing to make culture—my crayon drawings of what I see and notice—in the form of fiction. I can be critical of how this country works, but I also respect its ideals of rugged individualism, the Protestant work ethic, and the American entrepreneurial spirit. It is easy to criticize America, but from a global perspective this is an amazing country with tremendous openness. This comment has been made before, elsewhere, by many pundits, and I think it is worth considering: Many who criticize America would still prefer to live here rather than anywhere else. Carlos Buloson, the Filipino American author, titled his rich novel America Is in the Heart. To me —another immigrant from a later time—I, too, possess a complex America in my heart.

Having said that, if you honestly love any object or subject, you will ultimately need to admit to its flaws in the hopes of some idealized love. We recall America’s checkered backstory: the near-annihilation of Native Americans, enslavement of African Americans, Jim Crow legislation, gender inequality, immigration quotas for people from southern Europe, the Chinese Exclusion Act, the internment of Japanese Americans, America’s reluctance to entering World War II, Hiroshima, McCarthyism, Vietnam, and the list continues. And thus, we recognize with both shock and compassion how with every generation, America has transferred its set of insecurities and anxieties to the newcomer.

27 May 2009 | guest authors |

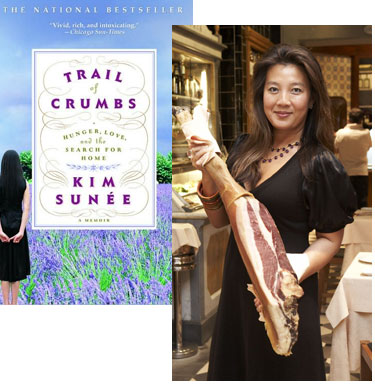

Kim Sunée Gets Her Dream Blurb

I first met Kim Sunée last year at the Pulpwood Queens book festival, where her memoir, Trail of Crumbs: Hunger, Love, and the Search for Home, was a big hit with the book club members of East Texas. She’s made a lot of other fans along the way—and in this essay, she tells how she found one of her first, at a crucial moment in the book’s path to publication.

I had turned in the final draft of my manuscript and was about to board a plane to Paris when my editor called informing me that the next step before my book could be published was acquiring blurbs. I felt sick to my stomach. Blurbs. I had heard from other first-time authors about how a line or two of praise from a famous author could make or break how a bookseller perceives you or if a reviewer will even take a second look at your advance copy among the hundreds she receives each week.

Most of my Paris trip was spent retesting recipes for the book by day and tossing at night trying to figure out who to ask and how to approach them. I didn’t know anyone famous enough to help me as a first-time author. My French writer friends didn’t understand the emphasis placed on a quote from another writer. “Doesn’t the book speak for itself?” they would ask while pouring me another glass of wine. How could I explain that in Amérique, we were obsessed with what others thought and that an advance copy without substantial blurbs was the sign of a book with a very short shelf life? I left Paris convinced that no one would blurb me.

A few days later, I went to Key West on assignment and, over drinks with the French chef, discovered that he had spent time in Michigan and Wisconsin. Jim Harrison’s name came up. I read Jim Harrison’s work, mainly his poetry, as a 15 year-old writing student in New Orleans. After ten years living and eating in France, and now that I was a food editor, I had come to also love Harrison’s The Raw and The Cooked: Adventures of a Roving Gourmand. It is one of those books I carry with me and give to people I hope will become lifelong friends. Offering up the book is a way of gauging how close we can really be. If someone truly doesn’t appreciate Harrison’s love of chicken thighs or isn’t struck by the last lines of “Heart Food in L.A.,” then I know it may be a rocky road ahead for our friendship.

26 May 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.