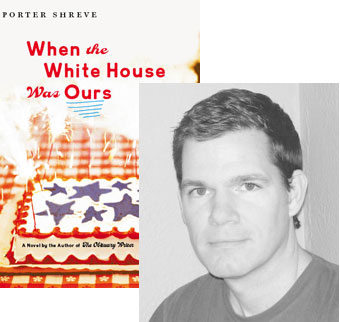

Porter Shreve Reclaims the White House (Our House, Too!)

I’m still in the opening chapters of Porter Shreve‘s new novel, When the White House Was Ours, but I’m totally loving it—even looking forward to subway rides where I know I can get in a solid chunk of reading time! In this essay, he explains how the novel is a mashup of his childhood experiences, with a whole lot of fictional twists added to make things even more interesting.

I was seven years old in 1973 when my parents received a grant to start an alternative school in Philadelphia. We lived in a cozy fieldstone cottage in Mount Airy, with my uncle Jeff and the remaining hippies from a small commune Jeff had formed in Colorado. My father, who had been the star of the University of Pennsylvania football team during its few promising years, was well liked around the city. But he couldn’t believe his good fortune when a near-stranger named Woodward, who owned many properties in North Philadelphia, handed him the keys to a vacant house a few blocks from ours, and said, as long as you’re starting a school, you’re going to need a schoolhouse. Rent-free for a year, renewable thereafter. With help from Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, my father named the school “Our House,” as in “Our House is a Very, Very, Very Fine House.” He advertised in the community papers, posted flyers around local schools, and by the end of summer nearly a hundred students had enrolled.

6 October 2008 | guest authors |

Linn Ullmann’s Blessed Child Reborn, in English

Linn Ullmann found the beginnings of her latest novel, A Blessed Child, in the image of a boy running through a landscape similar to that of Fårö, a small island off the coast of Sweden where she spent summers as a child. “Why is this boy running?” she asked herself, and then she linked that image to a popular theme from Norwegian folklore, stories about a king and his three daughters… Exploring the relationships between those two images, she says over tea, led her to the story.

Ullmann was born in Oslo, the daughter of Liv Ullmann and Ingmar Bergman, but she came to the United States as a teenager and stayed for college at NYU (“I’m still missing that essay on Conrad that was going to get me my master’s degree”), so her English is flawless, which led me to ask how active a role she plays in the translation of her novels from Norwegian. She works very closely with Sarah Death, “one of the best translators in Scandinavian literature,” emailing back and forth repeatedly to cover every aspect of the book, from the folksongs to the teenage slang of the 1970s, and to resolve distinctions between British and American English. Then, once an English manuscript had been presented to Knopf, Ullmann went over it again with her editor; “it was almost like writing the book all over again,” she says of the process.

Because her parents were often working on location, Ullmann spent a lot of time as a child with her maternal grandmother, who was a bookseller, and this fueled the young girl’s “ferocious appetite for reading.” Before pursuing her literary aspirations, however, Ullmann wanted to be a dancer, an ambition her father fully encouraged, building her a practice studio on Fårö. She became serious about writing while in college, and during her twenties was a literary critic for the Norwegian press. I ask her if the “crisis in book reviewing” has hit Scandinavia: “There’s still a lot of room for book reviews and articles—even in the tabloids,” she tells me. And, in “one of the wonderful sides of social democracy,” the National Library will order roughly 1,000 copies of any book published in Norway, to make sure Norwegians from one end of the country to the other have access to the same books. That frees publishers to select books for literary quality without purely commercial motivation, she says, “and publishers have the time to build an author… It’s generated a lot of good literature.”

Who’s a Norwegian writer Americans probably haven’t heard of yet but should know? Ullmann recommends Dag Solstad, who has had one book translated into English so far: Shyness and Dignity.

6 October 2008 | interviews |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.