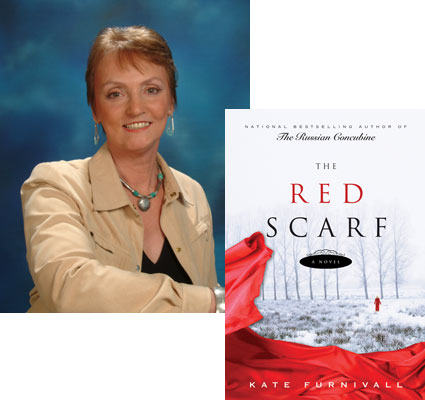

Kate Furnivall on the Road to Moscow

Authors turn to historical fiction for a variety of reasons—for Kate Furnivall, whose second novel, The Red Scarf, comes out this month, it’s all about coming to terms with the surprising revelations of her own family history, and understanding a cultural legacy that she didn’t even know about for most of her life.

Writing is therapy. There’s no question about it. Scratch any author and she or he will tell you it’s true. Writing The Russian Concubine and The Red Scarf helped me to accept who I am.

I was in my forties when I discovered I was part Russian, that my grandmother had been a White Russian in St Petersburg. It came as a shock. Her name was Valentina and she fled from the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution in 1917, down into China with her three-year-old daughter—my mother. Well, you could have knocked me down with a babushka.

So how do you deal with a discovery like that? When you learn you are not after all the pure English rose you’d always thought you were? It felt as if someone had pulled the rug out from under my feet and replaced it with a polovik. I had to rethink myself. But first I had to find out what being Russian meant. I had a preconceived notion, of course. Russia meant images of scary tanks strutting their stuff in Red Square, presidents who get drunk and topple over in public, and red-cheeked dolls that swallow each other like the whale and Jonah. Yes, I’d read my share of Tolstoy and Chekhov in years gone by, cried over “Lara’s Theme,” and even waded through Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archilpelago in the 1970s. But I was aware that the depth of my ignorance was greater than a Siberian oil well.

7 July 2008 | guest authors |

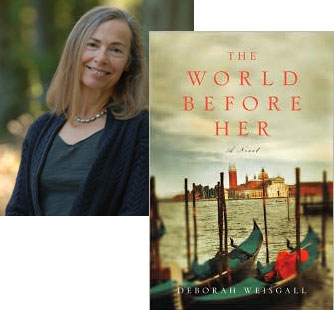

Deborah Weisgall Finds Modern Resonance in George Eliot

In The World Before Her, Deborah Weisgall contrasts the life of Marian Evans—known better to generations of readers as “George Eliot”—and a (fictional) contemporary sculptor, both of whom travel to Venice during moments where their personal and creative tensions have them at a crossroads. Why Eliot? Weisgall explains what she found in Eliot’s novels that spoke to her own literary concerns.

Of course I read George Eliot in high school. Tenth grade: Silas Marner, Adam Bede. The Mill on the Floss my senior year. These were harsh tales: passionate young women paid with their lives for their appetites—physical and emotional. Fates not so different from those that befell poor Emma Bovary or Anna Karenina. For a young and passionate woman trying to navigate the rapids of heart and mind, these stories were further examples of impossibility.

I was not wise enough to perceive that there was a difference—a difference of sympathy. George Eliot gave her women an ardor, an appetite, that went beyond the physical, a yearning that was emotional and intellectual—that struggled with moral issues as well as the strictures of society. It was not until I was a grownup that I understood how she was writing about love.

2 July 2008 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.