Ruth Padel, “Tropical Forest”

British poet Ruth Padel came to New York City recently, and I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to meet with her to talk about her latest book, Darwin: A Life in Poems. In this short video segment, she explains why, although she’s written about nature throughout her literary career, in both verse and memoir, this is the first time she’s really focused on her great-great-grandfather, Charles Darwin. Then, a poem about his wife, Emma.

Perhaps, after all, the angel was not wounded.

Kingdoms of his life rearranged themselves like cloud

after a storm. He felt washed open—an oyster

cleansed of grit. Marine metaphors flowed over him

as when he paced the deck of the little lone Beagle

at night. He felt loose, like a runaway cartwheel

bouncing from the heights into a valley

of violet oak trees. They stood

silent in the drawing-room, surprised.

She’d be engineer of all his happiness. Bees

shifted honey-bags up his spine. He was roses

burning alive, and she was the haze

above tropical forest plus the unfathomed riches

within. Like giving to a blind man eyes.

Tomorrow, I’ll share another short video with you, as well as the questions I asked after I put the camera down. In the meantime, you might want to read a NY Times profile by Charles McGrath, who took her to the Museum of Natural History.

20 April 2009 | poetry |

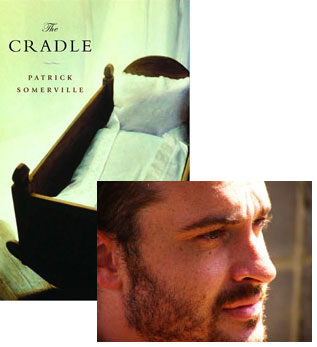

A Slumber Did Patrick Somerville Seal

I’d wanted to have Patrick Somerville bring his debut novel, The Cradle, to my reading series this spring, but when our schedules couldn’t mesh, I figured a guest appearance here on the website would be just the thing. We bounced some topics around, and then, it being National Poetry Month, I suggested Patrick tell us about one of his favorite poems—and he chose one that points to a formative period in his literary development.

Please do give The Cradle a look; if you want to find out more about it, Patrick recently uploaded a YouTube trailer where he searches for Wisconsin locations evocative of his fictional world. You can also read an all-new short story, “People Like Me,” at the online literary journal FiveChapters.com.

My now-threadbare Viking Portable Romantic Poets has been knocking around my bookshelf since 1998, my sophomore year of college—I had no working definition for the word “romantic†when I bought it (although the word did summon up a hazy image of a reclining pirate-Fabio), and when I showed up for the class it was for, my first upper-level English class, I tried to temper the skepticism I felt toward the forlorn-looking young man on the book’s cover with the very clear knowledge that I knew nothing about poetry. Over the course of the semester, however, I came to know the young Wordsworth and Coleridge of Lyrical Ballads to be far from the aliens I initially expected them to be; instead, they were surly, wandering, edgy intellectuals seeking out a new vocabulary for the human heart. I became very interested.

No poem reminds me more of that time in my life than Wordsworth’s “A slumber did my spirit seal.†Its ostensible simplicity, in both content and form, belies the many unsolvable questions left resonating beneath its opening lines: how is it, for example, that a “spirit†can “seal†a “slumberâ€, and why does the notion seem to make such immediate sense? And what kinds of fears remain once we stop talking about “human fearsâ€? Unclear. The mystery and nostalgia of that first stanza then give way to something far more powerful. Brief as they are, the final two lines summon the earth itself—not just the earth, but the machine of the earth, in time, tumbling in space, nature within. Alongside the absent “sheâ€, I find the power of the ending miraculous.

A slumber did my spirit seal;

I had no human fears:

She seemed a thing that could not feel

The touch of earthly years.No motion has she now, no force;

She neither hears nor sees;

Rolled round in earth’s diurnal course,

With rocks, and stones, and trees.

19 April 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.