I Have Nothing to Say About Bookish

So Bookish.com finally launched in early 2013, only a year and a half or so behind its original target date, and various people have been weighing in with their judgments of how it turned out. I took a quick look, the night the site went live, but I didn’t really find anything that was both new to me and relevant to my interests, so as a “discovery engine” or whatever the popular term of art is these days (“recommendation matrix?”) I found it a bit of a wash. (Full disclosure: About a year ago, I had a meeting at Bookish, as part of a project I was working on for another company, and when I got there it turned out I knew a couple people who’d been hired on the editorial crew.)

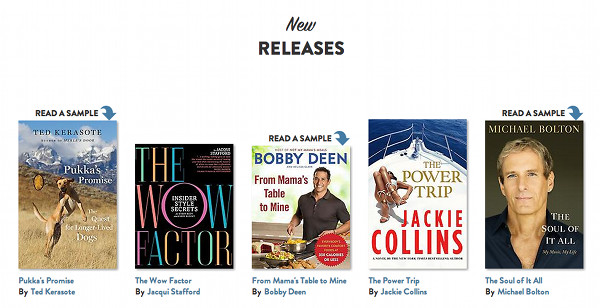

Here’s a recent spread of “new releases” Bookish was promoting on its homepage shortly after the launch. If you’re interested in fashion and beauty tips, Paula Deen’s offspring, the “mega-selling” Jackie Collins, or an inspirational memoir from Michael Bolton, then Bookish and you are going to get along just fine. (The other book is a dog memoir, and though dog memoirs aren’t at the top of my reading list these days, I’ve read other books by Ted Kerasote—helped promote one during my brief foray in corporate publishing, in fact—and he’s really good on the subject and a heck of a nice guy, to boot.)

If you’re interested in “literature,” though, or any kind of fiction, you’ll have to dig a little deeper—and, as Chad Post of Three Percent points out (at devastating length), for many active readers “this site is 100% redundant and unnecessary.” Specifically, it can be seen as an attempt to recreate everything that’s great about Goodreads only with the priorities of corporate publishing as its animating spirit. And, as Chad asks, “Why would I stop updating the GoodReads account I’ve been using for years to try and recreate it on Bookish?” There’s no point.

(Although, truth be told, I’ve been kind of lax about updating my Goodreads account. But we’ll get into that.)

Now, I’m extremely fortunate, in that I don’t need Bookish to help me find interesting books to read, because I already have people in my life that I trust to give me reading recommendations. If Sarah Wendell of Smart Bitches, Trashy Books, for example, suggests a novel like Vicki Essex’s Back to the Good Fortune Diner or Ellen Hartman’s The Long Shot, I can count on that book being top-notch contemporary romance. The flip side of this power dynamic, though, is that Bookish “needs” me, among other readers, to give it a bunch of book reviews and ratings to make its content more “robust.” (Actually, I suppose, readers like me are probably the last thing Bookish needs; Lord knows, if the corporate publishers behind Bookish dedicated themselves to servicing readers like me instead of the readers they do dedicate the majority of their resources to servicing, they wouldn’t be billion-dollar companies.)

As it happens, Mike Cane has already come up with excellent reasons not to share any information with Bookish, which dovetail neatly with my own main line of resistance—I’m tired of sites like Bookish making money off of my, if you’ll forgive the grandiosity, “literary expertise” when it could be generating capital for me. (See also: my declining rate of participation in Goodreads over the last year or so, as much as I enjoy the site.) I wrote about this back in 2011, and I’ve spent the last year coming up with some ideas and launching some projects of my own, like the Life Stories podcast and the enhanced Beatrice interviews for the iPad.

And that’s the real reason I don’t intend to engage meaningfully with Bookish as a consumer—not only does it not help me with the things it purports to help me with, the volunteer basis on which they’d like me to help them is a drain on my time and energy that I can’t afford. I do feel like I can do a lot to encourage people to discover some fantastic books and writers—but I’m developing my own agenda for that, and if corporate media outlets want to leverage my literary sensibilities, they can open their checkbooks.

7 February 2013 | theory |

Did the National Book Awards Need Fixing?

In recent years, the National Book Awards have come under a heavy amount of public criticism for the books they’ve proposed as the most outstanding in American letters in a given year. The criticism is almost exclusively aimed at the fiction selections, with the general thrust being that the writers who are appointed to the selection jury have some sort of elitist writerly criteria for picking precious, obscure books rather than books that ordinary people might have heard of. I’ve never gone in for that reasoning, and I’ve always value the perspective of the NBA juries—I may be fairly well-read by most statistical standards, but I know I’m barely skimming the surface of what’s available, so as far as I’m concerned calling my attention to excellent books I might have missed is a fine thing.

(In the interest of full disclosure, I should add that I’m friendly with several folks at the National Book Foundation as well as outspokenly sympathetic to their aims, to the point where I’ve contributed to their website.)

Now, there have been some changes in the NBA selection process, which in and of themselves are not so remarkable or unsettling. In fact, putting literary critics on the selection juries is actually a return to the way things used to be, as Foundation director Harold Augenbraum notes in the press release—in an ideal world, his prediction that “by enlarging the judging pool new and exciting voices will again deepen and enrich the process” is absolutely on target. Likewise, announcing preliminary ten-book “longlists” for each of the NBA categories a month before the traditional five-book finalist announcements, could well be an opportunity to expand the conversation around those books.

It’s when the rationale for these changes is elaborated to the media that I start to feel less enthusiastic; specifically, the remarks by Foundation board member Morgan Entrekin (who’s also the publisher of Grove/Atlantic and—again, full disclosure—somebody I’ve always respected and been delighted to run into as one does in the not-so-large world of mainstream book publishing) essentially conceding that the fiction shortlists have been “very eccentric” and affirming that the goal of a wider slate of candidates is to make the lists “a little more mainstream,” reducing the possibility that the award would go to what he seems to dismissively refer to as “a collection of stories from a university press.” (Two such books have actually been nominated in recent years, with Bonnie Jo Campbell’s American Salvage and Edith Pearlman’s Binocular Vision.) As far as he’s concerned, there’s plenty of prizes for books like that; the National Book Awards, he seems to suggest, should be about something bigger.

15 January 2013 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.