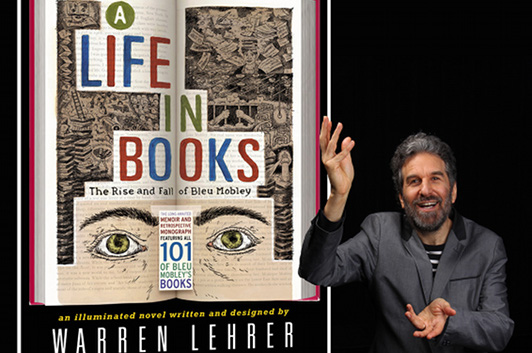

Warren Lehrer & the Bleu Mobley Oeuvre

photo and illustrations via Warren Lehrer

Warren Lehrer’s guest essay stems directly from a question I posed to him when I invited him to write about A Life in Books, a question that tackles the way it addresses the life of a fictional writer not just through that writer’s words, but his book jackets. “What drew you to telling a story through a mosaic of imaginary books?” I wanted to know. This was Lehrer’s response.

(By the way, all the artwork you’ll see below—and much more besides—is also part of a traveling exhibition that has often included a performance/lecture by Lehrer. Something to keep an eye out for…)

My previous five books were all non-fiction: four portrait books about eccentric Americans who each straddle the wobbly line between brilliance and madness, and Crossing the BLVD: Strangers, Neighbors, Aliens in a New America, written with Judith Sloan, which documents 79 new immigrants and refugees from all over the world who live in Queens.

After representing all these real people and their stories, I felt a need to work on something that gave me more room for invention, and allowed me to get at the interior world of characters. I started looking at all these book ideas I had scratched into notebooks, and drawers full of short stories and interior narratives I had written. And somehow, this peculiar, well-meaning if ethically challenged writer character emerged—Bleu Mobley—who was presently in prison looking back on his life and career.

Instead of just writing his story, I decided to combine his reluctant memoir with a retrospective monograph of all 101 of his books including their cover designs and ‘first edition’ catalogue copy. But the covers and catalogue descriptions didn’t satisfy my curiosity about my protagonist’s creative output, so I began writing book excerpts (that read like short stories). The excerpts started cluing me into aspects of Mobley’s life (people, scenarios, motivations) that I hadn’t anticipated. Some book titles that I thought came early or late in his career turned out to be middle period works, and vice versa. My Bleu Mobley life events/bibliographic timeline chart kept changing. As the puzzle of Bleu Mobley’s life revealed itself to me piece by piece, the relationship between an artist’s life and his or her work emerged as a major theme.

In the memoir part of A Life In Books, Mobley claims to have never written about himself, yet we discover him and the people he loves sleucing through all his books, however obliquely.

9 June 2014 | guest authors |

Sean Ennis: An Unsettling “Orientation”

photo: Claire Mischker

The Philadelphia of Sean Ennis’s Chase Us is a surreal, violent territory, one that the narrator navigates precariously from one story to the next. The collection isn’t so much a novel in stories, I think, as a series of variations on a theme; although the setting and the characters carry over from one story to the next, it doesn’t seem—at least initially—that a linear narrative carries over with them.) Once you’ve read a few of Ennis’s stories, you might be able to see what drew him to the Daniel Orozco story he’s written about in this guest essay…

I’ve always liked stories about work. Not only is it the place where most of us spend the majority of our time, but for a fiction writer, it seems like the ideal setting to create drama. Unless you’re very lucky, work is a place where you are often forced to interact with people you’d otherwise avoid.

Daniel Orozco’s “Orientation” takes the form of a dramatic monologue given by a middle manager introducing a new employee to the company. The specific work that this office engages in is never really mentioned, but we quickly get the sense that the audience for this speech has not exactly landed the ideal job.

In a lesser writer’s hands, it is easy to imagine this piece functioning as a one-note gag, riffing on the banal idea that office life is alienating and unfulfilling. No doubt, that idea is in Orozco’s story, but he’s mainly done with it after the first page. Instead, what follows is a list of an increasingly terrifying cast of characters who inhabit this particular office, brutally dissected by the narrator who speaks of the rules of the coffee pool and the sadomasochistic habits of his coworkers with an equally detached tone.

What I love and admire about this story is the way that both form and content are working in tandem. First, form. As a dramatic monologue, it places the reader in the position of the new hire being oriented, evaluating his/her new job for the first time. By the end it leaves the reader with a choice—decide to return for the second day on the job or run away screaming. I’m not suggesting that the story is so immersive that the reader actually forgets where they really stand—this isn’t a Disney ride. But it does mimic the question lots of people have about their job when they leave it for the day: will I come back tomorrow? While most great stories pose a question to the reader on some level, this seems much more explicit.

8 June 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.