My (Unexpected) Ender’s Game Problem

Lionsgate Film

My relationship with Ender’s Game is, as it is for many science fiction fans, complicated. I first read the novel as a teenager in the mid-1980s, and I remember identifying with Ender Wiggin the way subsequent generations of adolescents identify with Harry Potter—classic misunderstood, unappreciated boys who turn out to be humanity’s saviors. Over the years, though, it’s become harder to recommend the novel, or even its better sequel, Speaker for the Dead, to readers because of what we’ve learned about Orson Scott Card in the last 25 years.

I don’t intend to rehash the whole “love the art if not the artist” debate here. I reread Ender’s Game about a year ago and, though it didn’t impress me as much as it had back then, I could certainly see why I’d had that reaction. As good as the novel may be, though, and I realize that’s up for argument, I’m just uncomfortable with contributing to the ongoing success of a public figure whose politics I find abhorrent—and that includes encouraging other people to buy and read his work.

So I didn’t have any plans to see the Ender’s Game movie. Then, thanks to Card’s publisher, I was given the opportunity to see an advance screening and curiosity got the best of me. And, it turned out, the film is morally troubling for entirely different reasons than many of us, including myself, might have been expecting.

Note: There will be spoilers.

31 October 2013 | uncategorized |

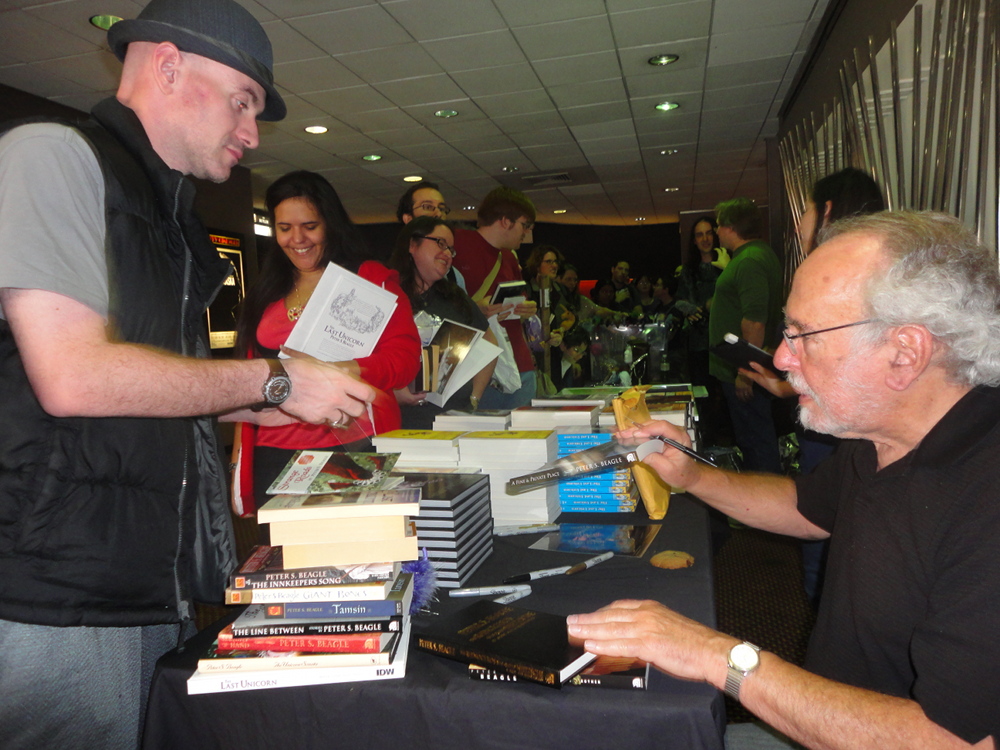

Last Unicorn (& Author) Back in Theaters

Peter S. Beagle was in his late twenties when his second novel, The Last Unicorn, was published in 1968. Fourteen years later, the fantasy story was adapted into an animated film—with an all-star cast including Mia Farrow and Christopher Lee—for which Beagle wrote the screenplay. It was, he recalled as he sat in the lobby of a Manhattan movie theater on a recent Saturday afternoon, the only input he had in its making. “People saw it and would congratulate me,” he said, “but it really didn’t have much to do with me.”

That feeling was exacerbated by contractual problems where, despite being promised percentages of both the film’s net profits and the gross on related merchandising, Beagle still wasn’t seeing any income beyond his initial screenwriting fee well into the 21st century. His business manager and publisher, Connor Cochran of Conlan Press, assisted in the negotiations—eight and a half years later, though, their efforts to resolve the situation amicably still hadn’t gotten anywhere. But then, as they began preparing to file a lawsuit in 2010, Scottish businessman Adam Crozier became the new CEO of ITV, the British media conglomerate that owned the company that had made the movie and Cochran saw an opportunity.

“Here was a fellow who had no reason to cover anyone’s ass,” he recalled; his efforts to reach out to Crozier eventually led to a meeting with the firm’s head of legal, Andrew Garard. When they met later that year, “half of the first meeting was Peter and Andrew geeking out about their favorite authors.” It didn’t take long for them to strike a deal aimed at reconciling all the various rights—Beagle had the gaming rights to the novel, for example, but they were virtually useless when separated from ITV’s rights to the likenesses of the film’s versions of the characters—to everyone’s profit.

13 October 2013 | uncategorized |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.