Louis Bayard’s Secret History of Crime Fiction

In the last five years, since the publication of Mr. Timothy, Louis Bayard has become one of our leading authors of historical thrillers—but, he told me when we met in Washington, D.C., last month, “It’s not a niche I ever defined for myself. I just walked right into it.” After writing two contemporary gay romantic comedies in the 1990s, he had a literary itch that he simply couldn’t resist scratching: “All I know is that I wanted to write about Tiny Tim, and I wanted to do bad things to him.” After the success of that book, Bayard turned to one of crime fiction’s founding fathers, Edgar Allen Poe, for The Pale Blue Eye, and now, in The Black Tower, he has turned to Eugène François Vidocq, who rose to prominence as one of post-revolutionary France’s first criminal investigators.

“I was toiling through an idea for a novel about Franz Mesmer that wasn’t going where I wanted it to,” Bayard explained, when his editor at William Morrow, Marjorie Braman (who has since become the editor in chief at Henry Holt), suggested Vidocq, a name that Bayard had first encountered during the research for The Pale Blue Eye—he’d been curious that Vidocq was apparently so familiar to 19th-century readers that his name could be dropped without any explanation. “The more I learned about him, the more he intrigued me,” Bayard continued, until he decided Vidocq “should be put in the genre he helped create.”

20 October 2008 | interviews |

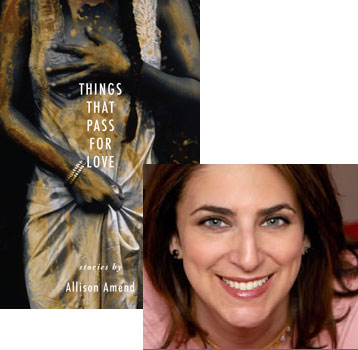

Allison Amend Stares Into “The Aleph”

I first met Allison Amend in the audience at a ceremony for the annual Story Prize, honoring the best short story collection published in America, introduced by a mutual friend. She mentioned she’d written some stories of her; I made a note to keep an eye out for them—and now I’m glad to be able to tell you that Things That Pass for Love is a marvelous collection that can turn from brutal realism with a dash of weirdness (“Dominion Over Every Erring Thing”) to disturbing portraits of emotional breakdown (“Carry the Water, Hustle the Hole”) with the flip of a page. In this essay, Allison celebrates a story which, now that I think of it, brings a disturbing psychological portrait into a story that starts out realistic and quickly gets weird…

There are stories you like and stories you don’t like, but it isn’t until you teach a story that you can really love or loathe it. I discovered this when teaching a course in Magical Realist Fiction, where Gabriel García Márquez’s “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” went on the nice-story-but-I-don’t-ever-need-to-read-this-again list and Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Aleph” was catapulted to my personal all-time top five canon.

The protagonist of “The Aleph” (who we will later learn, in an almost nonchalant afterthought, is named Borges too) mourns the death of his unrequited love Beatriz, forging a reluctant relationship with her cousin, Danieri. Both are writers; Danieri a hack: “He dealt in pointless analogies and in trivial scruples…. Danieri’s real work lay not in the poetry but in the invention of reasons why the poetry should be admired” while the reader assumes the first person narrator’s erudition indicates his superior literary skills. Danieri then shows Borges his secret muse, the Aleph, viewed through a hole in his basement stairs, “the only place on earth where all places are—seen from every angle, each standing clear, without any confusion or blending.”

Borges the author/narrator, unlike his self-aggrandizing frenemy Danieri, starts describing this experience by first claiming that it is out of the reach of description. ” And here begins my despair as a writer. All language is a set of symbols whose use among its speakers assumes a shared past. How, then, can I translate into words the limitless Aleph, which my floundering mind can scarcely encompass?”

13 October 2008 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.